Key in a search term below to search our website.

Key in a search term below to search our website.

Alexander Henry Rhind (1833–1863) was a pioneering Scottish archaeologist – his experience excavating prehistoric sites in Scotland informed his innovative work in Egypt. His early death meant that his importance has often been overlooked, but he deserves credit as the first experienced archaeologist to excavate in Egypt.

Portrait of Alexander Henry Rhind of Sibster, oil on canvas, by Alexander S. Mackay, 1874

Alexander Henry Rhind was born the son of a wealthy banker in Wick in the north of Scotland on July 26th, 1833. It was still early days in the development of archaeology, but Rhind’s interest was sparked by his studies at the University of Edinburgh. There he was taught that it was possible to learn about life in prehistoric times from ancient objects buried in the ground.

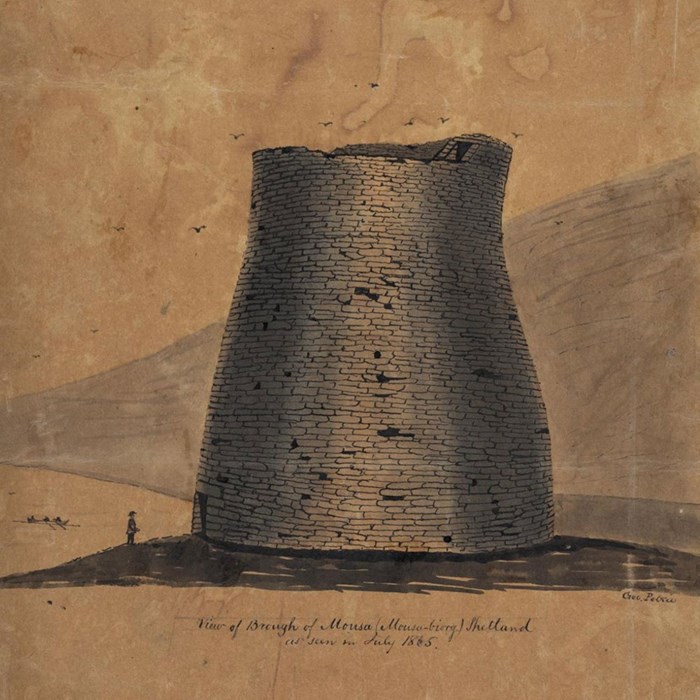

Pen and ink drawing of the broch at Mousa, Shetland, George Petrie, July 1865.

