Key in a search term below to search our website.

Key in a search term below to search our website.

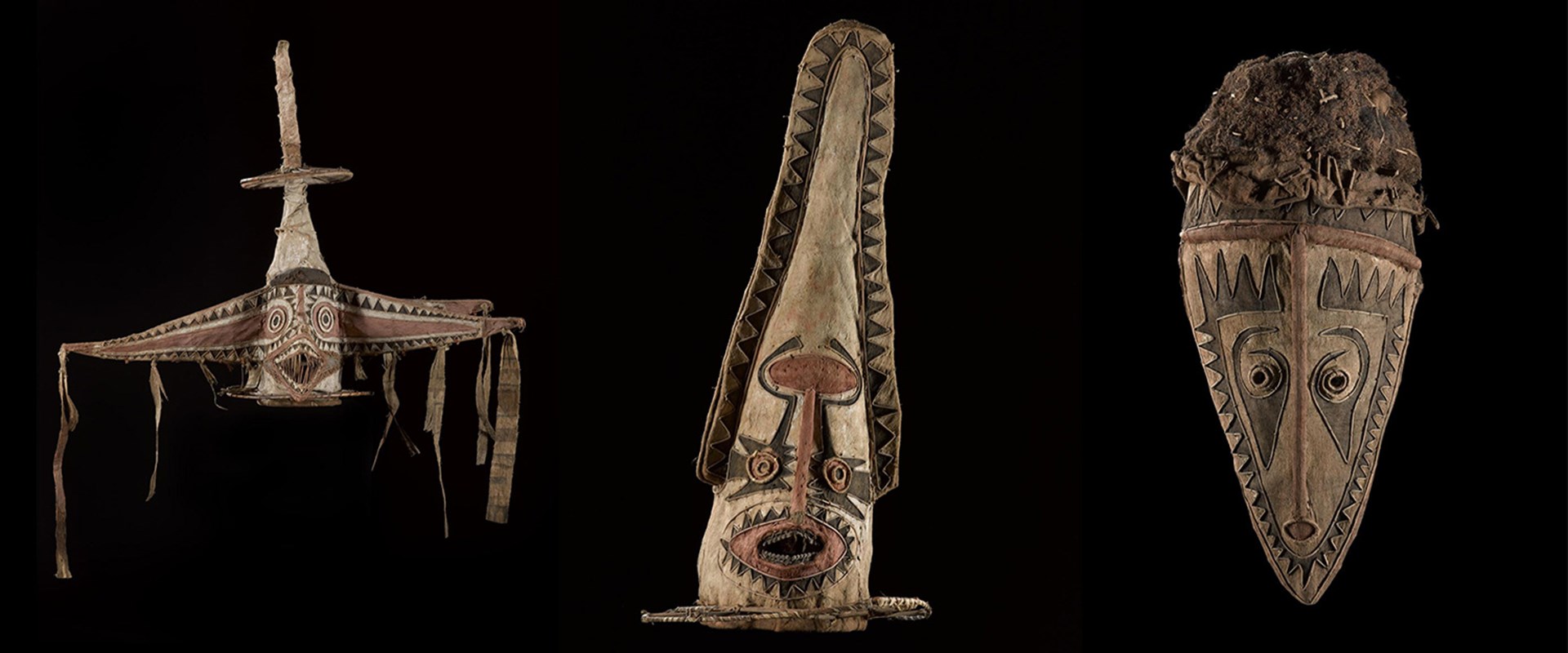

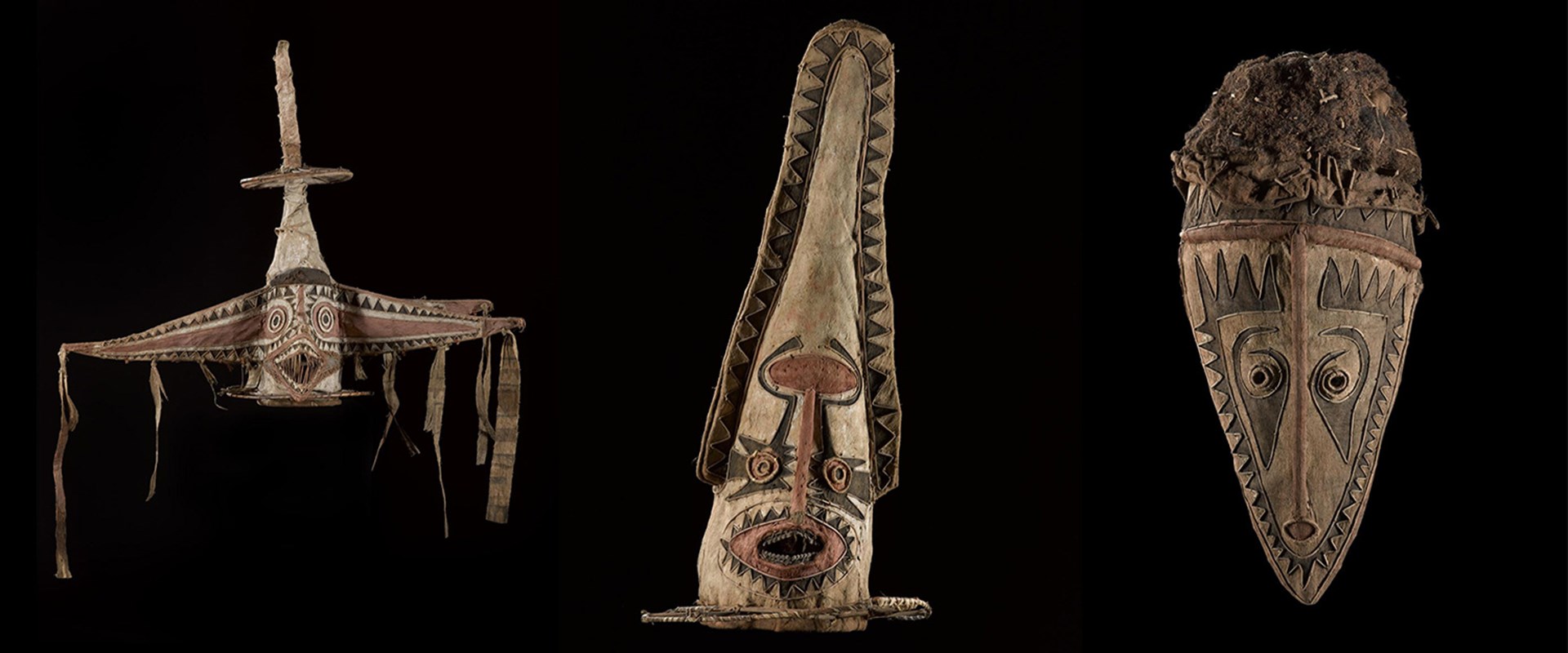

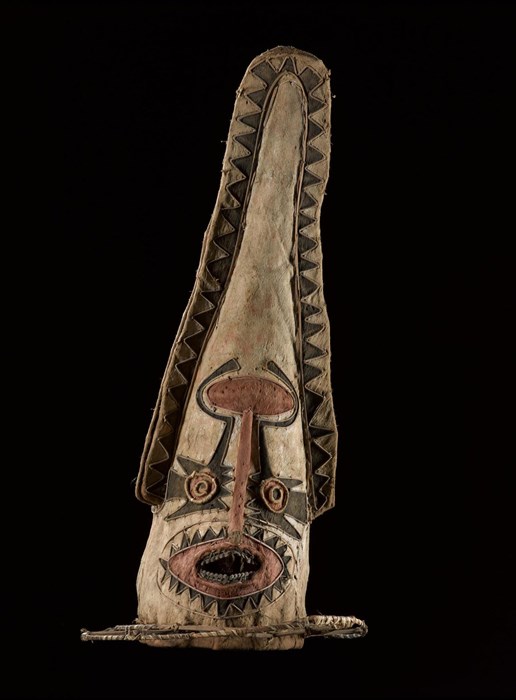

Three dramatic barkcloth masks offer an insight into the traditional beliefs and celebrations of the Elema people from the Gulf of Papua, Papua New Guinea, at the turn of the 20th century.

Date

Late 19th – Early 20th century

Made in

Gulf of Papua, Papua New Guinea, Melanesia, Oceania

Made from

Cane, plant fibre, barkcloth, pigments, human hair

Acquired

Gift of Wellcome Historical Medical Museum

Museum references

Dimensions

A.1951.371 – height 855mm, height including hanging streamers 1235mm, width 110mm, depth 450 mm.

