Key in a search term below to search our website.

Key in a search term below to search our website.

Learn how malaria affects millions of people around the world each year and what methods are being used to tackle this deadly disease.

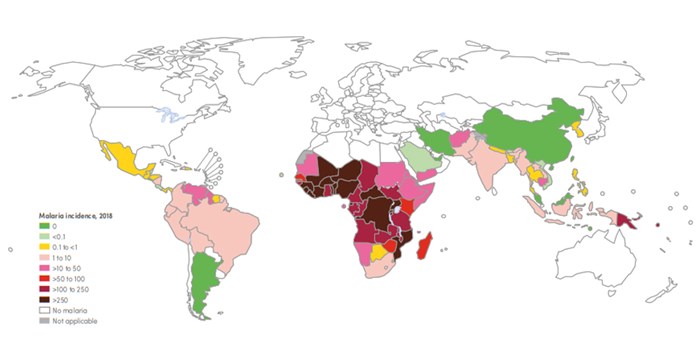

Map of malaria case incidence rate (cases per 1000 population at risk) by country, World Malaria Report 2019, World Health Organization.

The Plasmodium parasite uses female mosquitos to infect people with the malaria disease by biting them.

Female malaria mosquito blood-feeding © Sinclair Stammers/Reece

Disease |

Vector |

Parasite |

| Malaria | A female mosquito is a vector which delivers infects a human by biting them. | The Plasmodium parasite uses female mosquitos to infect. |

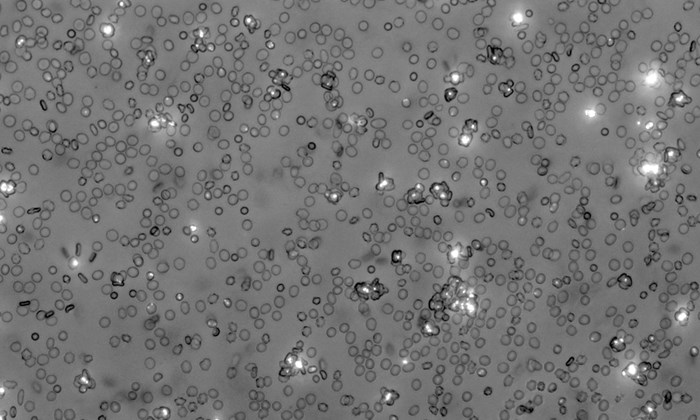

Malaria parasites (stained white) live inside red blood cells and can cause the formation of cell clusters called rosettes, seen here in a laboratory culture. Image from Professor Alex Rowe’s lab, University of Edinburgh.

Where:

90% of malaria cases are in sub-Saharan Africa

Symptoms:

Fever, headaches and chills appear 10-15 days after the infectious bite

Parasite:

Plasmodium Parasite burrows into liver and attacks the immune system

Challenge:

Left untreated, malaria can be fatal

Deaths:

400,000 people die each year

Cases:

There were 228 million cases worldwide in 2018

In 1897, Ronald Ross dissected mosquitos under a microscope and saw the malaria parasites developing. Before this people believed malaria was caused by diet or bad air, not through the bites of insects. In 1902, Ronald Ross was awarded the Nobel Prize for Medicine for his discovery of the malaria parasite Plasmodium.

Sir Ronald Ross, C.S. Sherrington, and R.W. Boyce in a laboratory at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine. Gouache by W.T. Maud, 1899. Credit: Wellcome Collection. CC BY

A study of over 650 samples of gorilla poo transformed scientific understanding of the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Professor Paul Sharp, from the University of Edinburgh, was part of an international team which proved that the parasite jumped to humans from gorillas and not from chimpanzees as was previously thought.

Gorilla poo on display in Parasites exhibition.

Professor Sarah Reece and her research team at the University of Edinburgh continue to try to understand how the malaria parasite evolves and they look for ways to beat the new strains of the disease.

One of their recent projects explores how parasites cope with attack from antimalarial drugs. By revealing what decisions parasites make, what information they use, and how their strategies maximise fitness, their research team can find weak points to exploit and help cure or prevent malaria.