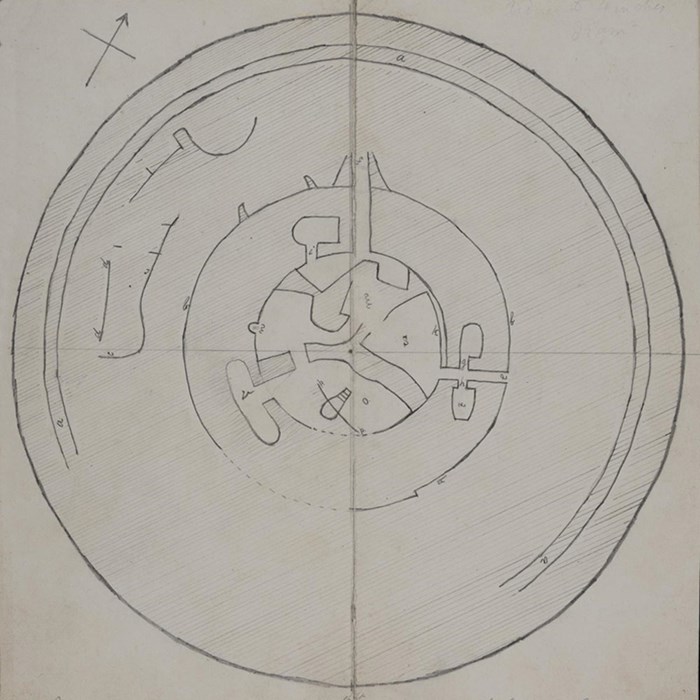

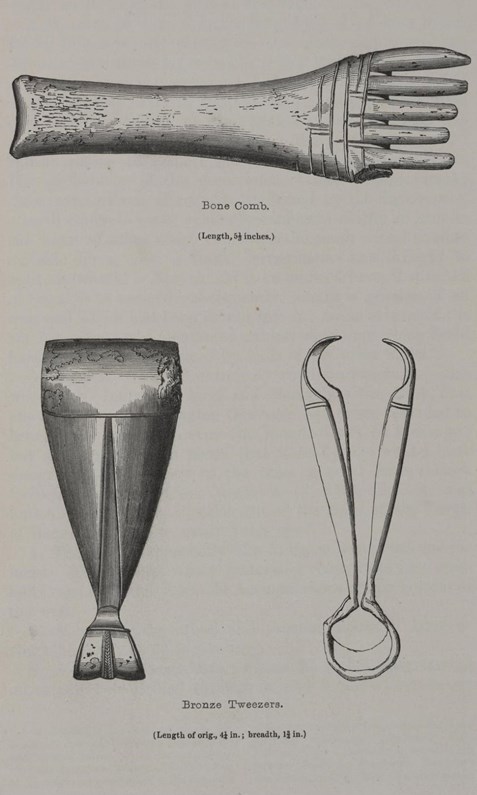

Henry became the first person to systematically excavate a broch, a Scottish Iron Age fortified building. Kettleburn Broch in Caithness was due to be demolished by a local farmer for agricultural land, but Henry persuaded him to let him excavate there first. His team dug carefully and methodically over three months and he recorded everything that was found, including tools, combs, and animal bones, which he donated to the Museum.

Hand-drawn plan by Alexander Henry Rhind of the ‘Picts’ House’ (broch) at Kettleburn, in the County of Caithness, 1853.

Illustration of a whale-bone weaving comb (X.GI 36) and bronze tweezers (X.GI 75) from Alexander Henry Rhind’s ‘Notice of the Exploration of a ‘Picts’ House, at Kettleburn, in the County of Caithness’ (1853).

When Henry was given permission to excavate in Egypt, he fully appreciated the great responsibility he'd been given. He set out with the objective of finding an intact tomb, so that he could record the exact locations where the objects were found. He hoped to better understand their uses and how burial practices changed over time.

Henry initially found a tomb belonging to a group of princesses that had been robbed in ancient times. Little remained, but it was probably the source of an extraordinary decorative box. Next to this, Rhind found the intact tomb he had been looking for.

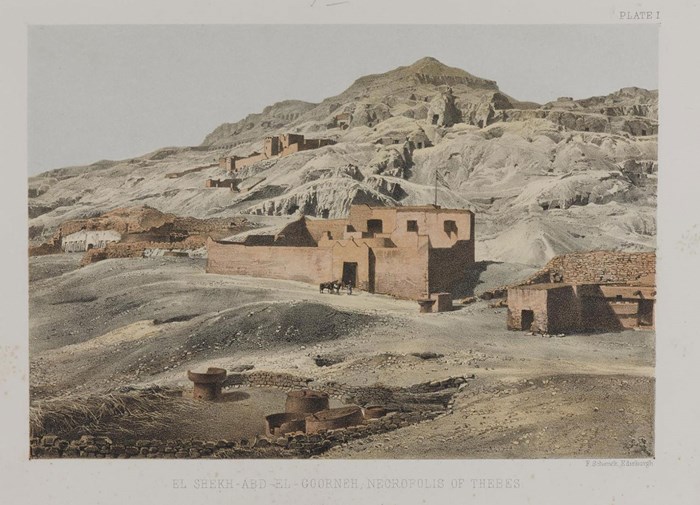

The Tombs of the Nobles and the house where Alexander Henry Rhind stayed during his excavations at Sheikh Abd el-Qurna, Theban West Bank (Luxor), from his book Thebes, Its Tombs and their Tenants, Ancient and Present (1862).

Watch this video to find out how the Rhind tomb, built around 1290 BC, was re-used over a period of 1000 years.