A.1951.372 – height 840mm, max. diameter 400mm.

A.1951.373 – height 745mm, width 385mm, depth 337mm.

New Guinea is the second largest island in the world after Greenland. It lies just below the equator, its closest point only 150km north of the Cape of York Peninsula of Queensland, Australia, with the Torres Strait between. Papua New Guinea is the eastern half of the island, with the Indonesian territories of West Papua to the west. Papua New Guinea also includes the off-shore islands of New Britain, New Ireland, the Admiralty Islands, and others.

Papua New Guinea is the most linguistically diverse country in the world, with 852 recorded languages. That is about 12% of all global languages, spoken by about 0.1% of the world’s population, in a country almost six times as big as Scotland. The island’s rugged landscape is covered in thick rainforest, wide rivers and tropical swamps.

The predominantly accepted theory is that the inhabitants were geographically isolated from each other, so hundreds of distinct indigenous languages developed over thousands of years. However, more recent research into trade and cultural exchange has disproved this theory.

With so many distinct communities, Papua New Guinea developed a great variety of social, cultural and artistic forms of expression, including dramatic masked performances.

The Elema people inhabit the eastern side of the Papuan Gulf, a 300 mile-long bay which curves around from the Torres Straits, above Australia and the Great Barrier Reef, to the modern capital of Papua New Guinea, Port Moresby.

As the three masks discussed here date from before 1924, the rest of this article refers to the traditional society of the time during which they were made, rather than to contemporary Papua, which has changed drastically.

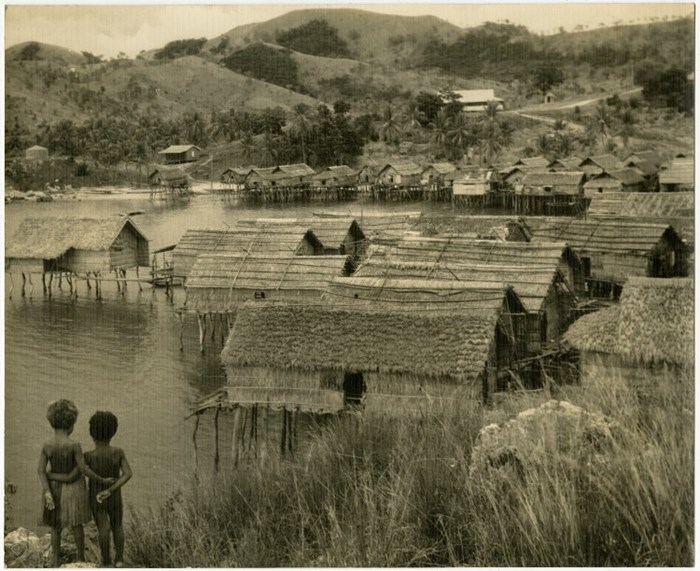

In the late-19th and early-20th century, there were few roads in Papua New Guinea, and transport along the coast and rivers was normally provided by dugout canoe. Society was traditionally divided by gender, with the men living in longhouses called an elavo or eravo, while the women and children lived separately. The longhouses were massive, up to 10 metres wide, 10-12 metres high, and up to 100 metres long.

Above: Photograph of a group of thatch-roofed houses on stilts in an expanse of water; Elevala, Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea, 1900-1930. © The Trustees of the British Museum (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

As well as physically living separately, men and women preserved their own distinct traditional knowledge. Women knew the secrets of fertility, reproduction and childbirth, while the men kept a great many rituals to mediate between the human and spirit worlds. People believed that this knowledge must be guarded and kept secure, as inappropriate knowledge or exposure to rituals by the unprepared or uninitiated could be dangerous and harmful.

While men lived in longhouses, they also created other special buildings used to store masks, ancestor boards and fish-tail drums, which were used for dances and performances. The ancestor boards depict clan emblems and spirits, who watched over the living clan members.

Above: Drum carved from a tree trunk with lizard skin membrane: Melanesia, Papua New Guinea, Gulf Province, Vailala, Elema 19th century.

Three eharo masks from the collection at National Museums Scotland.

