Architecture trail

The National Museum of Scotland is housed in magnificent buildings. Find out about its striking architectural details below, and explore them further on your next visit to our Museum.

This trail explores the architectire and building history of the National Museum of Scotland. The building's design incorporates many references to Scotland's history and landscapes.

Flick through the stops below to guide you around the Museum. Be sure to check the museum map as you go along.

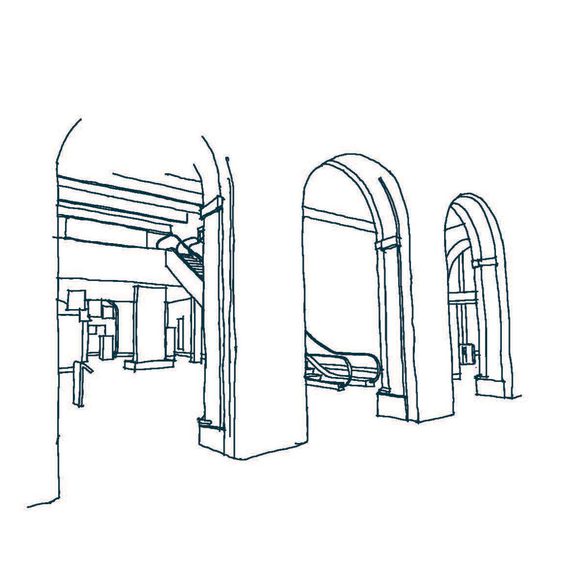

1- Entrance Hall

Location: Entrance Hall, Level 0

The vaulted Entrance Hall was originally a basement storage area. It was converted to a new street-level entrance as part of a major redevelopment of the Museum led by Hoskins Architects. Completed in July 2011, the project improved access to the Victorian building, provided new visitor facilities and restored the exhibition galleries.

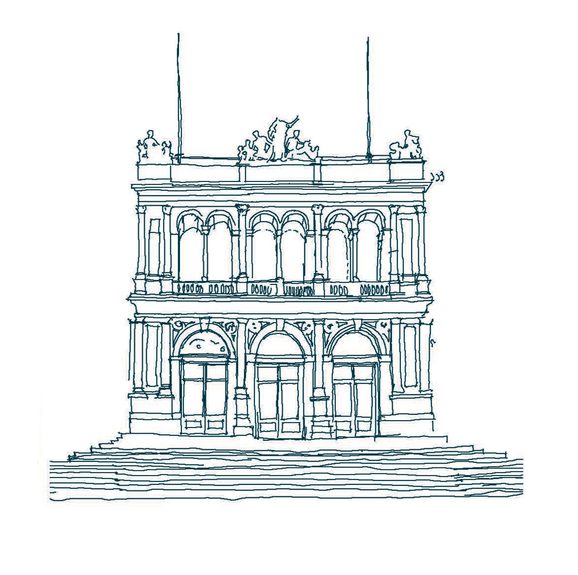

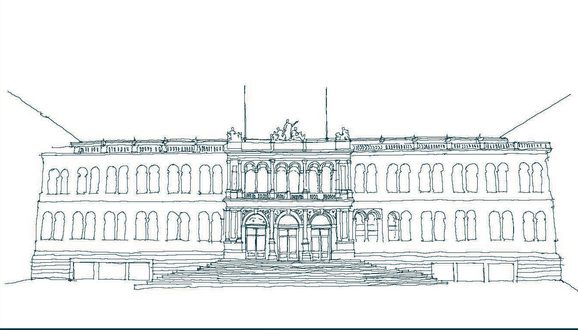

2- Front facade

Location: Chambers Street

The sculptures on the front façade of the Museum are by Edinburgh sculptor John Rhind. The central figure represents Science, and the two groups on either side depict Natural History (east) and Applied Art (west). The six heads above the doorways are of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, James Watt, Charles Darwin, Michelangelo and Sir Isaac Newton.

