Piecing together the graves of medieval Whithorn

News Story

Medieval Christians were buried in simple shrouds without possessions. Death was seen as a journey of the soul, leaving behind earthly things. That is, except for bishops, who were sometimes buried in their full regalia.

Excavations at Whithorn, Galloway, have brought us face to face with the power of bishops in medieval Scotland.

Content warning: This page contains images and descriptions of archaeological human remains.

Discovering the Whithorn graves

The graves were discovered by accident. While waterproofing the vault of the medieval crypt in 1957, workmen encountered three stone coffins. Careful excavations over the next decade revealed they were part of a series of well-built graves, laid before the high altar. Only a privileged few were allowed to be buried so close to the tomb of St Ninian, the founder of Whithorn. With excavation, we began to piece together who might be buried here.

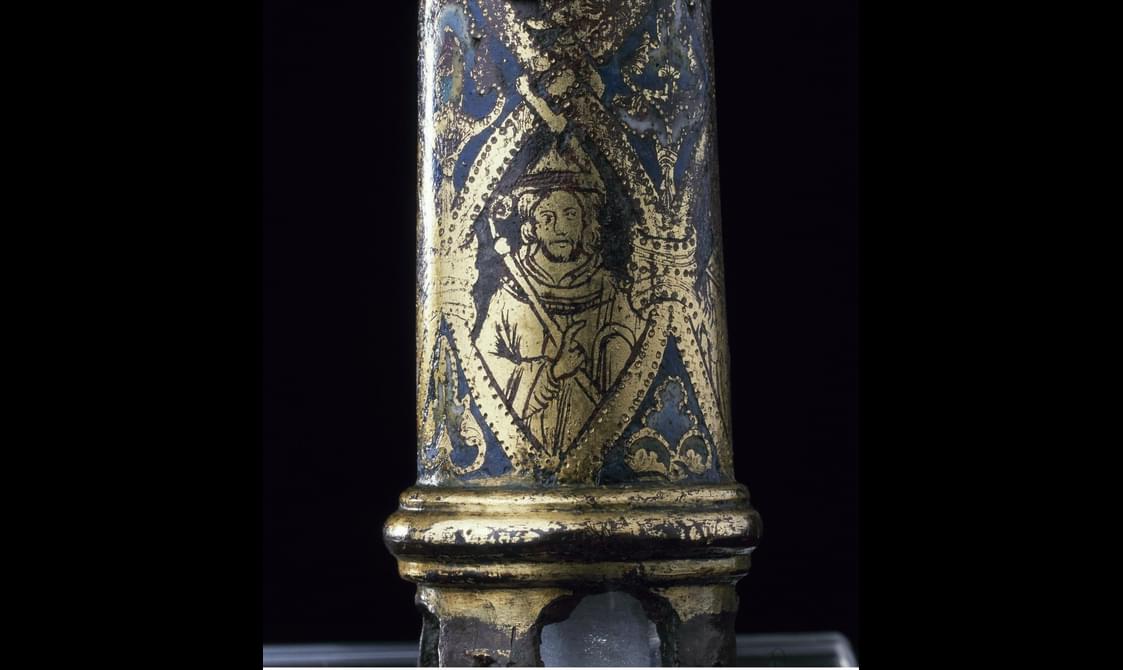

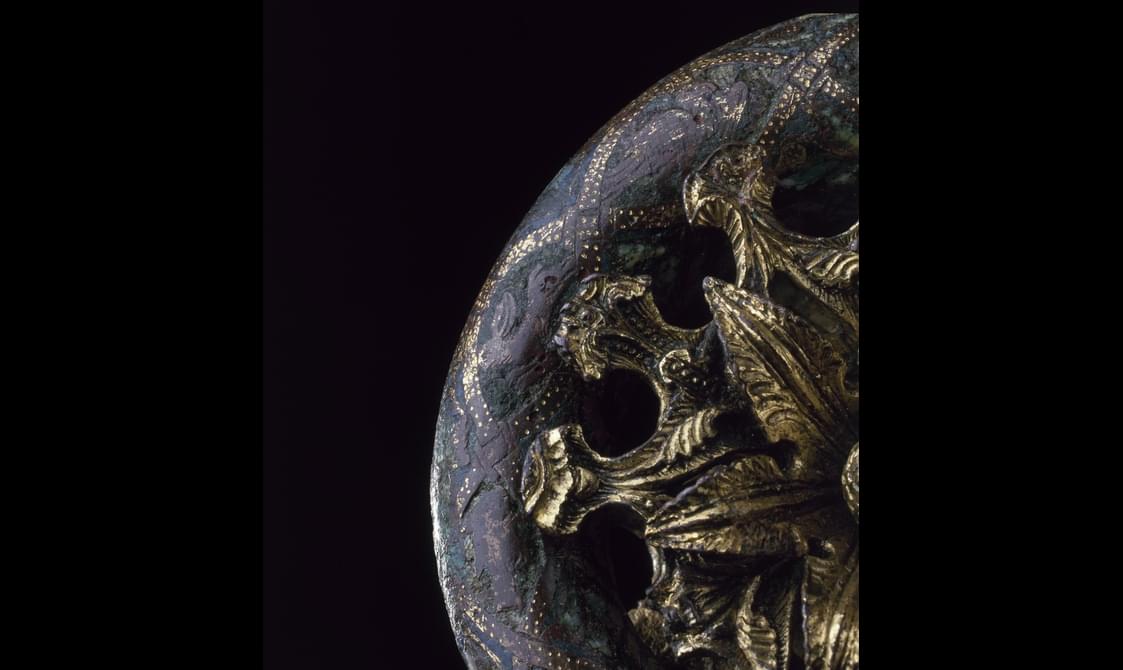

The objects found in the graves ranged from buckles and brooches to rare altar vessels and the insignia of clerical office. The most important finds were the ornate staffs found in three of the graves. Two were carved wooden staffs which survived only in fragments, but one was a late 12th century gilt bronze crozier with enamel inlay.

