Key in a search term below to search our website.

Key in a search term below to search our website.

Edinburgh in the late 18th and early 19th century was not a pleasant place to live. It was crowded, unsanitary and unhealthy. Those who could afford to live outside the city centre or Old Town in the expanding suburbs. Others had moved out of the crowded tenements into the New Town as it was gradually built from the 1760s. But this exodus into more salubrious dwellings was counteracted by the influx of economic migrants coming into the city in search of a living.

Among the incomers to the city was a population of people seeking employment. Late 1827, two Irish migrants, William Hare and William Burke, met whilst living at the lodging house of Hare's wife, Margaret Laird, in Tanner's Close. Tanner's Close was located in the West Port, near the busy Grassmarket. Margaret Laird and William Hare were poor but fairly secure financially in comparison to the itinerant workers or pensioners who lodged with them.

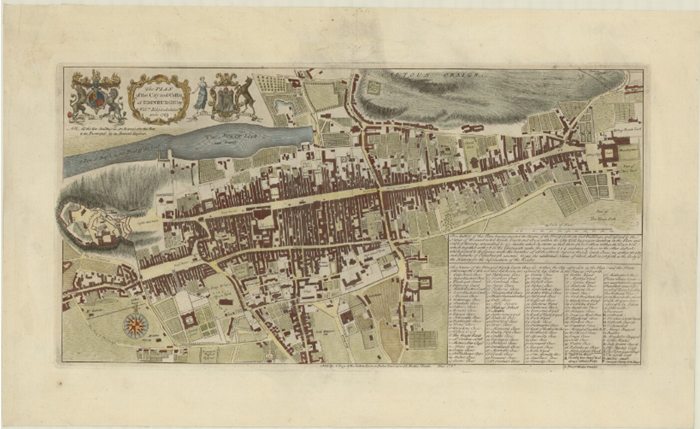

Plan of the city and castle of Edinburgh / by Willm. Edgar architect anno 1765, hand coloured. Image from the National Library of Scotland.

William Burke had been a worker in the construction of the Edinburgh and Glasgow Union Canal and subsequently developed a shoe-mending business. However, Burke and Hare were always looking for opportunities to supplement their income and this is what led them on their murderous enterprise to supply bodies to Dr Robert Knox, for use in his anatomy school in Edinburgh. Find out more about the story of Burke and Hare and the West Port murders in our Arthur’s Seat Coffins story. By looking at what life was like in Edinburgh at the time of Burke and Hare, we can better understand what drove them to do what they did to better their lot.

Prior to the development of Edinburgh’s New Town, the size and layout of Edinburgh’s Old Town affected how people lived their lives. It was characterised by very poor street lighting and crowded city streets, and closely packed tenements. The narrow spaces in the city’s numerous closes and wynds meant people spent more times outdoors, at inns and taverns, and in public spaces. Before architect James Craig’s development of the New Town, Edinburgh’s city centre consisted of a space measuring just around 900 by 500 metres.

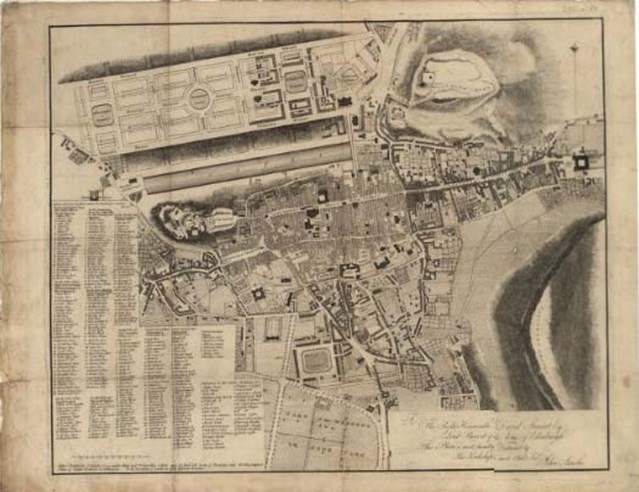

John Ainslie's plan of the City of Edinburgh, c.1780 showing the Old and New Towns. Image from the National Library of Scotland.

A painting of an interior with a family group, By an artist unknown (H.OD 86).

Scottish cities expanded so much between 1760 and 1830 that the rate of growth proved overwhelming for existing sanitation structures. People in the Old Town of Edinburgh lived near one another, and the insanitary conditions helped spread diseases. Often, families lived in one room (sometimes more than one family lived in one room), and there were no separate toilets or bathrooms, besides a communal chamber pot.

Brown rat specimens in the drain diorama at the National Museum of Scotland (Z.DT.139).

Between 1791 and 1831 the population of Edinburgh, and the neighbouring Port of Leith, doubled in size from 80,000 to 160,000. The building of new homes did not keep pace. The creation of the New Town also had a detrimental effect on the hygiene of the Old Town, as two of the three water pipes that supplied the city were diverted to the former, which even had the luxury of modern sewers.