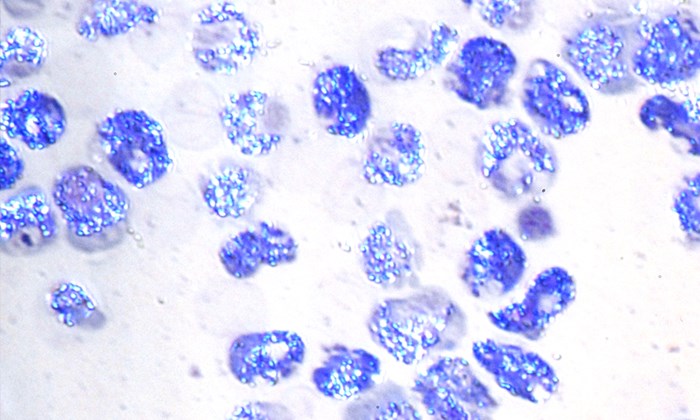

Plasmodium parasite in cells. Malaria parasites are the light blue dots in the dark purple cells.

A serious challenge in the treatment of malaria is spotting it in people who don't have any visible symptoms. They way to tackle this is with lots of field testing.

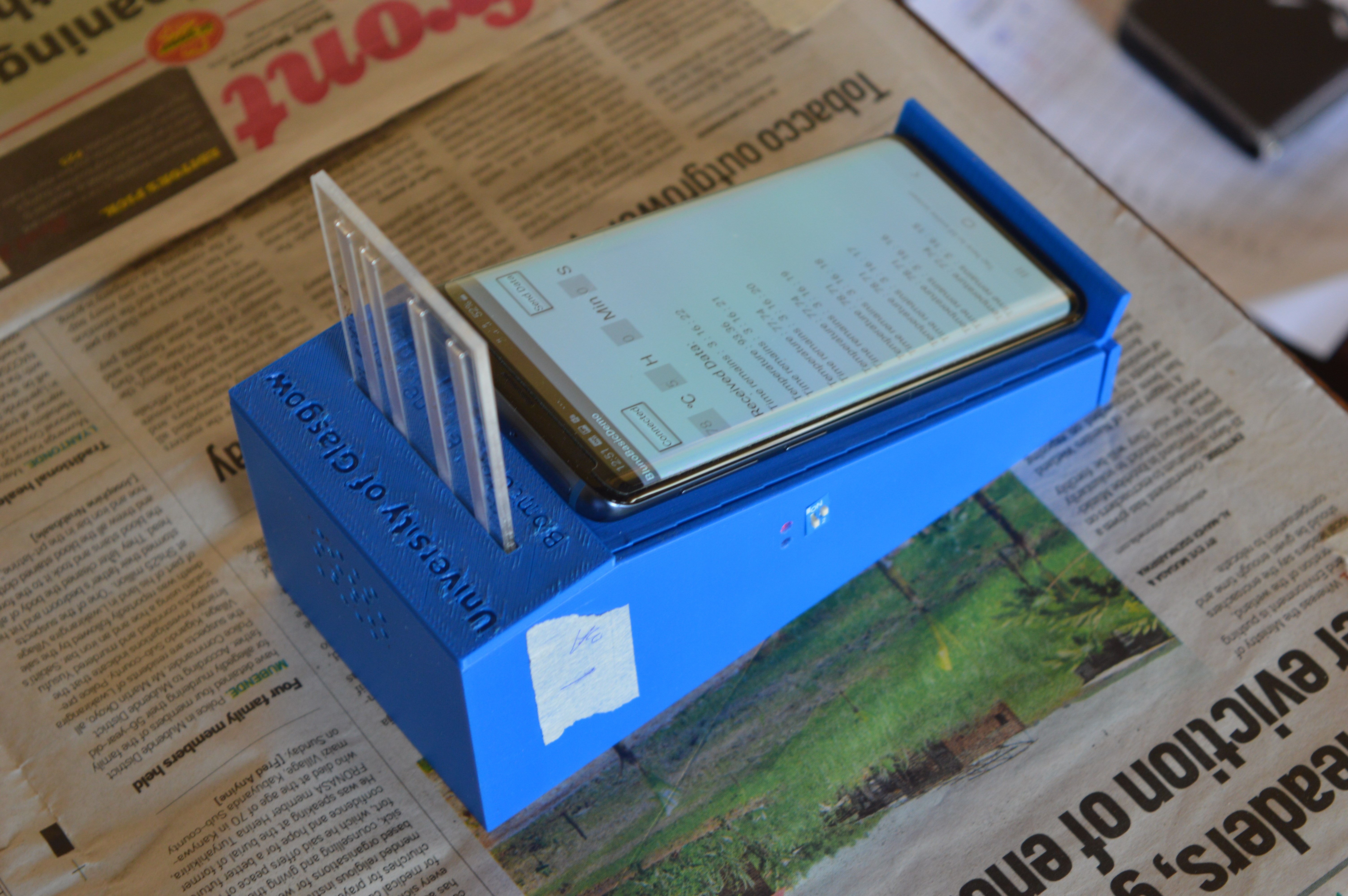

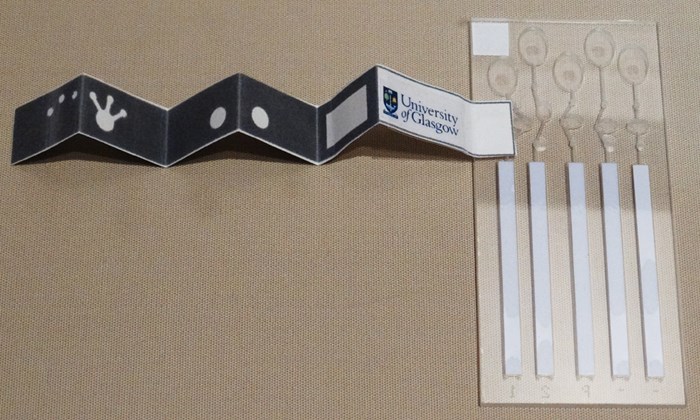

Diagnostic testing kit in action © Jon Cooper's Lab, University of Glasgow

There is a prototype test for malaria, made at the University of Glasgow, that may offer a simple, reliable alternative to complicated lengthy lab work.

It's cheap, 98% accurate and takes less than an hour. The test uses waxed paper to extract DNA from blood samples that are then analysed by the plastic chip. Currently undergoing field trails in Uganda.

Prototype Origami test © Jon Cooper's Lab, University of Glasgow

In Malawi, a project to distribute mosquito nets to prevent malaria had unexpected results. Without community consultation or supporting information, local people sewed the nets together to fish the local lake. The fine mesh trapped small fish that would have escaped traditional nets. The lake was overfished and water snails – the vector for the schistosomiasis parasite – flourished. This resulted in an outbreak of schistosomiasis and no decrease in malaria cases.

Mosquito net in packaging

Mosquito net in packaging

There are two types of medicines for malaria, those that prevent the parasite from causing disease and those that treat you once you have been infected by the malaria parasite.

Preventative treatments, or antimalarials, can reduce your chance of getting malaria by 90%. There are lots of different antimalaria medicines, some are more expensive than others. Find out more on the NHS website

If you have already been infected by the malaria parasite you need a medicine that can eliminate the parasite fully from your blood. Some of the medicines you can take to prevent malaria can also be taken to treat malaria. Treatment for malaria depends on the type of malaria parasite which has gotten you ill. Find out more on the World Health Organisation website.

Female malaria mosquito blood feeding © Sinclair Stammers/Reece

These resources were produced as part of the interactive exhibition, Parasites: Battle for Survival which ran at the National Museum of Scotland from 6 December 2019 to 19 April 2020.

School children exploring Parasites exhibition © Neil Hannah

Header Image: Eggs of the malaria mosquito.