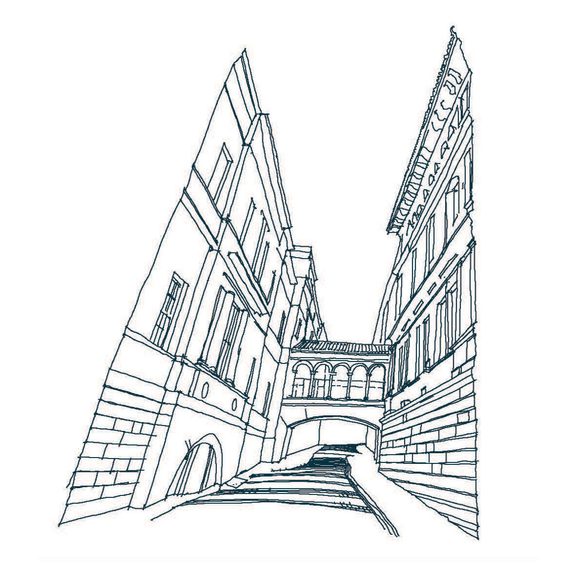

3- Behind closed doors

Location: West College Street

There are doors that lead to a bridge which links the Museum to the University of Edinburgh across West College Street. Built in the 1860s, the design echoes the 17th-century Bridge of Sighs in Venice. A student ‘raid’ on the food and drink at a museum reception led to the closure of the bridge in 1871. It was opened temporarily in the 1920s and ‘30s so that students could attend lectures but has been closed since then.

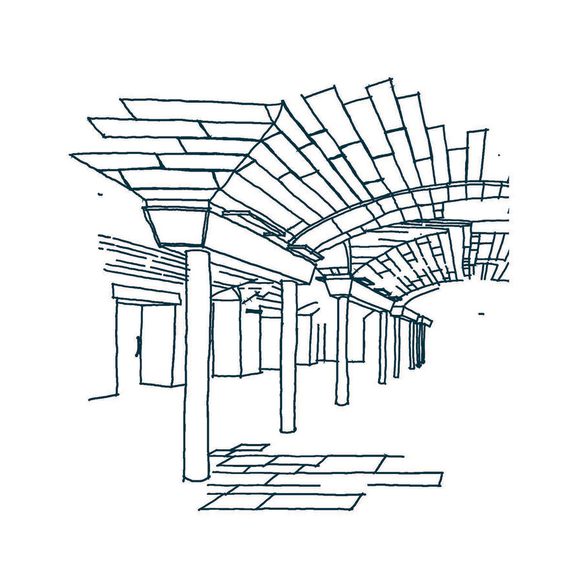

4- Inspired by the Crystal Palace

Location: Grand Gallery, Level 1

The Crystal Palace, built for the Great Exhibition London in 1851, was the inspiration for the design of this Museum, by Captain Francis Fowke. The success of the Exhibition led to the founding of museums such as the Science, Natural History and Victoria and Albert museums in London, as well as the National Museum of Scotland.

