Key in a search term below to search our website.

Key in a search term below to search our website.

In 1966 China entered a ten-year period of immense social change. Inspired by Mao Zedong, the Cultural Revolution was a time of mass destruction and suffering, but also Cold War diplomacy with the United States that ended the country’s isolation.

On 1 June 1966 an editorial in the Communist Party’s newspaper The People’s Daily called for the destruction of the “Four Olds”: pre-revolutionary ideology, culture, customs and habits. In August, the Party leadership declared the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution to smash remnants of the old China. A radical faction, later dubbed the “Gang of Four”, emerged to direct the campaign through the Central Cultural Revolution Group.

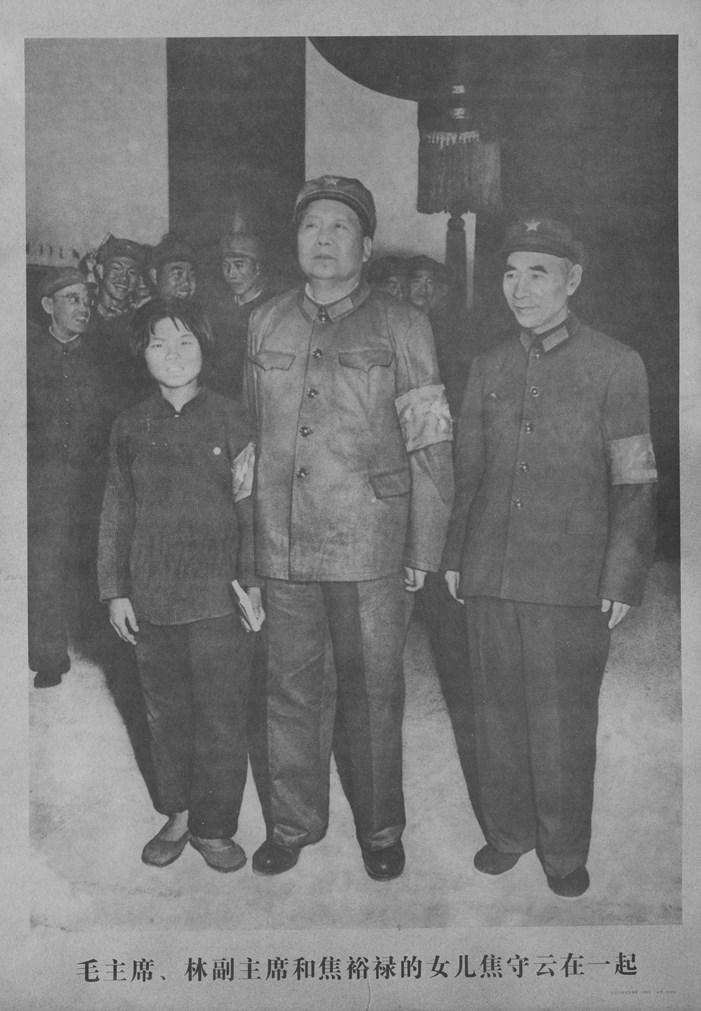

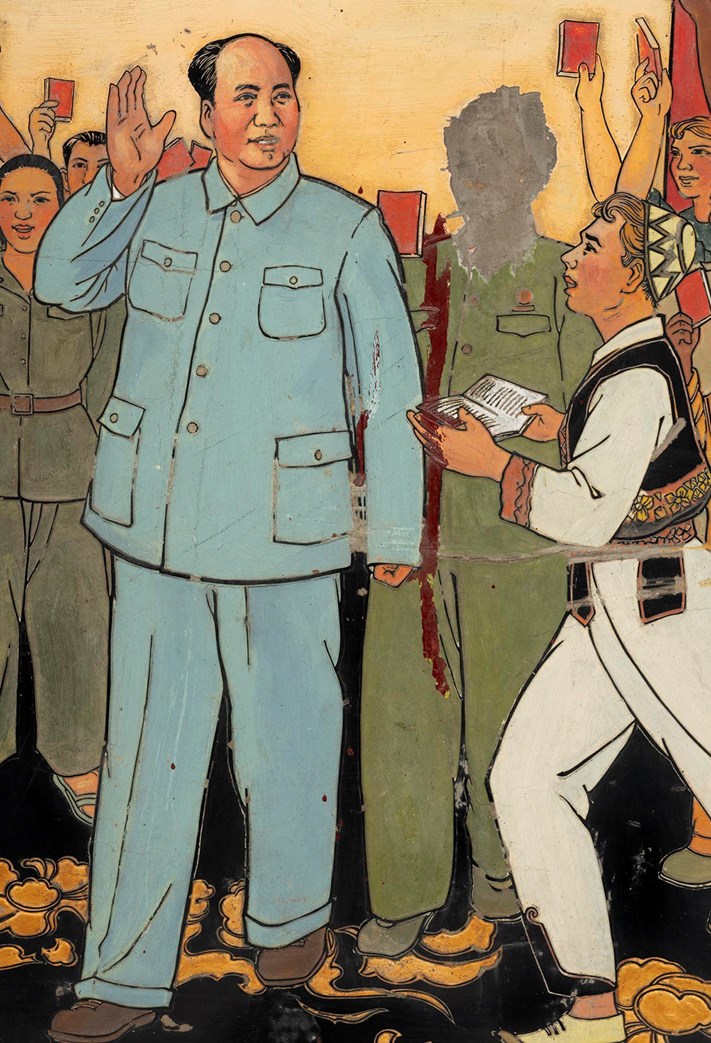

At the forefront of the Cultural Revolution were the Red Guards, a movement that began among the young in schools and universities. Red Guards held “struggle sessions” where Party officials and wealthier citizens were denounced as “class enemies” before huge crowds. Victims were typically forced to wear dunce caps in public squares or paraded through the streets in ritual humiliation. They were frequently subjected to physical violence, and many were killed, or committed suicide. Even Party leaders were not immune from the Red Guards’ fury: China’s head of state Liu Shaoqi was purged in 1968. Above all criticism, Mao Zedong appeared at vast rallies of adoring Red Guards in Beijing, along with Minister of Defence Lin Biao.

Mao Zedong and Lin Biao at the Gate of Heavenly Peace during a mass rally of Red Guards in Tiananmen Square, 1966 (V.2013.32.538).

Tasked with rooting out political incorrectness, armed Red Guards set about destroying the physical features of the old society. Street and shop names were changed, libraries ransacked, and religious places of worship desecrated. Historic sites were also targeted, such as the ancient philosopher Confucius’s birthplace at Qufu and the former Imperial Palace in Beijing’s Forbidden City.