Edinburgh had water wells throughout the city from which water could be drawn. There were six wells in the Old Town, which piped in water from the reservoirs and streams from outside the city. Water pipes were originally made of wood but were later replaced with lead piping. In the 18th century, the water supply from the wells was restricted and many people had to buy water from the numerous water street sellers. However, these wells often provided only restricted access to water, and although water could be piped into the wealthiest homes, many people still had to buy water from the numerous water street sellers. The water supply to Edinburgh was improved during the 19th century.

Bourdalou or lady's earthenware chamber pot of earthenware by Hamilton Watson and Co, c. , Prestonpans, Scotland, 1817 – 1834 (K.2002.633)

Sewage remained a nuisance in the Old Town and from 1822 cleaning was made the responsibility of the police. This was not the constabulary, but instead were separately employed and very poorly paid scavengers, many of whom were impoverished migrants from Ireland. Their job was to remove foul matter from the streets, where it was still thrown by householders each night. Waste being thrown out of tenement windows is where the infamous expression of 'Gardyloo!' comes from, derived from the French gardez l'eau, 'watch the water'. The mostly organic matter had value, and much of it was either composted or carted outside of the city for use as manure.

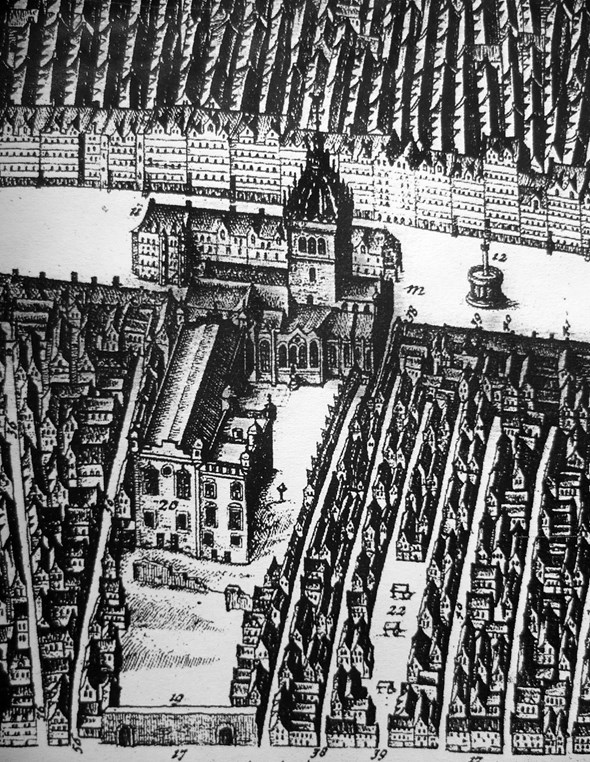

Edinburgh Old Town in the 1760s.

The Nor’ Loch, now Princes Street Gardens, was also heavily polluted with sewage, rubbish and was a general dumping ground for all people and trades. It is unlikely it ever served as a source of drinking water for the people of Edinburgh. Nor’ Loch was subsequently drained to make way for the building of the North Bridge and the construction of the railway and the development of Waverley Station.

Edinburgh Castle with the Nor Loch in the foreground before it was drained, c. 1690. Part of an engraving by John Slezer.

Some Edinburgh residents kept livestock in burgage gardens to supplement their income and in the West Port there was a tradition of keeping pigs. The animals were free to roam the streets which only added to the mess that already existed and this was also a great nuisance to the residents of the area.

One article from The Scotsman, published in 1853, titled ‘ 'Inquiry into Destitution and Vice in Edinburgh', tells how:

“...the numbers of swine being kept by some families were immense – fifty or sixty, or even a hundred, might be found belonging to one man”.

The owners would feed their pigs food scraps bought from cooks and housekeepers and could make money from not only selling the pig but from selling the dung!

Oil painting of a Berkshire pig by William Shiels, early - mid 19th century (H.OD 100).

By 1800, although some local clothing manufacture survived, much of the clothing worn by Scots was commercially produced. Clothing was increasingly imported from elsewhere in Britain or from abroad and purchased from market stalls or shops throughout the Old Town.