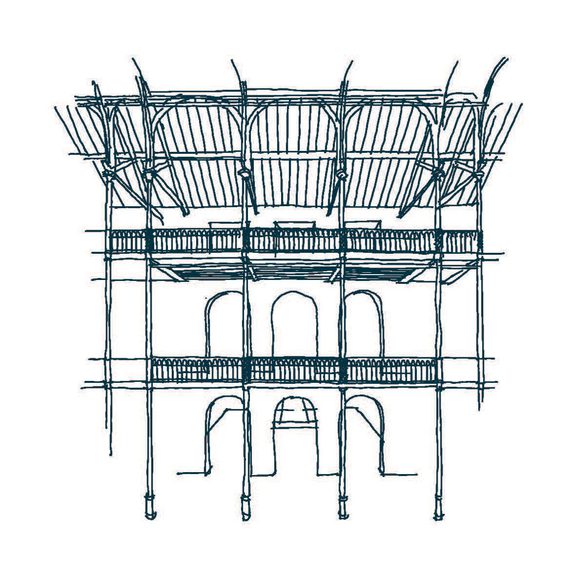

5- An engineering achievement

Location: Grand Gallery, Level 1

With a glass roof over 80 metres long and 24 metres high, soaring columns and sweeping balustrades, the Museum was at the forefront of engineering and design when it opened in 1866. The slender cast iron pillars were the narrowest possible that could support the structure. An innovative ventilation system in the roof incorporated gas lighting, which meant the Museum could open to the public after dark.

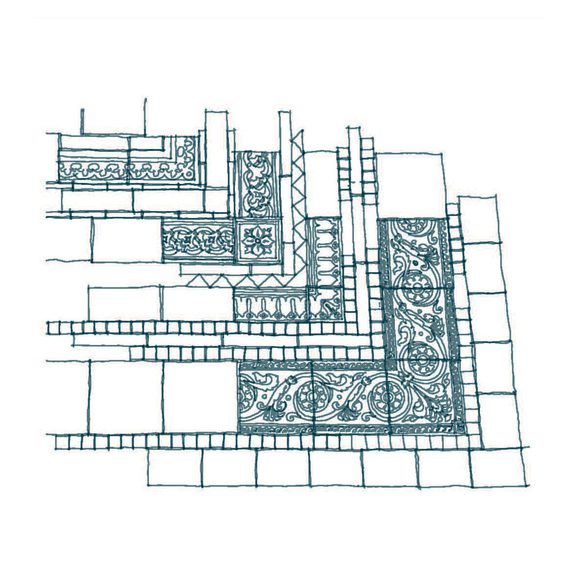

6- Original floor tiles

Location: Grand Gallery, Level 1

The decorative floor tiles are from the original tiled floor of the Grand Gallery. They were produced by the famous ceramic manufacturer Minton & Co, in Stoke-on-Trent. When some of the tiles needed replacing in the 1990s, the company manufactured replacements employing the same method that was used to make the originals.

7- The piazza

Location: Chambers Street

In July 2016, a pedestrian piazza was opened in Chambers Street to mark the 150th anniversary of the founding of the Museum. A statue of the Scottish neoclassical architect William Henry Playfair was commissioned from sculptor Alexander Stoddart and installed opposite the restored statue of William Chambers, the publisher and former Lord Provost of Edinburgh.

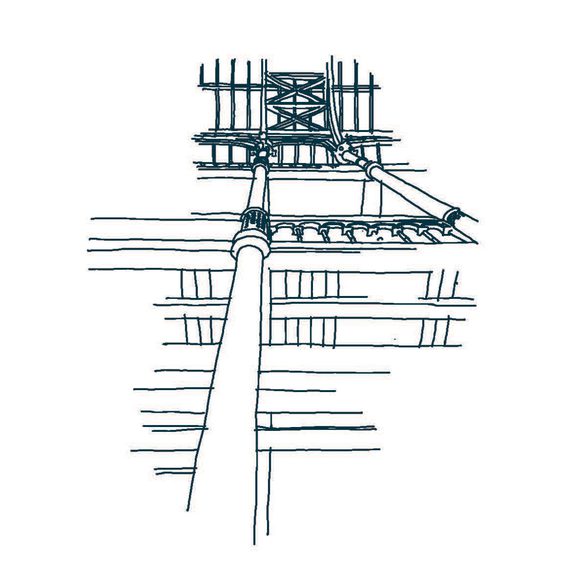

8- Decorative radiators

Location: Around the Museum

Designed to fit around the slender iron pillars, there are more than 50 of the original radiators still operating in the Museum. The radiators and the ventilation system were designed by Wilson Weatherley Phipson, a Birmingham-based engineer who worked on many prestigious building projects, and with such distinguished architects as Gilbert Scott and William Burges.

