The secrets of the Fettercairn Jewel

News Story

Find our more about this rare jewelled and enamelled locket, and how it could shed new light on the Scottish Renaissance.

Made from gold, enamel, and almandine garnet, the Fettercairn Jewel is an exceptionally rare Renaissance pendant locket.

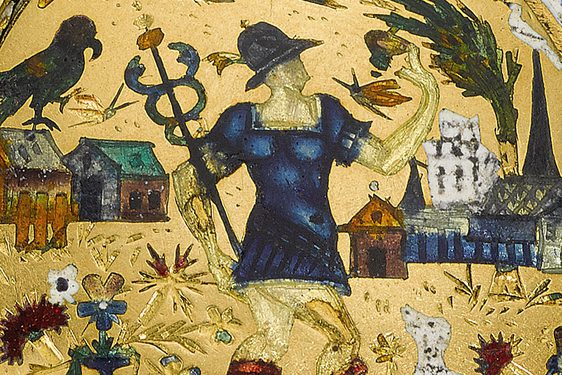

It is estimated to date from c.1560-80, and while possibly Scottish, its maker is unconfirmed. The jewel is oval, with a fastening at the top to hold a gold ring, and, at the bottom, a smaller ring, that was originally a catch to hold the case shut. The case opens and would probably have contained a miniature portrait on vellum or ivory or some other personal memento. It would have been worn as a pendant on a chain or pinned to clothing, and it probably had a pearl or precious stone hanging beneath it. An elaborate scene in enamel is featured on the back.

The Fettercairn Jewel is one of a very small number of Renaissance jewels to have survived in the British Isles. Jewellery from such an early date has a very low survival rate, due to the historic recycling of precious stones and materials. This makes the survival of the Fettercairn Jewel remarkable.

The short video below will tell you more about the importance of the jewel, how the messages contained within the locket can be decoded, and how curators at the Museum have researched and cared for this extraordinary object.

The Fettercairn Jewel (museum reference X.2017.45) is on display in the Kingdom of the Scots gallery, near to the Penicuik Jewels, which are associated with Mary, Queen of Scots.

Acquired with support from the Art Fund and Heritage Lottery Fund.