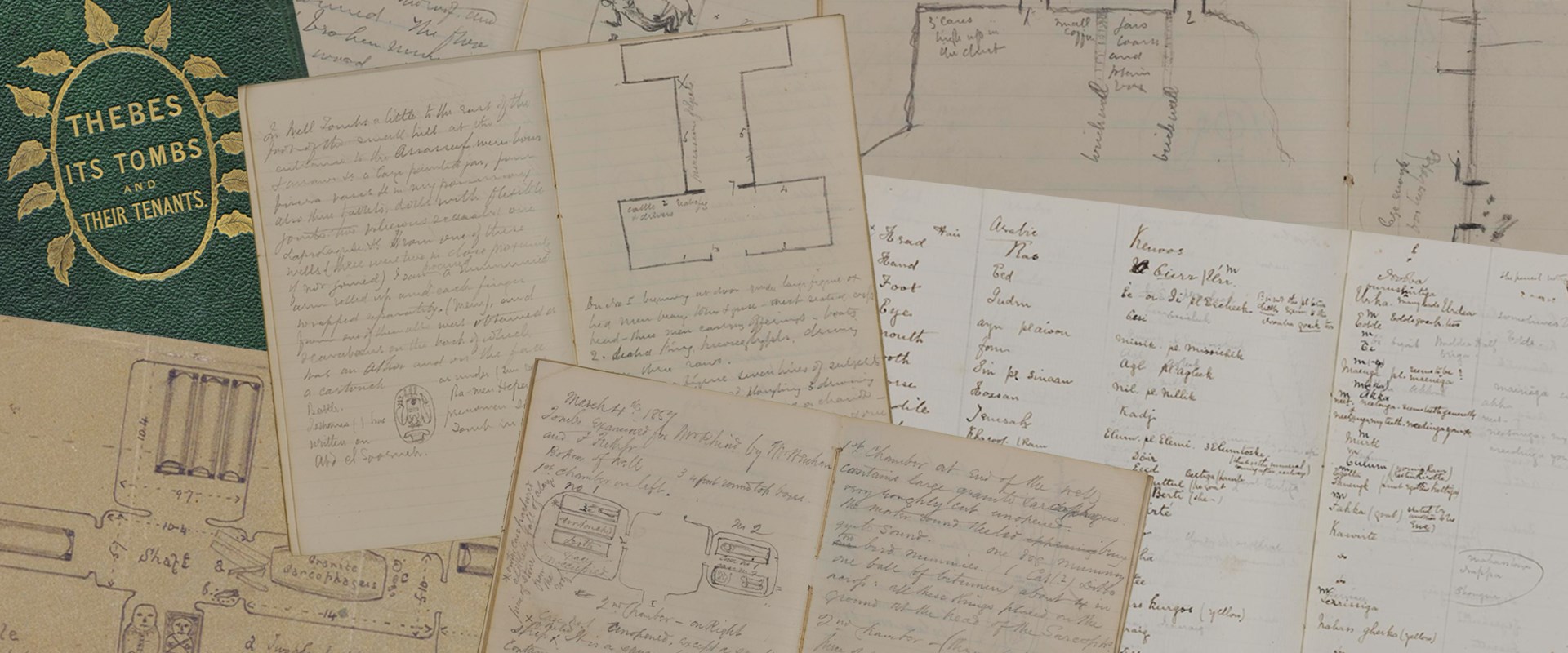

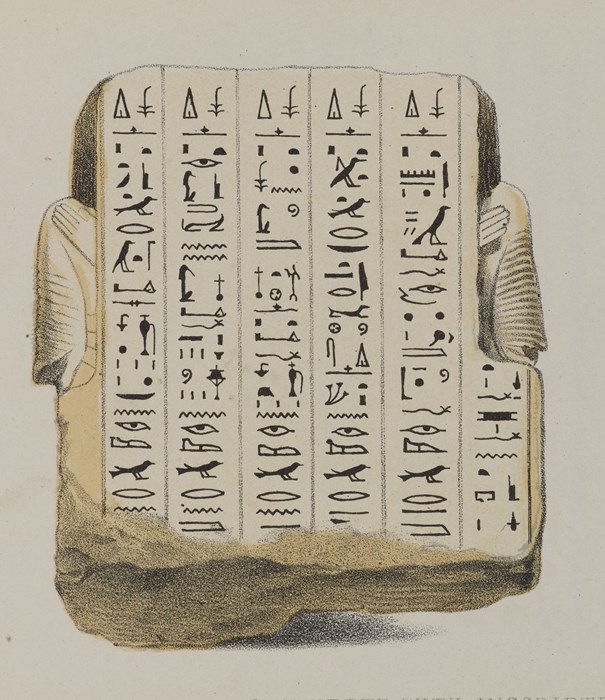

The Rhind Tomb, as it is now known, had originally been built for a Chief of Police in his wife around 1290 BC and then subsequently reused by other Egyptians for over a thousand years. It was finally sealed in the early Roman era with an intact family burial. He recorded and drew the exact locations of each object that he found and brought most of them back to the National Museum in Edinburgh. He published his findings in a book entitled Thebes, Its Tombs and Their Tenants. Because of his detailed records, we can still learn from the tomb today.