9- The Edinburgh Museum of Science and Art

Location: Chambers Street

The Edinburgh Museum of Science and Art – as it was originally called – was designed by Royal Engineer Captain Francis Fowke, who was also responsible for the great architectural designs of the Royal Albert Hall and the Victoria and Albert Museum. The foundation stone of the Museum was laid in 1861 by Prince Albert, his last public duty before his death. The building was opened on 19th May 1866.

10- Transforming the Museum

Location: Collecting Stories, Level 1

In July 2011, the Museum marked the completion of a major redevelopment by Hoskins Architects, founded by the late Gareth Hoskins. This project transformed the Victorian building, opening it up to all visitors, improving facilities and reinstating galleries. As a result, the Museum received the RIAS Andrew Doolan Best Building in Scotland Award, 2011.

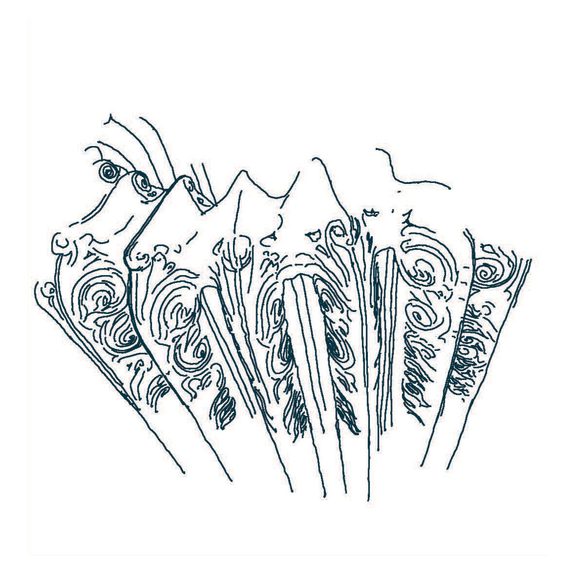

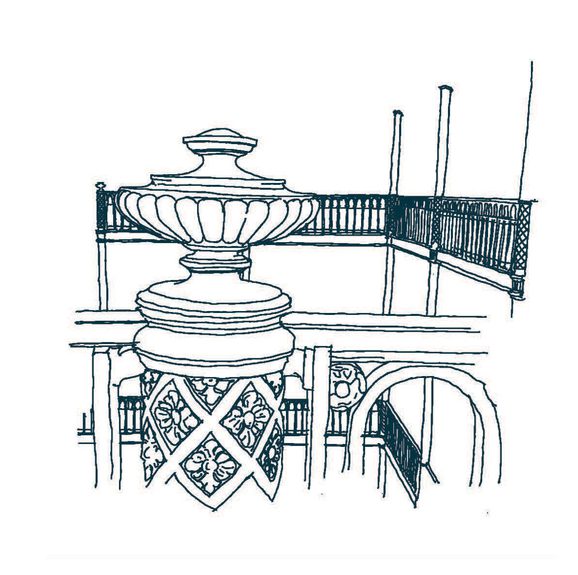

11- Neoclassical designs

Location: Around the Museum

These finial decorations are designed in the shape of neoclassical vases. The restrained use of this motif, together with other floral and foliage motifs, slender iron pillars, decorated capitals, rounded arches and curving staircases are part of the simple pared-back design of the Victorian building.

