Key in a search term below to search our website.

Key in a search term below to search our website.

The Cockcroft-Walton generator was developed at the University of Cambridge in the early 1930s to accomplish the first artificial splitting of the atom. These generators became an essential part of particle accelerators and other devices in research laboratories throughout the world.

Made by

John Cockroft (1897-1967) and Ernest Walton (1903-1995)

Made from

Metal

Maximum energy

1.0 MeV (mega electron volts)

Acquired

Gifted by the University of Edinburgh

Museum reference

On display

Grand Gallery, Level 1, National Museum of Scotland

Did you know?

By 1958 there were eight Cockcroft-Walton generators in the UK: six in universities and two at the Atomic Energy Research Establishment.

Matter is the stuff everything is made of. If we look around, all that we see or touch, or even the air we breathe, is made of matter. We are made of matter too. Matter is made up of tiny particles called atoms and molecules and it is normally found as solid liquid, or gas.

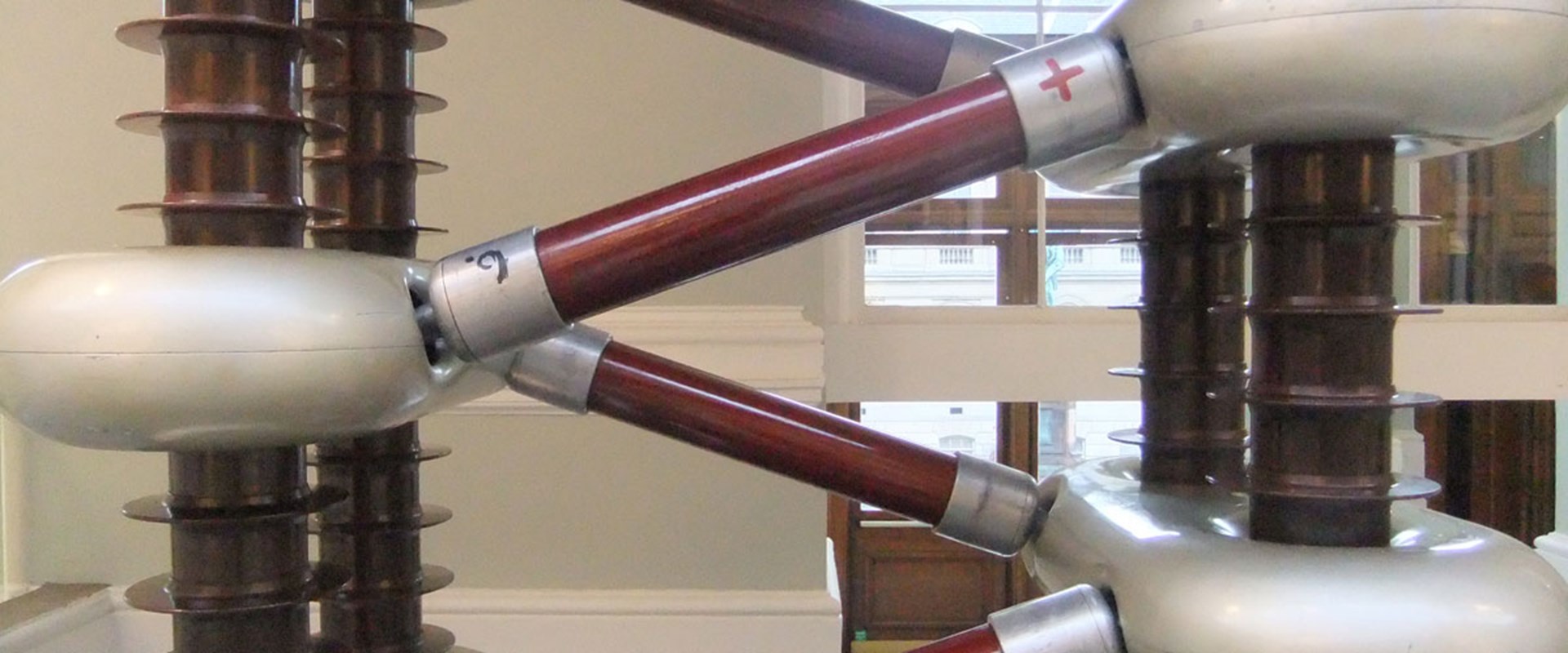

Above: The Cockcroft-Walton generator in the Grand Gallery at the National Museum of Scotland.

