Key in a search term below to search our website.

Key in a search term below to search our website.

The story of this 100-year-old planetarium provides a fascinating glimpse into the history of science interpretation, as well as a behind-the-scenes peek into early 20th century museum politics.

Date

1913

Made in

Munich, Germany

Made by

Michael Sendtner

Made from

Glass, metal

Dimensions

Height 230cm, length 151cm, depth 151cm

Museum reference

On display

Earth in Space, Level 1, National Museum of Scotland

Did you know?

Our orrery is one of five created by Sendtner. A pair in the Deutsches Museum demonstrate the Ptolemaic system, in which the planets revolve round the earth, and Copernican, or solar-centric, system. The other two can be found in the Cranbrook Institute in Michigan and Franklin Institute in Philadelphia.

An orrery is a mechanical model that demonstrates the motion of the planets, moons and sun in the solar system. Planetary models, or planetaria, had existed since the time of the Ancient Greeks, but the first modern orrery, which also showed the earth’s rotation, was created in 1704 by clockmakers George Graham and Thomas Thompion. Their design was then passed to the London instrument maker John Rowley, who presented a copy to his patron, Charles Boyle, 4th Earl of Orrery, after whom the device came to be named.

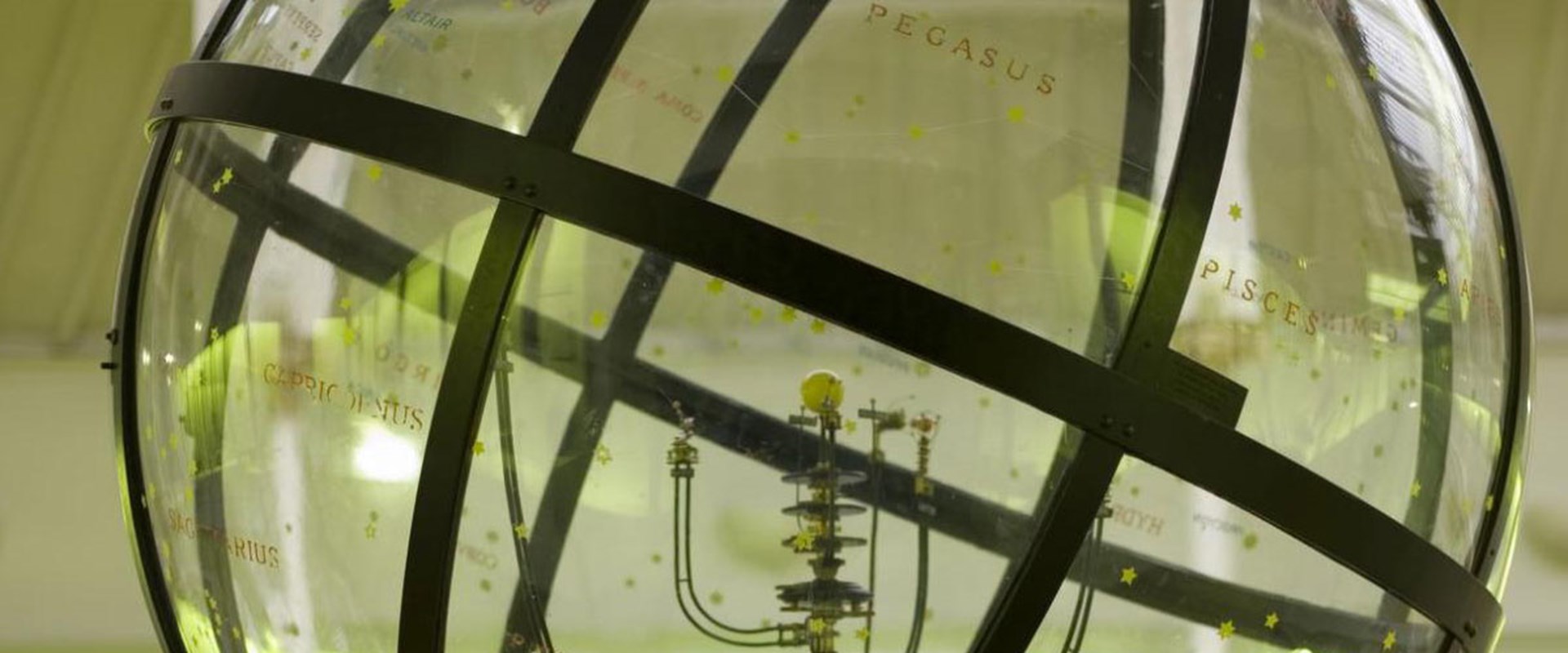

The National Museums’ orrery shows the eight planets of the solar system with their satellites revolving round the sun. It is encased in a glass globe painted with the chief constellations.

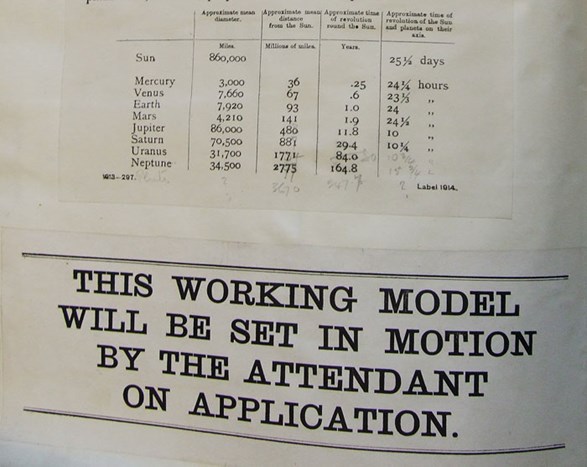

Made in 1912-13, the orrery does not include Pluto, which was not discovered until 1930. However, since Pluto was demoted to the status of ‘dwarf planet’ in 2006, the orrery is up-to-date again.

