Restoring a rare Iranian tile panel

News Story

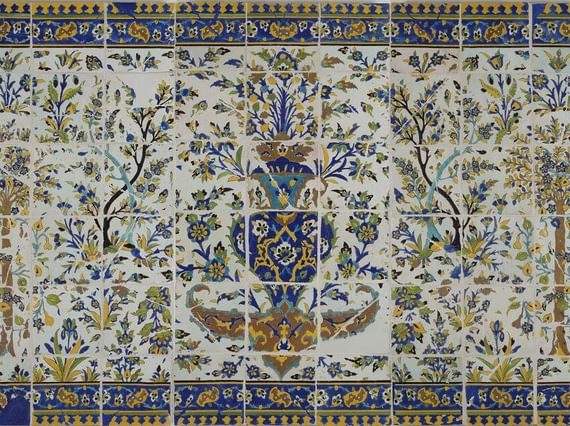

A rare ceramic wall panel illuminates the importance of gardens in 17th century Iran.

A rare survival

The tiles of this panel arrived in Edinburgh in October 1899. It was a rare and important acquisition for the museum.

A complete Panel, with its border, of very fine Persian wall tiles, enamelled and decorated in polychrome with conventional and floral design, from the Hammam (bath) of the Haft Dast Palace at Ispahan […].

Director's annual report, 1899

In Iran, the tiles had been packed in four crates, which were shipped by the Scottish firm Messrs Hickie, Borman & Co. We do not know what staff at the museum thought when they faced the task to assemble the 114 tiles into one panel. The tiles were not only several hundreds of years old, but they also came from a place with which they were likely unfamiliar.

The symmetry of the scene might have helped them. A more important clue to resolve the jigsaw, though, would have been the fact that the blue border tiles have a small part of the pattern in the white central field. We can only imagine how tile by tile the garden scene would have emerged before them.

