Childbirth

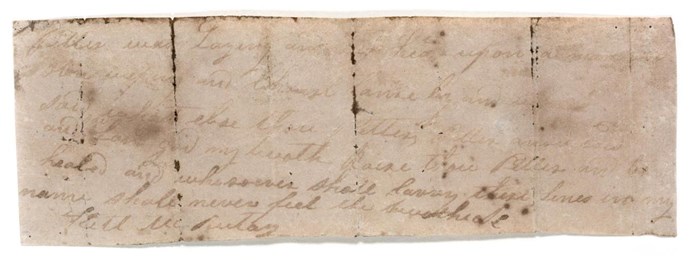

This charm, given to the museum in 1898, was made from a seed of Ipomoea Tuberosa from the tropical tree Caesalpinia bonduc after it was carried by sea to Colonsay, Argyll. It has been mounted for suspension and engraved with cognisance (heraldry) and the motto of Macneil of Barra: 'VINCERE AUT MORI', which translates as 'To conquer or die'. It was probably a charm for protection in childbirth.

These seed charms have been referred to in Gaelic as 'Airne Moire' or 'Mary's Nut'.