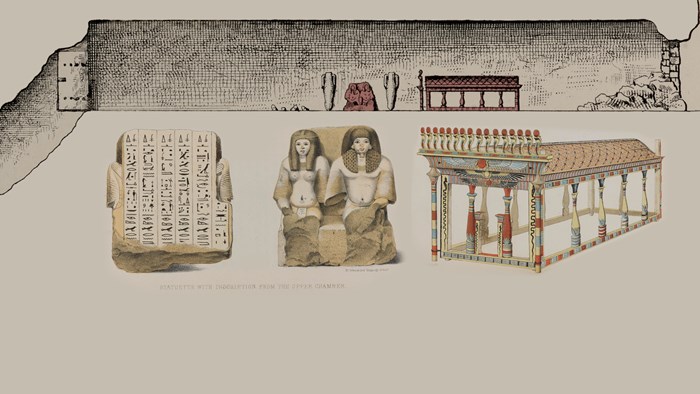

Section of the tomb plan and object illustrations from Thebes, Its Tombs and Their Tenants by Alexander Henry Rhind.

Illustration of the pair statue excavated by A.H. Rhind in the Rhind Tomb at Sheikh Abd el-Qurna, Thebes from his book Thebes, Its Tombs and their Tenants (1862).

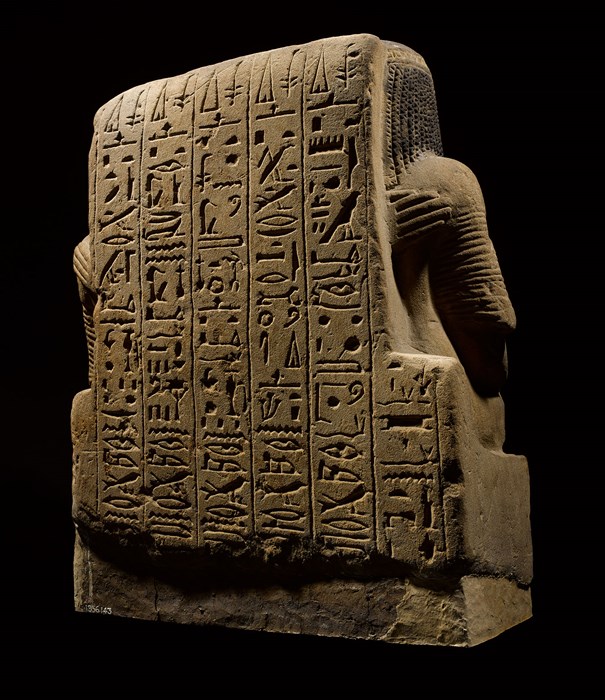

Pair statue in fine yellow sandstone of a Chief of Police (Medjay) and his wife, Sheikh Abd el-Qurna, Thebes, c.1322-1279 BC.

Illustration of the pair statue excavated by A.H. Rhind in the Rhind Tomb at Sheikh Abd el-Qurna, Thebes from his book Thebes, Its Tombs and their Tenants (1862).

Pair statue in fine yellow sandstone of a Chief of Police (Medjay) and his wife, Sheikh Abd el-Qurna, Thebes, c.1322-1279 BC.