Isfahan in context

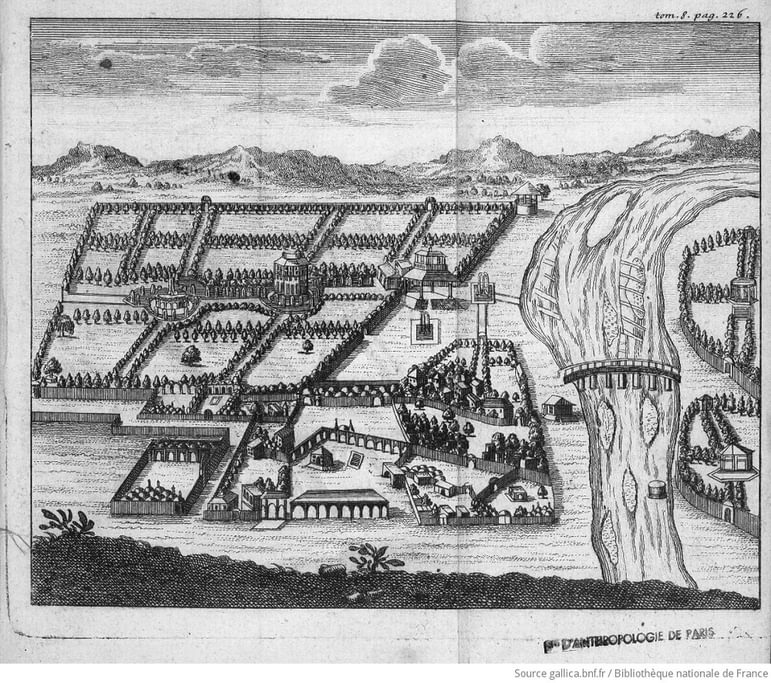

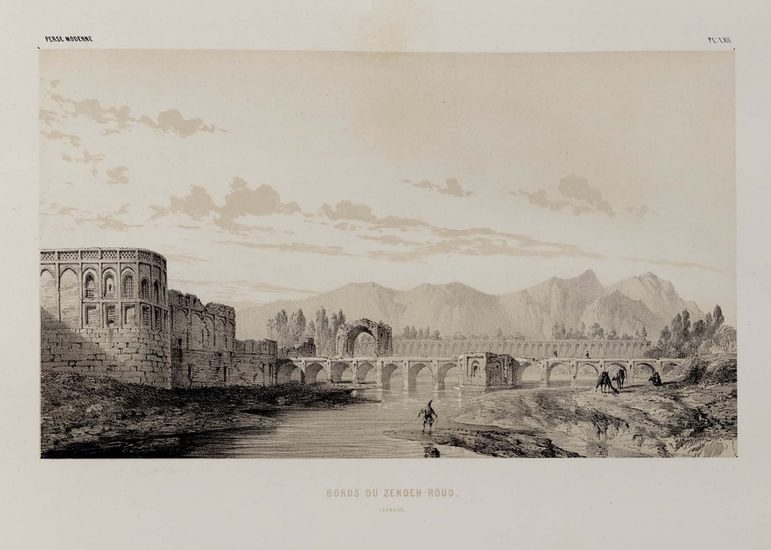

This tile panel and its beautiful garden depiction is more than 350 years old. It's said to have embellished a bathhouse (hammam) belonging to the royal Haft Dast palace in Isfahan, Iran. The palace was a suburban retreat, originally built for the Safavid ruler Shah Abbas II (who reigned 1642–66). The palace was located in the pleasure garden Sa’databad (meaning Abode of Felicity) on the southern bank of the Zayanda River.

In the middle of the 17th century, Isfahan was the capital of the Safavid empire, a cosmopolitan city and global trading hub. Merchants from east and west, north and south exchanged their commodities for goods produced in and around Isfahan.

Fifty years earlier, another ruler of the Safavid dynasty, Shah Abbas I (who reigned 1588–1629), had laid the foundation for this prosperity when he transformed the old city into a modern metropolis. He oversaw the building of the famous promenade, Chahar-bagh, which means Four Gardens. It's still a must-see of a visit to Isfahan today. The Chahar-bagh promenade connected the shah’s city palace with an enormous royal garden on the other side of the Zayanda River. This promenade was similar to Edinburgh’s Royal Mile, just much longer (4 km) and much wider (47 m). It was lined with rows of trees, pools, flowerbeds and coffee houses. This made it a favourite public space for Isfahan’s citizens to meet and spend time together.

