Key in a search term below to search our website.

Key in a search term below to search our website.

Discover the history of a 17th-century stone carving which reflects changing tastes in interior design through the years.

Date

Early 1600s

Made by

An unknown English sculptor, based on an engraving by Crispyn de Passe

Made from

Limestone

Dimensions

135cm high x 171cm wide x 15cm deep

Weight

300kg

Acquired

1976, from the sale of artefacts from the hunting lodge of Reginald Brett, 2nd Viscount Esher

Museum reference

On display

Traditions in Sculpture, Level 5, National Museum of Scotland

Did you know?

It is thought that the elaborately decorated frieze at the bottom of the sculpture was not originally intended to sit directly beneath the narrative but was probably designed as part of a much larger fire surround.

Fleet of foot princess Atalanta declared she would only marry a man who could outrun her. Cunning Hippomenes challenged her to a race. As they ran, he distracted Atalanta with three golden apples from the goddess of Love, Aphrodite, thus winning the race and her hand. In the top left-hand corner of the overmantel, we see Aphrodite giving Hippomenes the apples, while the central scene shows the race itself, with spectators watching.

However, this is not the only tale the overmantel has to tell. Research and analysis carried out by the Conservation department at National Museums Scotland has revealed that the carving also demonstrates changing tastes in interior décor.

Above: Atalanta and Hippomenes overmantel.

The sculptor of the overmantel is unknown, although he is thought to be English. The race scene is based on an engraving by the Flemish artist Crispyn de Passe (1564-1637) and dates from the early 1600s.

The overmantel was acquired by National Museums Scotland in 1976, from the sale of artefacts from the hunting lodge of Reginald Brett, 2nd Viscount Esher. The lodge, in Callander, near Stirling, is now the Roman Camp Hotel.

However, the overmantel did not originate there. An art history student doing a placement at the Museum managed to trace it back to East Acton Manor House, a grand home in London which was demolished in 1911. The building of the house predates the likely date of the overmantel, so its early history is still unknown. However, the richness of the original decoration discovered by the Conservation team suggests it was a highly valued piece from a wealthy home.

Above: The Race of Atalanta and Hippomenes by Crispyn de Passe. (Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam) / Public Domain Mark 1.0

Today, the overmantel is a stony brown. However, using a range of techniques, our Conservation department have discovered that originally it was richly painted with a wealth of colours. This blog post by Artefact Conservator Diana de Bellaigue explains how these colours were revealed, and how, working with Historic Scotland and Napier University, our team have used new technologies to recreate the original design digitally.

The 17th-century palette was similar to that used in paintings and wall paintings of the period, though there are very few English polychrome sculptures with which to compare it. The plaster frieze in the Great Hall at Hardwick Hall in Derbyshire is the closest our conservators have found.

Above: Digital image of the overmantel recreating the Conservation team’s ‘best guess’ at the original colour palette. The team are now working on giving the image a more painterly finish, with gradations of colour, light and shade (see below).

Above: Detail of plaster frieze from the Great Hall of Hardwick Hall. Photo courtesy of The National Trust: Perry Lithgow Partnership.

When did the overmantel lose its bright hues? We can’t be sure. However, images found by our placement student of the overmantel in East Acton House in the late 19th century and two further images uncovered by Colin Muir of Historic Scotland in the house in Callander show that during the late 19th and 20th centuries it was altered dramatically three times to suit its surroundings.

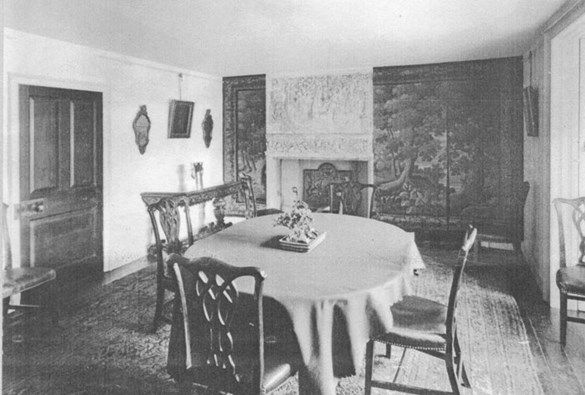

Above: On display at East Acton Manor House in the late 19th century, the overmantel has been grained to imitate wood.

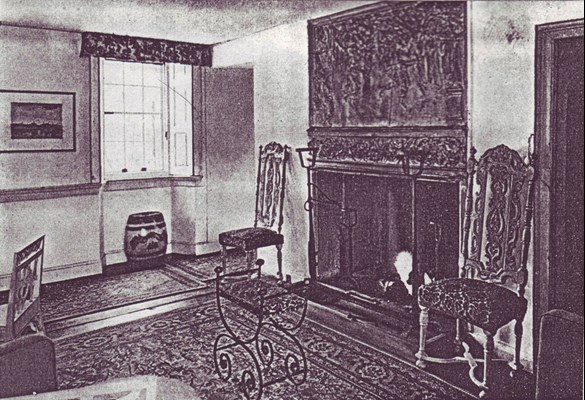

Above: Now installed in Callander in the early 1900s, the overmantel is completely white, imitating plaster or stone.

Above: By 1976 the overmantel is brown again, to imitate wood but possibly also to disguise fire damage.

We’ll never see the overmantel restored to its former colourful 17th-century glory. But through the detailed work of our Conservation department, we can imagine what it would have looked like and follow its story from brightly painted sculpture, a lavish reflection of the tastes of the time, to a more subdued decoration in the late 19th century.

Above: The final digital recreation of the overmantel in all its colourful glory. Working with Diana de Bellaigue, students and tutors from the School of Computing at Edinburgh Napier University have refined the image to produce a more sophisticated and accurate representation of the original effect of the sculpture.