Fearing the complete destruction of the country’s heritage, the Chinese premier Zhou Enlai mobilised the People’s Liberation Army to protect the Forbidden City and ordered cultural artefacts exempt from attacks on the “Four Olds”. To regain control of the situation, the Central Cultural Revolution Group was disbanded in 1969, and student Red Guards were sent to the countryside, along with urban intellectuals, to study the peasantry. Army units were deployed in the major cities to restore order.

The leaders of the Cultural Revolution aimed to create a modern mass culture to reflect the new China. The visual arts were mobilised for propaganda to inspire strong emotions in the masses. Mao’s wife Jiang Qing, a member of the Gang of Four, was one of the principal architects of the new culture. She became closely associated with the major popular entertainment of the Cultural Revolution: the eight ‘model performances’ consisting of five operas, two ballets and a symphony.

The model opera Shajiabang is set in rural Jiangsu during the Japanese occupation and portrays the heroism of the communist New Fourth Army and its peasant supporters. Shajiabang was promoted by Jiang, and after official recognition in 1967, performed by travelling theatre troupes across China. Jiang described the opera’s adaptation by the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra as “worker-peasant-soldier symphonic music”. To reach an even bigger audience the opera was made into a film by the Changchun Studio in 1971.

We will not surrender one inch of our motherland's mountains and rivers from Shajiabangposter, Hebei People's Publishing House, 1973 (V.2013.32.196).

Despite the Cultural Revolution’s mission of eradicating the old ways and rejecting foreign capitalist decadence, the model performances contain both traditional Chinese artforms and Western influences. Chinese folk dance and martial arts are combined with ballet and modern dance steps from the West.