A place for enjoyment

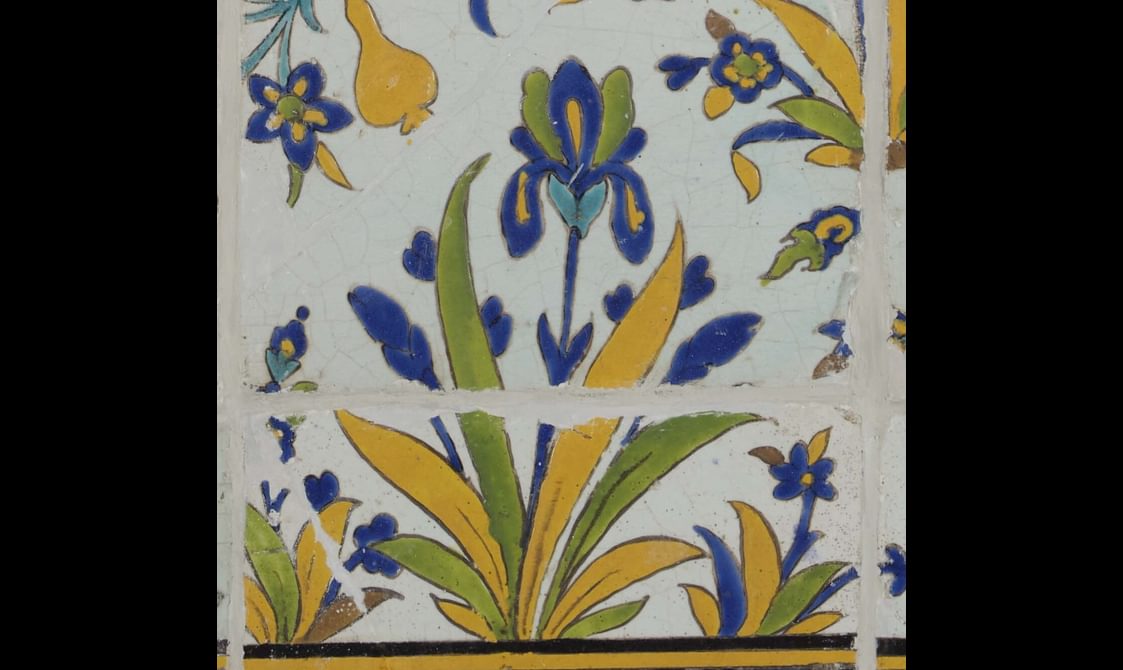

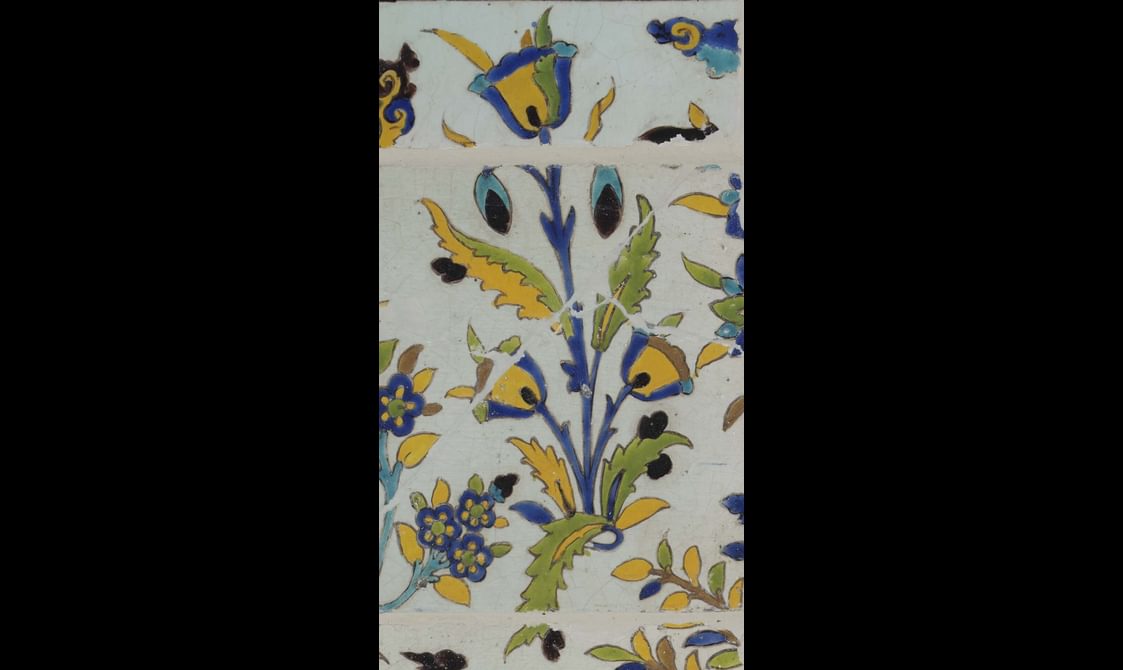

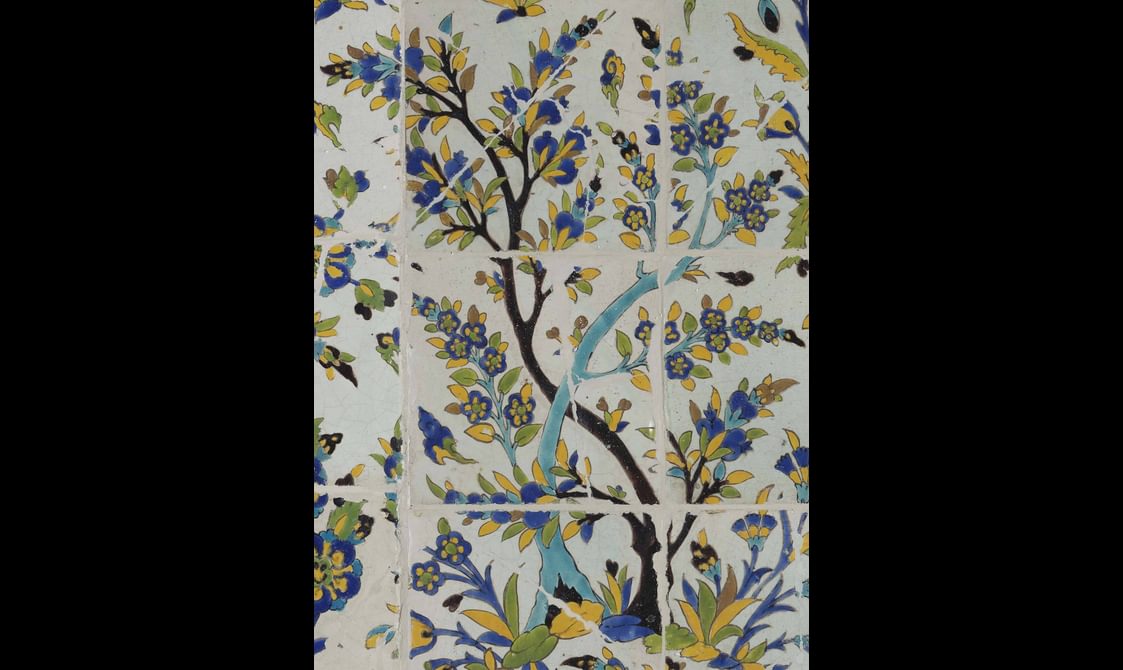

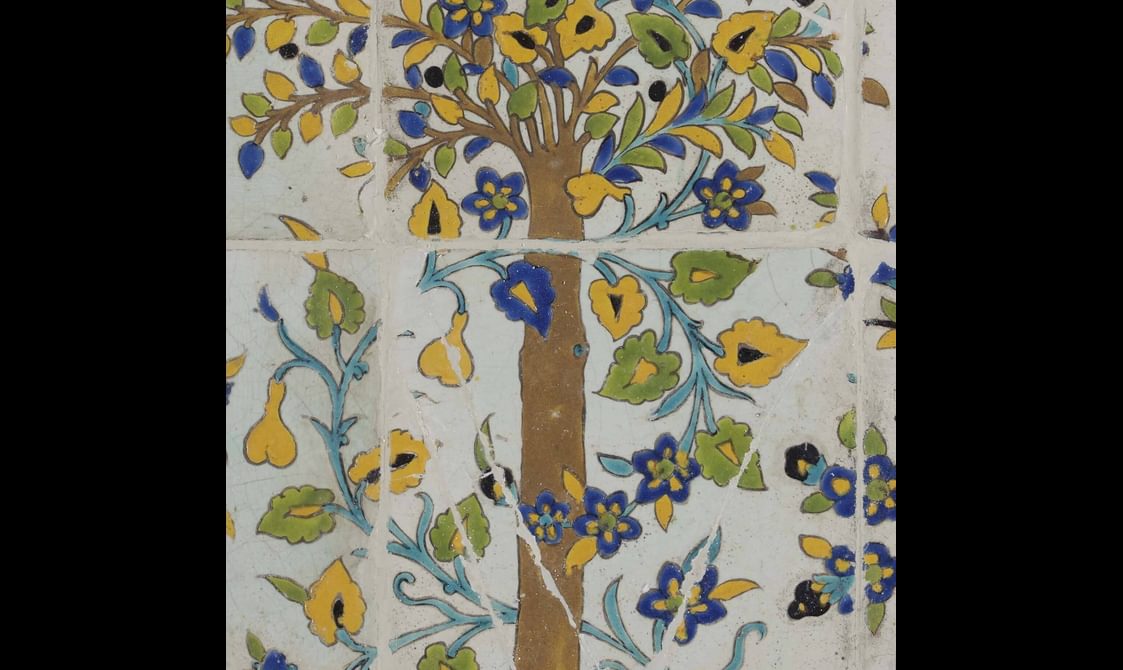

It's quite unusual to see a garden scene unfold over more than 4 metres and 114 colourful ceramic tiles. This panel shows a cultivated garden where people would come for their pleasure, to enjoy the abundance of life and listen to the murmur of running water. The central position of