The bishops' graves under excavation.

What can a crozier tell us?

The crook-headed staff, or crozier, was the symbol of bishops and abbots. They're seen on carved stones and the chess pieces of the Lewis Hoard.

By the 13th century, bishops were buried wearing their vestments with croziers and other altar vessels.

One of the Whithorn burials had a set of 110 small metal spangles around the head. This represented a bishop’s mitre: the ceremonial headdress of the bishop.

The Whithorn graves also included dress accessories, altar gear, and decorated stone coffins. Individuals buried with these may have been priests or wealthy patrons of the Church, buried in their finery next to the bishops.

Image gallery

Whithorn Crozier. Museum reference H.1992.1833.

Whithorn crozier frame with champlevé enamelling. Museum reference H.1992.1833.

Golden saint image on the Whithorn Crozier frame. Museum reference H.1992.1833.

Whithorn Crozier floral cluster head. Museum reference H.1992.1833.

What objects were found in the graves?

Bishops and priests were identified by the liturgical vessels, or objects used in the Christian Mass ritual, buried with them. These include at least five chalices and three patens, but more were likely degraded or lost.

These vessels served the wine and bread transformed into the blood and body of Christ during the ritual of the Mass. However, only some of these were actually used.

The silver vessels were decorated with crosses or the symbol of the Manus Dei, the hand of God. These seem to have been used for some time before being left in the grave.

Others, however, were made of pewter, or lead alloyed with tin. These were copies of real altar vessels, made as stand-ins for clerical burials.

Whithorn Paten. Museum reference H.1992.1837.

Whithorn Chalice. Museum reference H.1992.1838.

Religion in Whithorn

The ruined medieval church where these graves were found was the Premonstratensian priory of Whithorn. It also served as the cathedral for the bishops of Galloway, who were, for a time, buried before the high altar. The cathedral and priory had been re-founded in the 12th century, but Whithorn had been a famous church for much longer.

The first named Christian in Scotland is Latinus of Whithorn. He lived in the 5th century, according to a Latin-inscribed stone commemorating him and his daughter. The site later became known as the shrine of St Ninian, a legendary bishop remembered for his missionary work in southern Scotland. By the 8th century AD, Ninian’s life story was famous, and his shrine continued to receive pilgrims and royal patronage throughout the medieval period.

Carved wooden effigy of a bishop, thought to be St Ninian. Museum reference H.KL 219.

The Whithorn bishops

The earliest graves were radiocarbon dated to the 11th and 12th centuries, but most are from the 13th and 14th centuries.

There were 28 graves in total, including eight with grave goods such as clothing and objects buried with the dead. Some of these would have been wealthy donors and their families.

At least four individuals wore gold or silver rings, set with amethysts, emeralds, and sapphires. Even those without objects in the graves would have been part of an exclusive club, enjoying the benefit of burial near the saint. Among them were at least nine infants and children, and at least four women. This means that not everyone buried here was a member of the clergy.

The finds and human remains were allocated to National Museums Scotland. This has allowed for new scientific analyses to be carried out which reveals more about medieval Whithorn.

Stable isotope analysis studies the chemicals absorbed into bones and teeth, and tells us about diet and mobility. This showed that most of the bishops came from outside of Galloway, and ate a marine-heavy diet.

Clergy and other devout Christians were expected to fast before important festivals, and abstain from eating meat on Fridays and Saturdays. Those with the means to do so could substitute fish on those days.

Image gallery

Whithorn gold finger ring. Museum reference H.1992.1835.

Whithorn gold finger ring inlaid with ruby. Museum reference K.2009.212.

Whithorn silver finger ring. Museum reference H.1992.1836.

The facial reconstruction of Bishop Walter

It may be possible to identify some of these individuals using the historical sources. The evidence from radiocarbon dating, grave objects and stable isotope analysis potentially identifies one of the graves as that of Bishop Walter (1209-1235). His was one of the most prominent burials for location and furnishings.

Bishop Walter was known to have worked in the diocese of York, becoming bishop of Whithorn in 1209. The individual in the grave was a mature adult male, with possible signs of obesity, and a diet high in fish. His teeth reveal he was raised in Galloway.

He was buried dressed in a clay-bonded stone coffin with wood lining, along with a wooden crozier, a gold ring set with rubies and emeralds, and a copper-alloy buckle with fragments of textile.

A team from the University of Bradford has been able to reconstruct the facial features of some of the remains found during excavation. Facial reconstruction is the process of estimating facial appearance from a skull with forensic accuracy. It produces a picture of how an individual may have looked.

Another individual was a priest with a cleft palate. New genetic sequencing is being carried out on the remains of this individual in partnership with the Crick Institute, London. This will help determine eye and hair colour.

Facial reconstruction of Bishop Walter.

The facial reconstruction of Bishop Walter prior to adding skin layers, colour, and texturing.

A significant discovery

Discoveries like these are rare opportunities to ask new questions about medieval life. This excavation showed us how a narrow elite were laid to rest.

However, it also contributes to ongoing debates and anxieties about the afterlife and the fate of the soul, even for those who spent their lives cultivating an understanding of the spiritual world.