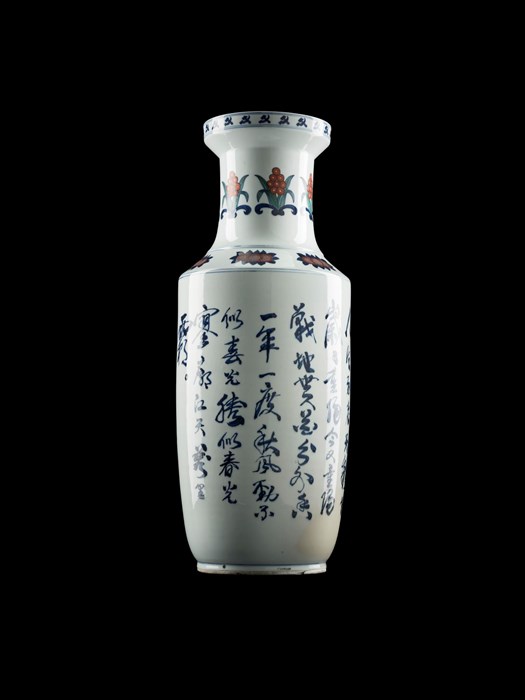

Scenes from the performances were also reproduced in porcelain form, along with other ensembles celebrating revolutionary achievements. Following the Maoist line, factories in Jingdezhen, the historic centre of the ceramics industry, produced vases and figurines illustrating revolutionary themes.

Celebrating the Harvest porcelain figurine, Jingdezhen, c. 1970 (V.2009.232).