A pair of old miners’ leather shoes from the early 19th century, like those worn by the people pf Edinburgh’s Old Town. (T.1856.108.10.A)

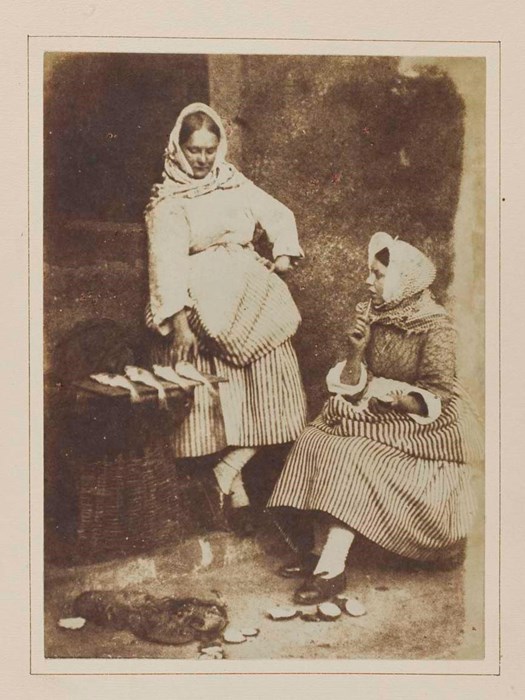

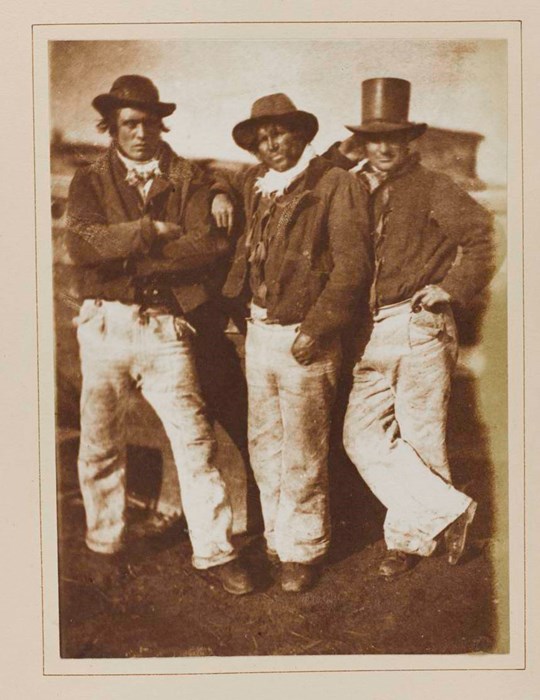

Few examples of the type of clothing worn by ordinary people of the time survive. Most people recycled or repurposed their clothes and photographs and illustrations can give us an idea of what they wore. For the wealthy, it was a different story as clothing was under less stress and survived better and that is why there are many fine examples of the clothing that they wore in the museums’ collections.

Woman's black net dress with a floral design in black silk thread, part of an ensemble with cotton under dress c. 1810 – 1820. (A.1963.459)

Man's tartan suit with gilt metal buttons in a Royal Stuart variant, c. 1830 (A.1994.102 A).

Working-class people of Edinburgh could not afford meat and fish, so ate porridge (not just for breakfast), as well broths made from oats, grains, pulses, and potatoes, supplemented with milk, ale, kale, and butter. Oats could be made into a variety of cheap and filling dishes flavoured with whatever ingredients were on hand. Wheat only became more readily available to the Scottish masses in the 19th century. Wealthier Edinburgh residents could afford to buy meat, fish, and fruit from Edinburgh’s several bustling markets.

Photograph of Edinburgh’s Grassmarket by William Donaldson Clerk c.1860 from the National Galleries of Scotland.

Food was purchased from street sellers and markets. Their locations are reflected in many of the city’s street names: Fleshmarket Close, Fishmarket, Grassmarket (where cattle were bought and sold), and between 1823 and the 1860s Market Street, where a vegetable market was located. Fish and shellfish was brought in from the nearby ports at Newhaven and Leith and was sold by ‘hucksters’ and fishwives in the streets. Street sellers included people who sold salt, oysters, fish, water, milk, and many other foodstuffs.

Salt print depicting Jeanie Wilson and Annie Linton, two Newhaven fishwives from a volume of salt prints by David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson, 1843 - 1847 (D.2014.2.85)

Salt print depicting Alexander Rutherford, William Ramsay and John Liston, three Newhaven fishermen, from a volume of salt prints by David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson, 1843 – 1847 (D.2014.2.91)

As well as the markets and sellers mentioned above, another 18th century market existed on the High Street (now Royal Mile) until it was demolished in 1802. It was situated in a row of tenement buildings to the north of St Giles’ cathedral. This market was known as the Luckenbooths and had been a place of commerce in the city since the 15th century. According to Walter Scott in the Heart of Midlothian:

"...the ‘little booths, or shops’ contained the stalls of ‘hosiers, the glovers, the hatters, the mercers, the milliners, and all who dealt with miscellaneous wares now termed haberdashers’ goods' ".

The High Street more generally was home to a variety of different shops selling food, clothing, books and household goods.

Detail from James Gordon of Rothiemay's map of Edinburgh 1647. The building beyond St. Giles is the row of open-fronted shops called the Luckenbooths.