the flower vase points to the importance of water for any form of life. This message is repeated in the oval, blue-coloured ornaments on both sides of the vase. The trees, which fill the remaining space, remind us of the cooling shade they provide to other plants and people with their leafy crowns from the scorching sun.

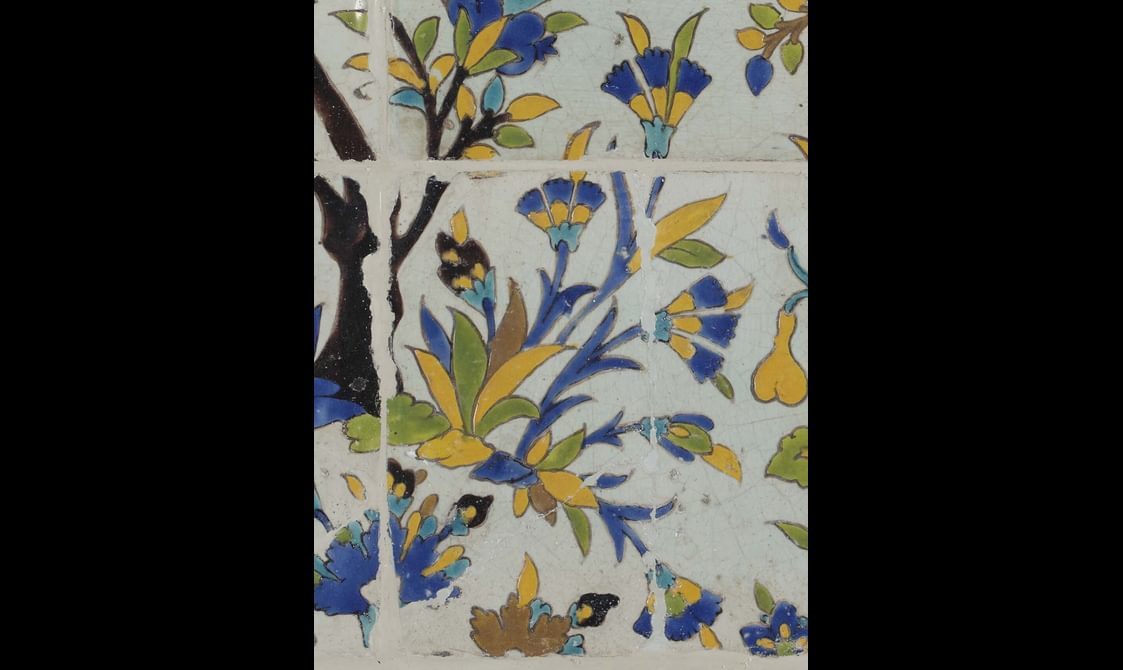

A closer look at the scene reveals the range of flowers growing in this garden: carnations, irises, poppies and possibly mallows. It might take a while to identify them due to the colours used. The artisans created every single element of the scene by using only four tones: yellow and green, and different shades of brown and blue. Delicate pomegranate trees appear left and right of the central flower vase. Their branches bend under the weight of the fruits they carry. However, watch out here! The pomegranates are painted in a deep blue, not in a red shade as one might expect.