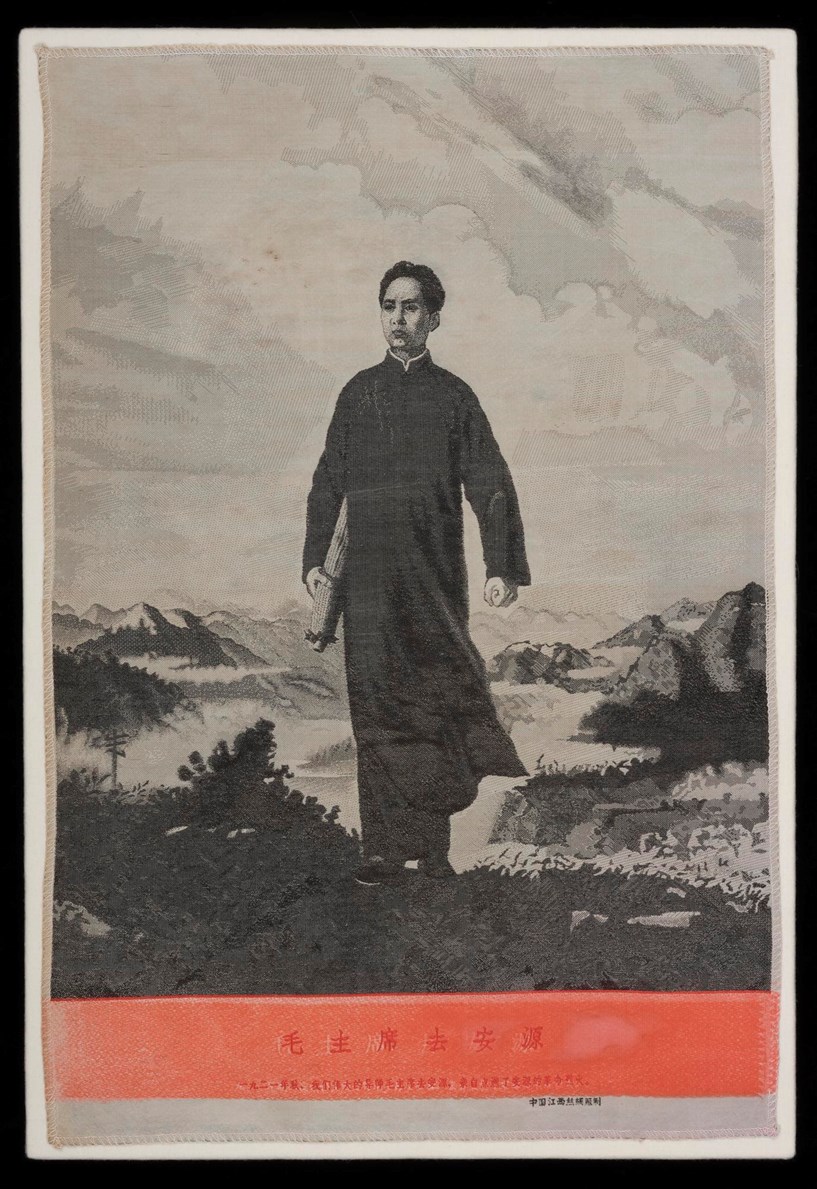

Mao was the icon of the Cultural Revolution. His image appeared everywhere on posters, ceramics, badges and banners. One of the most commonly reproduced portraits was the romantic Chairman Mao Goes to Anyuan painted by Liu Chunhua in 1967. In this ‘model image’ Mao is seen travelling to the mining town in eastern Hunan province to organise a strike in 1921. The original painting was inspired by a Red Guard exhibition praising Mao, but obscuring Liu Shaoqi’s decisive role in the actual events in Anyuan.

Chairman Mao Goes to Anyuan, Jiangxi Silk Factory, c. 1968 (V.2007.17).

In another model image Mao is depicted as the sun with beaming rays, often giant-sized and raised high in the sky like a god. Chinese citizens were expected to learn and quote the basics of ‘Mao Zedong Thought’ from his writings compiled in The Little Red Book. Songs and dances were devised for people to display their loyalty and devotion to the Chairman.

Long Live Chairman Mao porcelain vase with his poem The Double Ninth on reverse, Jingdezhen, 1968 (V.2009.230).

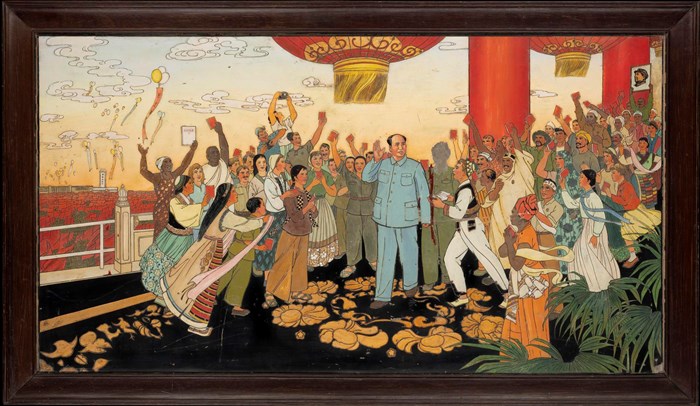

Although Mao’s cult status peaked in the period 1966 to 1968, he was in an insecure position at the start of the Cultural Revolution. He was reputed to be in ill health and losing his grip on power. Mao’s flagship modernisation project the Great Leap Forward had been a catastrophic failure. His break with the Soviet Union in the early 1960s had left China without access to vital trade and new technology, hindering the country’s progress. A major theme of Maoism in the late 1960s became the Chinese nation’s need for self-reliance. China sought to replace the Soviet Union as the main sponsor of anti-colonial revolution in the Third World, offering an alternative path to modernity from the superpowers.

The Socialist Peoples of Asia, Africa and Latin America love Chairman Mao lacquer plaque, Yangzhou, 1968.

The period of the Cultural Revolution coincided with the end of Mao’s life. Among the factions in the Communist Party leadership, the question of Mao’s successor was bitterly contested. After encouraging the Red Guard movement, Lin Biao was personally anointed by Mao in 1969. When Lin clashed with Jiang Qing the following year, Mao turned against him, and he began to fear for his safety.