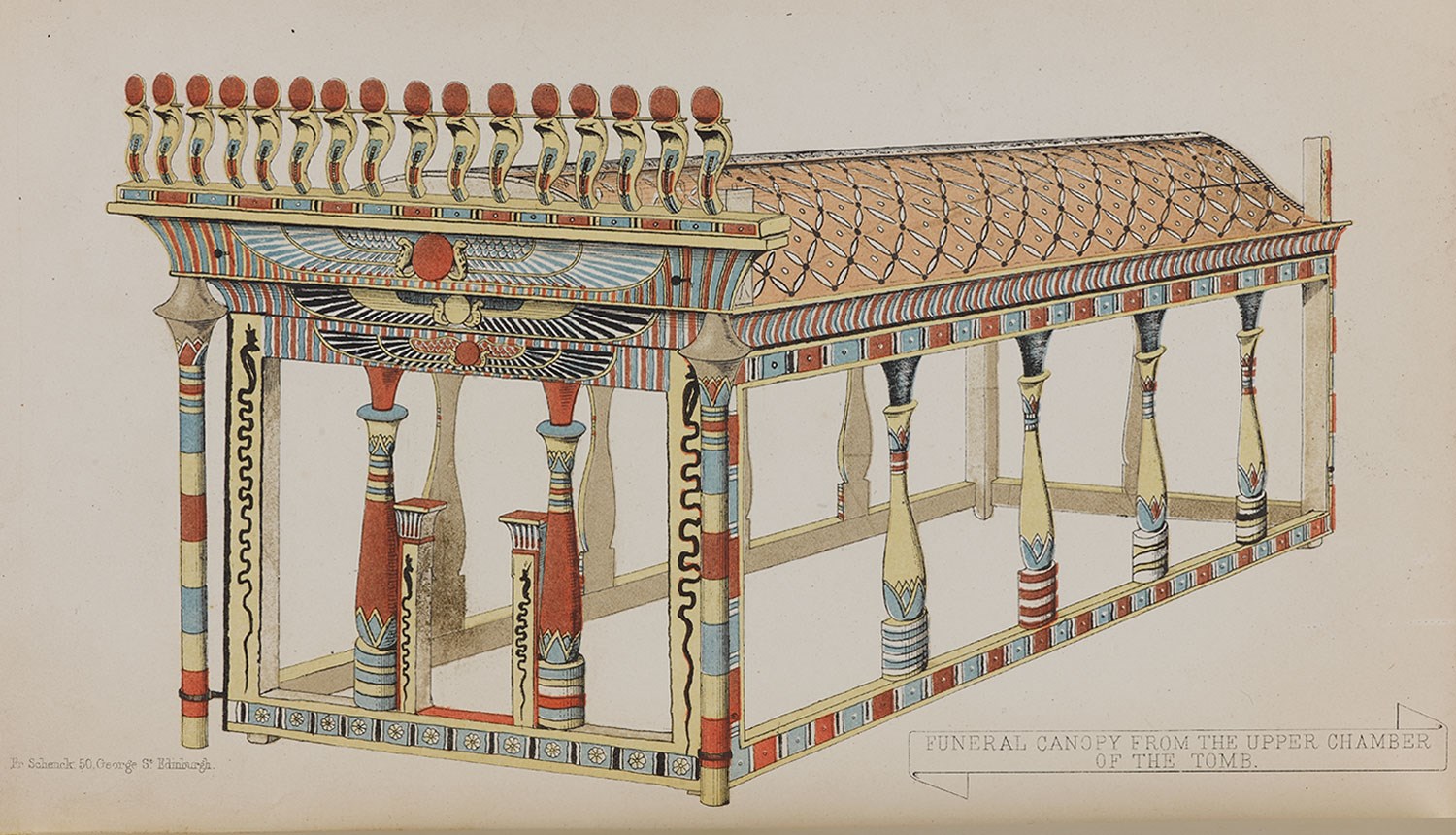

Illustration of a funerary canopy excavated by A.H. Rhind in the Rhind Tomb at Sheikh Abd el-Qurna, Thebes from his book Thebes, Its Tombs and their Tenants (1862).

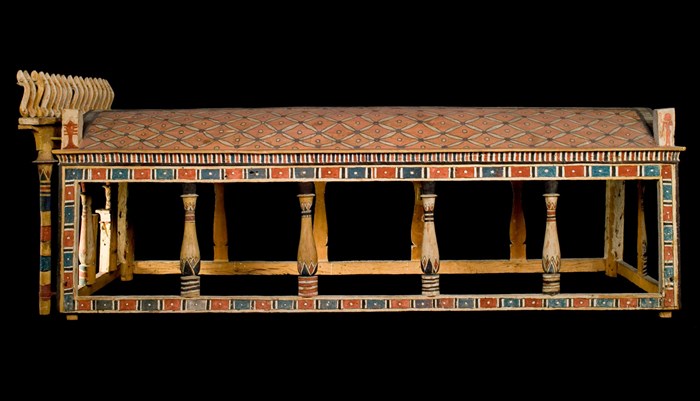

Funerary canopy of sycomore-fig wood with an arched roof and corner-posts inscribed for Montsuef, Sheikh Abd el-Qurna, Thebes, c.9 BC.

As Henry grew weaker from illness, he was no longer able to excavate, but he still worked just as eagerly – he studied different Nubian dialects and investigated how the course of the Nile had changed in relation to the monuments. On his final journey home from Egypt, Henry died in his sleep aged just 29.

His promising career was cut short and one can only wonder at the kind of impact Henry might have had if he had lived longer. He was beloved by his colleagues who had asked him to design the first displays at the newly formed National Museum. His work inspired Flinders Petrie, who popularised scientific excavation in Egypt, and he left a substantial legacy to the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, who hold lectures in his honour to this day. Many of the objects that he found are still in the National Museum of Scotland. Because of his detailed records, we can still learn from them today.