Scientists had been theorising for some time about what atoms were like and how they behaved. Particle physics and nuclear science are the areas of science that looks at the matter that everything is made of. Experiments to investigate atoms and subatomic particles require huge pieces of apparatus to generate the high voltages needed.

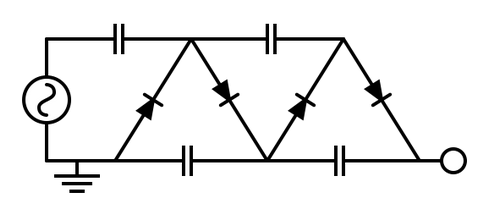

The growth of this experimental apparatus started in 1930, when John Cockcroft and Ernest Walton developed a voltage-multiplying circuit that used capacitors (components used to store energy) to produce high voltage direct current (DC) from a much lower alternating current (AC). They erected a column of rectifier diodes (which allow the electrical current to move forwards but prevent it from moving back again) and capacitors to produce a DC voltage four times greater than the AC voltage.

Above: A circuit diagram for a Cockcroft-Walton generator.

On 14 April 1932 Walton set up the voltage multiplier apparatus and bombarded lithium with high energy protons. Walton then crawled into the little observation cabin (made from a tea chest) set up under the apparatus and immediately saw scintillations on the fluorescent screen. This told him that the reaction was giving off alpha-particles: they had succeeded in splitting the atom.

Cockcroft and Walton's research was published later that month in Nature, detailing how they had achieved this momentous scientific breakthrough. The Cockcroft-Walton generators, as they became known, became an essential component of particle accelerators in research establishments throughout the world.

This is only one section of an accelerator used at the University of Edinburgh for nuclear physics research from the 1950s. You can find out more about its conservation and its display installation in the Grand Gallery here.

Smaller versions of this circuit were used to provide the high voltage needed by cathode ray tube televisions.

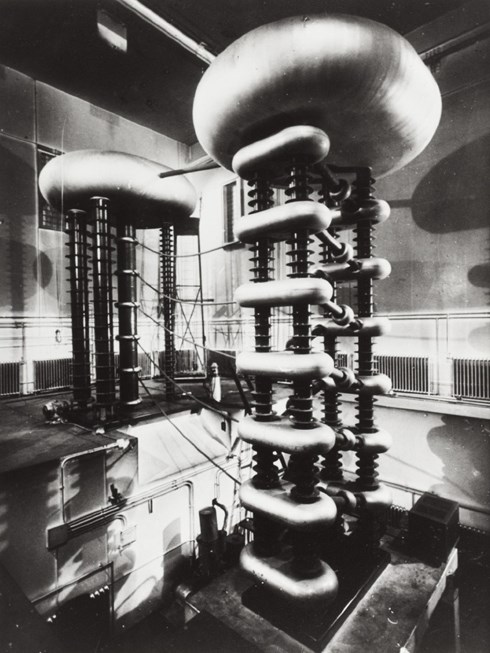

Above: The Cockcroft-Walton generator in use at the University of Edinburgh.

Most particle accelerators today have replaced their Cockcroft-Walton generators with more efficient radio-frequency quadrupole systems. They are much smaller and have fewer parts to maintain and replace over a lifetime. Modern particle accelerators, such as the one at CERN in Switzerland, can be many kilometres long. A Cockcroft-Walton generator was used at CERN in past decades and can now been seen on display at their visitor centre.

Above: Cockcroft-Walton generator on display at CERN, Switzerland.