Image gallery

Two trees stand out because of their tall straight trunks and round leafy crowns. While these two trees might be beautiful to look at and provide much needed shade, they do not bear fruit. Gardeners therefore often planted fruit-producing climbers next to trees. On the tiles, gourds are painted growing around tree trunks and into their crowns. Some of the vines have already fruited, while others still show flowers. The painters chose to depict this horticultural practice that was important at the time.

Image gallery

The symbolism of gardens

Garden palaces were where Safavid rulers could demonstrate their absolutist power. Following a strict ceremonial protocol, in them they would receive and host large numbers of foreign dignitaries and guests. On these occasions, the shahs would personally preside over the feasts and entertainments. These included multi-course meals accompanied by sherbets, wine, music, dance and fireworks.

The choice of garden settings as venues for royal receptions developed from the idea that Iranians had about the role of their kings. Iran has an arid climate, and the cultivation of the land was dependent on complicated and labour-intensive irrigation systems (qanats).

To maintain these qanats, a strong king was needed. Iran was therefore imagined as a walled garden with the king as its gardener: the walls protect the garden, while the water channels that cross it, make its plants a lush green. This imagined space has many flowers filling the air with their delightful fragrances, as well as an abundance of fruit-bearing trees.

This idea of kingship was also the inspiration for the garden scene on the tile panel. The white central field represents the garden. The surrounding walls are indicated by the blue border. Beyond the walls is the wilderness, the dry and barren landscape of the Iranian Plateau. It was the king’s responsibility to ensure that the walls were kept intact, and that life inside the garden could flourish. This imagined place of perfection was called fraša in Old Persian, which is the origin of the Greek word ‘paradeisos’ (paradise).

Conserving a one-of-a-kind panel

In 2021, the museum started a project to conserve this important tile panel. After a century of being on display in the National Museum of Scotland's Grand Gallery, the old restoration work had begun to look tired.

A first visual inspection showed significant areas of repair and over-paint, so the entire panel was dismantled to understand better the extent of its historical restorations. The results surprised us.

The tiles that were thought to belong to one panel turned out to have been assembled from several ones with the same pattern. There were losses, variations in glazes and design elements that didn't match. These inconsistencies had been disguised by plaster fillings and over-painting to achieve a coherent appearance.

It was a difficult choice. Should the tiles be reassembled into one panel? And if yes, how could its complicated story be made visible?

In its historical formation, the panel had preserved culturally important information that was vital to maintain. The decision was therefore made to reassemble the tiles in their previous order, but also to make gaps obvious. Neutral background colours – white for the central field and dark blue for the border – were chosen to show where tiles or fragments are missing.

Acquiring the panel

The acquisition of the panel is recorded in the museum’s register as a gift by John Richard Preece (1843–1917). Preece was British Consul in Isfahan and an old acquaintance of Robert Murdoch Smith (1835–1900), Director of the Edinburgh Museum of Science and Art as the National Museum of Scotland was called back then. Both men had worked together in Iran.

It is likely that the acquisition of the tile panel was made possible due to their relationship. During his years in Iran, Preece had gathered a valuable collection of Iranian antiquities. He would have been aware of building activities in Isfahan, and the sources that local antiques dealers used to procure tiles. The Haft Dast palace was in use until the late 19th century. The German Ernst Hoeltzer (1835–1911) described it as a ‘summer palace of the Shah[,] partly old and new’, occupied by different governors for short periods and a refuge for disgraced high-ranking officials from Tehran ('Persien vor 113 Jahren', p. 105).

In the late 1890s, as part of the urban modernisation under the Qajar dynasty (1785–1925), the palace was finally demolished.

Acknowledgements

The Iranian tile panel was conserved with Art Fund support in 2021.

The conservation of the panel was a cross-disciplinary collaboration between Holly Daws, Charles Stable and Friederike Voigt.