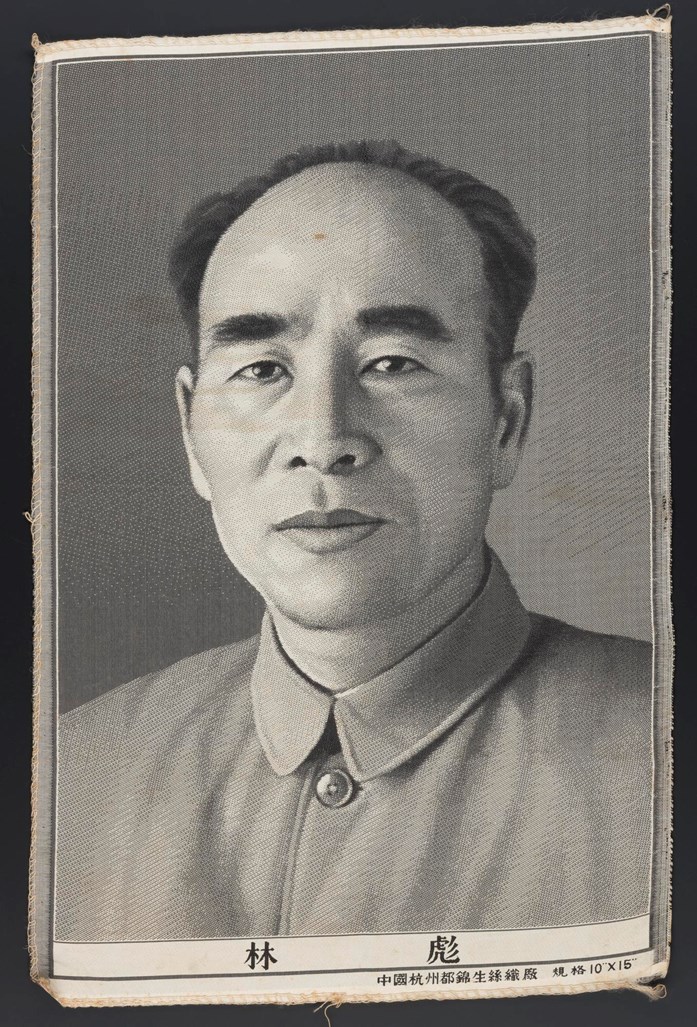

Embroidered silk portrait of Lin Biao, c. 1966 (V.2013.32.360).

Lin mysteriously perished in a plane crash over Mongolia on 13 September 1971. The reasons for Lin’s flight to the Soviet Union are unknown and historians differ over his motives. After his death, Lin was accused by the Party leadership of plotting a coup against Mao and planning his assassination. Lin was retrospectively excised from revolutionary artworks and monuments.

Detail of The Socialist Peoples of Asia, Africa and Latin America love Chairman Mao, with Lin Biao’s face erased.

Intact depictions of Lin are therefore rare. Surviving artefacts are often those placed in storage in the early 1970s. After the Nanjing Yangzi River Bridge opened in 1968, General Xu Shiyou commissioned a commemorative plaque as a gift for his superior Lin. In the wake of Lin’s disgrace, the expensive lacquer plaque, inlaid with mother of pearl, was mothballed by the factory.

Detail of the plaque celebrating the opening of the Nanjing Yangzi River Bridge made by the No. 1 State Lacquer Factory, Yangzhou, c. 1970 (K.2000.196).