The Elema people had an elaborate mask tradition, with masks made of various natural materials including palm leaf, cane and barkcloth. Masked rituals allowed communication with, and attempts to control, the spirits. Spirits represented by masks were generally associated with places or features in the forest, river or sea, rather than deceased ancestors or enemies.

Three different types of masks were made by the Elema:

Masked rituals often involved repetitive singing and drumming, which created a mesmerising atmosphere that left participants in a trance-like state. A sacred instrument often called a ‘bullroarer’ was also used. When swung around in the air, it produces an unearthly sound that is believed to be the voices of the spirits. The sound of the bullroarer was sometimes used as a warning to the uninitiated, particularly women, to hide out of the way so as not to see the procession of sacred objects which could harm them.

Above: Bullroarer made of wood, carved with designs, including a human face, and decorated with pigment: Oceania, Melanesia, Papua New Guinea, Gulf Region, 19th century.

Masked rituals were a celebration for the whole community. Preparations such as constructing the masks, growing crops and raising pigs for feasting could take months or even years. But while they were mainly a celebration, masked rituals also had a more serious side: the welcoming and appeasing of spirits. The rituals also served to persuade the spirits to support the community’s human efforts and endeavours. Masks could allow dancers to be temporarily possessed by spirits and lose their own personal identities.

The hevehe ceremonies took place on a cycle that lasted between 7-20 years, and were a very important part of community life. Their main purpose was to pacify and drive away any angry spirits from the community's land, often back into the sea.

The cycle began with the construction of a new ceremonial longhouse. Inside, over a number of years, the massive hevehe masks would be made in secrecy, with public feasting and gift-giving celebrating different stages of progress. When all of the masks were finished, a new door was made in the longhouse for the masked figures to finally emerge for a month of celebrations.

Above: A group of Elema people standing in front of a thatched roof men's house, all wearing plant fibre skirts, neck ornaments, and nose ornaments, with several people holding hevehe (masks); Purari Delta, Papua New Guinea. © The Trustees of the British Museum (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

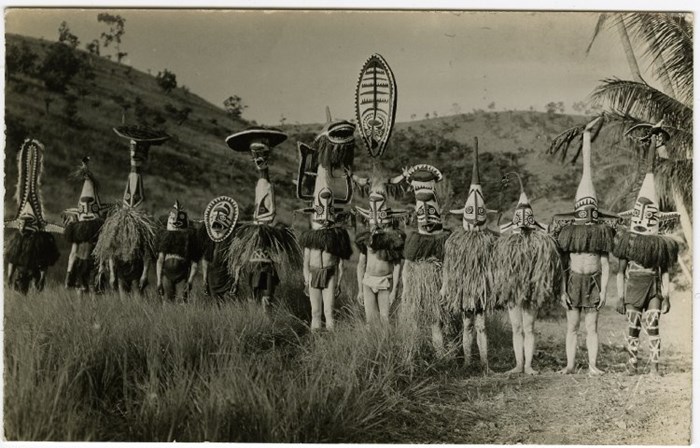

Eharo masks like the three in the Museum's collections were worn before and during the emergence of the sacred hevehe masks as less serious, un-sacred, more humorous accompaniments. Anthropologist FE Williams records them as being called ‘dance head pieces’, or ‘things of gladness’.

Some eharo masks represent totemic spirits associated with individual clans. Others embody comic social commentary, representing characters or humorous figures from oral traditions, such as lecherous old men or uninitiated boys. The construction of eharo was less secretive than the hevehe and could be observed by women. The audience knew that there were men beneath the masks, for instance, although their bodies were often hidden under thick fringes of plant fibres or barkcloth strips, with a variety of cloth wraps and body paint, as can be seen in a series of photographs held by the British Museum.

Above: Postcard showing thirteen young men in a grassy landscape wearing eharo masks, plant fibre shoulder coverings, cloth wraps and body paint; Purari Delta; Papua New Guinea. © The Trustees of the British Museum (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Other photos of young men wearing eharo masks can be found on the British Museum collections database by searching ‘Gibson Photo, Port Moresby’.

Eharo masks were made and worn by young men from neighbouring villages at the request of the village hosting the ceremony. As they entered the settlement where the ceremony was due to take place, women threw shredded coconut at the masks' wearers to neutralise their seductive powers. Once rendered harmless, the masked figures would dance with the women to entertain the audience. Generally dancing in pairs, they would swoop though the crowds, where they would play drums and sing and dance amongst the crowd.