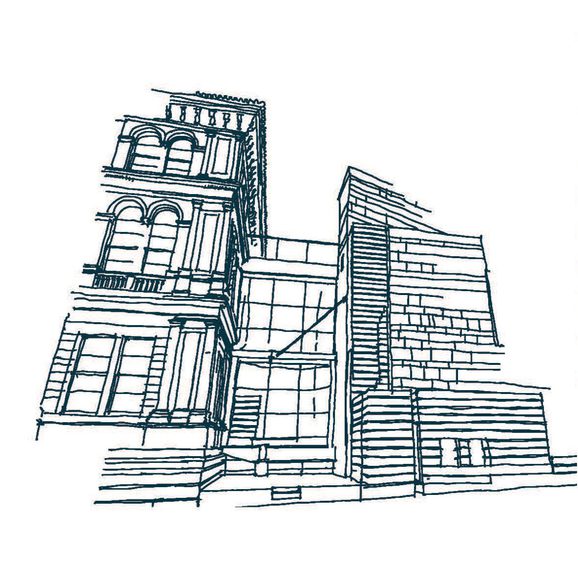

12- The 'gap'

Location: Chambers Street

The design for the Museum of Scotland by architects Benson & Forsyth acknowledged the gap between the old and new buildings with a glass curtain wall. The stone wall of the new building begins beyond this with a rusticated stone pilaster that pays homage to the original Victorian building.

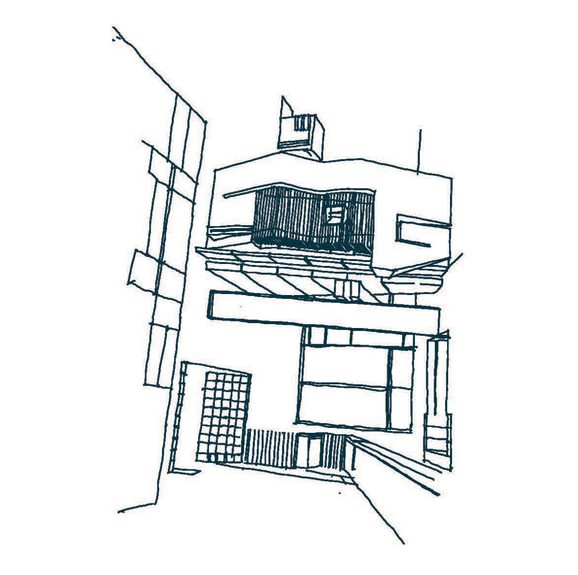

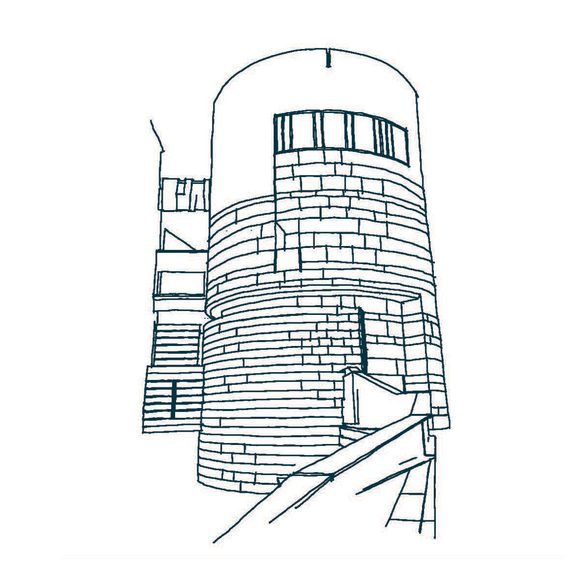

13- Museum of Scotland building

Location: Tower Entrance, Chambers Street

Opened in 1998, the Museum of Scotland building was designed by architects Benson & Forsyth. Their design drew on the work of the modernist architect Le Corbusier and was also influenced by Scottish vernacular architecture, in particular medieval castles with spiral staircases, towers and narrow ‘arrow loop’ windows.

14- Reflecting Scotland

Location: Hawthornden Court, Level 1

The design of the Museum of Scotland incorporates many references to Scotland’s history and landscapes. The vertical lines of the walkways over Hawthornden Court are inspired by the strings of a Scottish Clàrsach and narrow arrow loop windows recall medieval fortifications. The exterior of the building is clad in Morayshire sandstone, described by architect Gordon Benson as ‘the oldest exhibit in the building.’