Above: Record copy of the original museum label for the orrery. Note that Pluto has been pencilled in! Click on the image to see the full label.

The sizes of the planets and distances between them are not to scale, as this would be impossible within the confines of a gallery. Instead they are based on logarithms, a method of simplifying calculations involving very long numbers. The rates at which the planets and satellites rotate are proportional to the actual rates.

Our orrery was commissioned in 1912 by Alexander Galt, Keeper of the Technological Department at the Royal Scottish Museum, now the National Museum of Scotland. The maker was Michael Sendtner of Munich, who had previously supplied two models to the Deutsches Museum, also in Munich.

The production of the orrery, however, was far from straightforward. A series of letters from Galt to Sendtner documents the increasingly frustrating process, which appeared to test the curator’s ability to remain polite in the face of escalating incompetence. We can only guess at the responses he received from Sendtner as these have not be retained. However, judging by Galt’s tone, they were far from satisfactory.

From the start, Galt quibbled over the technical specifications for the planetarium, taking a year to finally proceed with his order.

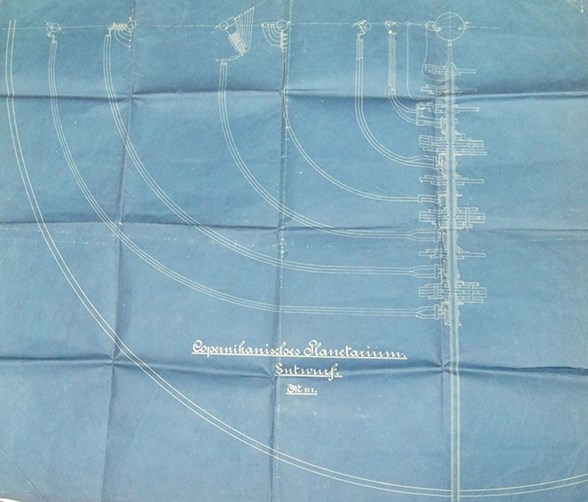

Above: The original blueprint of the orrery sent to Galt by Sendtner.

By March 1913, production of the orrery was running late: “Will you please say when it is to be despatched as three months have already elapsed?” Galt wrote. A month later, it still hadn’t arrived.

The next letter, dated 2 July, relates a tale of woe. The orrery had finally been delivered, but, possibly due to careless packing, “could not be set in motion.” In addition, “The moon appears to revolve round the earth the wrong way” and “Most of the spindles are too small for the bearings, leading to considerable looseness”.

On 11 July, the orrery was returned to Sendtner, with further complaints that “the stars are in the right position relative to each other but that they are painted on the wrong sheets of glass.”

Worse was to come. The orrery was damaged on its return journey to Germany – not, Galt noted tartly, through any fault of his – and Sendtner’s quote to fix it was too high. In addition, it still didn’t work “in accordance with astronomical truth”: “Strict accuracy is of the first importance in a Museum model,” Galt pointed out sternly.

“Strict accuracy is of the first importance in a Museum model.- Alexander Galt

By the end of November, the orrery had been returned to Edinburgh, but with “the constellations… still inaccurately placed.” “Will you please say what is to be done?” Galt asked plaintively.

Above: A photograph referenced in Galt’s letter of 8 Aug 1913, showing how the constellations all need to be moved over. There's also a spelling error in Gemini, Pullux for Pollux, whilst the constellation labelled Libra just below Orion is actually Lepus.

In December things were no better, with Galt despairingly drawing a diagram to show how the stars should be placed. And then, on 7 January 1914, a miracle: “The painting of the stars is now quite satisfactory and the account may be paid.” The orrery was complete.

You can see Galt’s letters here, followed by the orrery’s entry into the Museum’s object register.

19 June 1911 | 13 Oct 1911 | 2 Nov 1911 | 30 Oct 1912 | 14 Nov 1912 | 18 March 1913 | 23 April 1913 | 2 July 1913 | 2 July 1913 cont. | 11 July 1913 | 8 August 1913 | 8 August 1913 cont. | 1 Sept 1913 | 1 Sept 1913 cont. | 17 Sept 1913 | 1 Oct 1913 | 14 Oct 1913 | 31 Oct 1913 | 29 Nov 1913 | 9 Dec 1913 | 29 Dec 1913 | 7 Jan 1914 | Accession register record

Sadly, despite Galt’s best efforts, the orrery remained prone to sticking. During the twentieth century it was extensively overhauled at least twice. After dismantling it completely and cleaning and treating each of its 500 parts in 2001, our Conservation department decided that it was not in the orrery’s best interests to replace any further parts and that it would be safer to leave it as a static object.

Above: The orrery in the Earth in Space gallery at National Museum of Scotland. Photo © Jenni Sophia Fuchs.

Now taking pride of place in the Earth in Space gallery, a hundred years after its creation, the orrery still inspires us to visualise the vastness of space and the movements of the solar system, its perfectly aligned planets remaining testament to the persistence of Dr Alexander Galt!

You can read writer and comedian Chella Quint's blog post about the orrery here.