Masks would usually be burnt at the end of the month-long ceremony, so surviving examples are rare. In the first two decades of the 20th century, European missionaries and traders caused massive social upheaval by confiscating or publically destroying sacred objects and eliminating traditional cultural practices. Masks like these survive because they were collected by anthropologists in the field, or sent home to Europe and America by missionaries as evidence of their zealous conversions.

All three masks are made of barkcloth stretched over a split-cane frame, sewn together with vegetable fibre and coloured with white, red and black natural pigments. Across the Pacific, barkcloth is a symbolic and often high status non-woven textile made from the pounded inner bark of either the dye fig or paper mulberry tree.

The masks show great vitality, originality and diversity in form, shape and scale, with abstracted and stylised facial features. They have a great presence, power and dynamism lying latent in their wide staring eyes, gaping mouths and sharp teeth. They are reasonably light-weight, which meant they could be worn for long periods by physically active performers, although the wearer’s vision would have been extremely limited.

Above: Mask A.1951.372, a tall, narrow, helmet-like mask.

Two of the three masks incorporate long projecting structures that resemble, or may represent, the fin or snout of a marine creature, decorated with a black serrated pattern. A.1951.372 is a tall, narrow, helmet-like mask reaching 84cm high. Like the fin or snout, the eyes and mouth are bordered with serrated black teeth or abstract shapes: those around the eyes extend upwards to partially encircle the forehead ornament. Rounded, thin wooden teeth surround an open triangular mouth that projects slightly forwards below the nose. The base of the mask is supported on a projecting wicker frame bound with twine, from which a grass fibre fringe would originally have hung.

Above: Mask A.1951.371, a larger, more ornate mask.

Above: Mask made of barkcloth, pigment, wicker, cane and vegetable fibre. © The Trustees of the British Museum (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0).

A.1951.371 is larger and more ornate in structure and decoration, with a pointed cone on the top and projecting fins that point sideways and backwards. Hanging from the fins are the remains of thin barkcloth streamers, which are striped and painted with red pigment. The pointed snout extends forwards with a bristling forest of needle-thin wooden teeth, about the scale and sharpness of cocktail sticks. Like A.1951.372, this mask is supported on a projecting wicker frame bound with twine, from which a grass fibre fringe would originally have hung.

Very similar examples to mask A.1951.371 exist in other museums, including the British Museum and the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa in Wellington, New Zealand.

Above: Mask A.1951.373, a triangular, visor-like mask.

A.1951.371 has a triangular, visor-like face that points down from a domed headpiece and is covered with at least two different types of human hair in tight brown and black curls. As with the other two masks, the face is again surrounded by a serrated black border with black fishhook-like shapes descending below the eyes.

A similar-shaped mask held by Fairbanks Museum and Planetarium, St Johnsbury, Vermont, has been identified as a hornbill or a crocodile.

The three masks in the Museum collection are from a group of over 270 world cultures artefacts received as gifts between 1949 and 1953 from the collections of the Wellcome Historical Medical Museum. The pharmacist and entrepreneur Henry Wellcome amassed an enormous collection of very diverse anthropological material relating to physical and spiritual health and well-being of different cultures throughout the world. Following his death, the collection was distributed to several different museums.

Wellcome acquired his material from a vast range of sources, including ethnographic dealers, so there is little information or provenance for some objects. Receipts in the Museum's archives indicate that the masks were acquired at auction in 1924 and 1925 and fully accessioned into the Wellcome Historical Medical Museum in 1936, but sadly no further mention is made of where, when, how or by whom the masks were acquired, made or used.

Beier, U. and Kiki A.M. Hohao: The uneasy survival of an art form in the Papuan Gulf (Thomas Nelson (Australia) Limited, Melbourne, 1970).

Newton, D., Art Styles of the Papuan Gulf exhibition catalogue (The Museum of Primitive Art, New York, 1961)

Welsh R.L., Webb V-L, and Haraha, S, Coaxing the Spirits to Dance: Art and Society in the Papuan Gulf of New Guinea exhibition catalogue (Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, 2007)

Williams, F. E., The Drama of Orokolo: the social and ceremonial life of the Elema (Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1940)