Key in a search term below to search our website.

Key in a search term below to search our website.

The story of how specimens make their way into a museum’s collection is often a peculiar one, and in the 19th century, it depended heavily on the relationships between individuals. Livingstone's rocks and minerals reveal the links between the famous explorer and other intellectuals of his time.

On arrival in Britain in 1856, returning after 16 years in central southern Africa, David Livingstone wasted no time in delivering his collection of geological specimens to the Museum of Practical Geology in London, where they were exhibited for the first time. The director of the Geological Survey and Museum was Roderick Impey Murchison, a supporter of Livingstone, to whom Livingstone had sent a series of geographical reports. These included the first east-west geological section of Africa, produced in 1855, a significant milestone for European scientists.

Murchison used Livingstone's geological specimens in conjunction with the first comprehensive map of South Africa prepared by Andrew Bain in 1852 (and published by the Geological Society of London in 1856) not only as evidence to support his own theory regarding the geological formation of the central southern Africa but also to illustrate the commercial mining and settlement potential of central southern Africa.

The specimens remained in London for over a year but were packed up again following correspondence with Dr George Wilson, director of the recently opened Industrial Museum of Scotland (now the National Museum of Scotland), a colleague from his days at University College London. In a letter dated 22 December 1857, Livingstone confirmed to Wilson that 'Sir R. Murchison thinks my geological specimens ought to go to you'.

Arrangements were made and on 12 April 1858, the collection of 77 specimens were duly recorded in the accession register along with the jaw of a hippopotamus and an elephant's tooth, also donated by Livingstone. The entries were based on the handwritten notes provided by Livingstone, with each specimen categorised according to classic geological subdivisions.

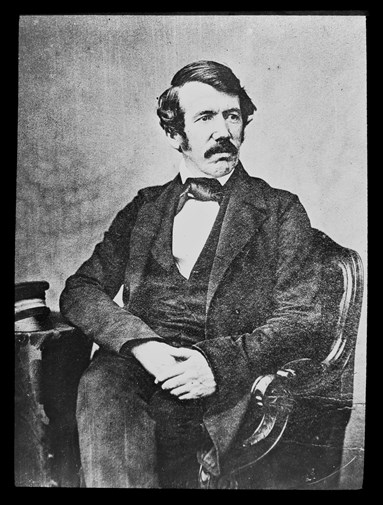

Above: Glass slide with David Livingstone's portrait.

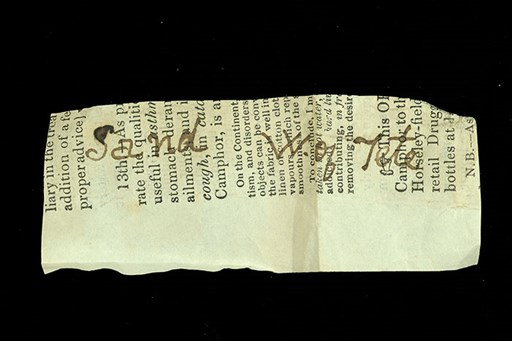

Above: Livingstone's handwritten note for one of the collected specimens. The explorer kept track of the place of origin of each item, and necessity made him tear one of the pages of his medical diaries to record from where the sand was collected.