Key in a search term below to search our website.

Key in a search term below to search our website.

This witch's iron collar (or jougs) was owned by the parish of Ladybank in Fife in the 17th century.

Date

17th century

Made from

Iron

Dimensions

90 mm H x 155 mm D

Museum reference

On display

Scotland Galleries (Level 1), Monarchy and Power, National Museum of Scotland

Did you know?

James VI's interest in witchcraft was linked to his belief that he was the Devil's greatest enemy on earth.

“Though shalt not suffer a witch to live.- Exodus 22:18

This iron collar or 'jougs' was once attached to the wall of the Parish Kirk of Ladybank, Fife. Its purpose was to hold offenders by the neck and expose them in a public place for censure and ridicule for a variety of misdemeanours, including witchcraft.

The Scottish witch craze began in earnest in 1590, with the trial of a group of people, mainly women, from East Lothian. They were accused of meeting with the Devil and conjuring up storms to destroy James VI on his return from Denmark with his bride, Anne. The king, who personally examined the accused, composed his own treatise on the subject, Daemonologie.

The trial of the North Berwick 'coven' began a pattern of persecution of suspected witches by torture and capital punishment. Witch hunts often took place at a time of upheaval, warfare, famine or disease. In Scotland, the main phases of the witchcraze were the late 1620s, the late 1640s and 1661-2.

Above: Newes from Scotland, a contemporary pamphlet dealing with the North Berwick witch trials. This woodcut depicts alleged events of 1590-1, including the king's ship passing through stormy waters, the school-master recording the Devil's commandments, and a pedlar lying in a merchant's cellar in France. to which he was spirited on discovering the witches.

In the late 16th-and 17th-century century Scotland, between three and four thousand people were tortured and executed as ‘witches', a group identified as threatening social stability. The methods of torture involved devices such as thumbscrews and branks (an iron muzzle).

Accusations of witchcraft spread rapidly as, under torture, suspects provided the vivid details and names they believed their interrogators wanted to hear. During his trial in 1649, Patrick Watson blamed his own wife for bringing the Devil into their home. Patrick was later strangled and burned after being identified as a witch by John Kincaid, a professional witch pricker who pricked suspects with a needle until he found a spot which did not bleed.

Most of those accused were women – spinsters or widows with no means of support and unable to defend themselves. Often they had local reputation for herbal remedies, folk medicine and healing.

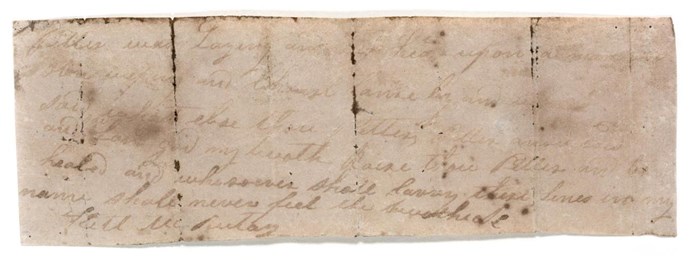

Above: Written charm to cure toothache bought from a professional witch at Kishorn, Lochcarron, and worn round the neck by a shepherd.

The persecution of witches in Scotland was part of the witch craze phenomenon which swept Europe. A tract written by two German monks in 1490, Malleus Maleficarum, linked elements of folk belief with a conspiracy to overthrow the Church of Rome.

Scottish Presbyterians adapted these ideas and accused Roman Catholics of using witchcraft to threaten the Reformed Church. They believed the Church of Scotland had a covenant with God, and that the witches had entered a pact with the Devil. They saw the so-called witches as the enemies of the church, state and people of Scotland.

It's possible that hundreds of those convicted of witchcraft were strangled and burnt at the stake on the execution ground now covered by the Edinburgh Castle Esplanade.

The Witches’ Well, a cast iron drinking fountain, was installed on the Esplanade in 1894 as a modest memorial to those who suffered and died there. The plaque states:

“This fountain, designed by John Duncan, R.S.A, is near the site on which many witches were burned at the stake. The wicked head and serene head signify that some used their exceptional knowledge for evil purposes while others were misunderstood and wished their kind nothing but good. The serpent has the dual significant of evil and of wisdom. The foxglove spray further emphasises the dual purposes of many common objects.

Calls have been made for a large scale public memorial to mark those who were persecuted, as well as a series of plaques across Scotland.