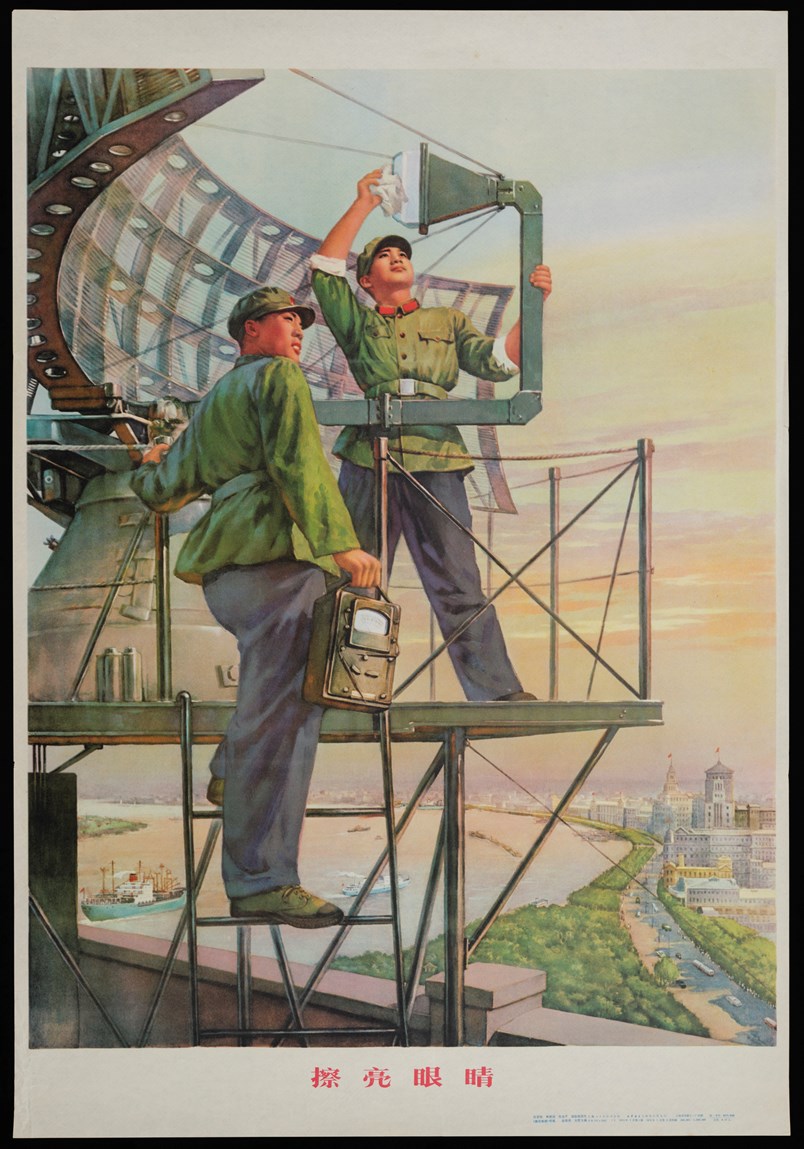

The Cultural Revolution exposed a long-term conflict among China’s revolutionaries between radical Maoists and moderates who favoured development and international trade. Mao’s death in September 1976 triggered the arrest of the Gang of Four the following month, including Mao’s new heir apparent Wang Hongwen. The Gang of Four’s downfall signalled the rise of a new more pragmatic Chinese leadership. Rehabilitated by Mao near the end of the Cultural Revolution, Deng Xiaoping came to power in 1978. The new leader announced a far-reaching reform programme based on increasing Chinese scientific and technological knowledge. China would enter a new era of economic growth, following the example of Japan’s modernisation in the late nineteenth century.

Sharpen One's Vigilance poster, Shanghai People's Publishing House, 1975 (V.2013.32.327).

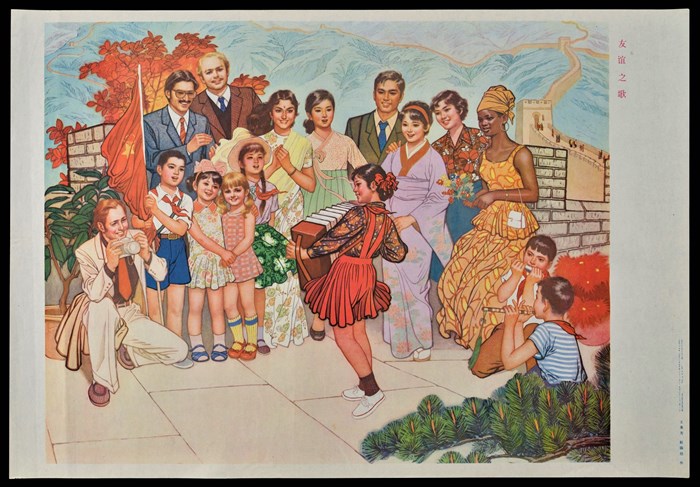

During the Cultural Revolution the political landscape of the Cold War changed dramatically. China realigned her foreign policy, abandoning previous relations with many fellow communist states. In the chaos following Lin’s death, China reached détente with the United States when Mao met President Richard Nixon in 1972. At this time, Chinese hostility to her northern neighbour increased with Mao preparing for war with the Soviets. China reorientated toward new regional allies like Pakistan and Iran who were anti-Soviet. By the close of the 1970s, memories of the Cultural Revolution were fading to be replaced with a new ethos of opening up to global markets.

The Song of Friendship poster, Tianjin Art Publishing House, 1979 (V.2013.32.320).