Discover

Fascinating stories behind our collection, from the prehistoric to the present.

With over 12 million objects and specimens in our museums and stores, we have a lot of stories to tell. Uncover hidden histories, discover breakthrough research, and dip in to different perspectives with our collection of articles and films.

Featured stories

Fashion and folklore of the Arnish Moor man

On the Isle of Lewis in the 1700s, a young man was mortally injured. His clothed remains were recovered 300 years later.

What is the Peebles Hoard?

Explore the hoard of exciting and complex Bronze Age objects, many of them never found before in Scotland.

An unsolved mystery: the coffins found on Arthur's Seat

Satanic spell, superstitious charm or echo of Edinburgh’s grisly underworld history?

Who was Mary, Queen of Scots?

- Discover

The life, death, and legacy of Mary, Queen of Scots

Arguably the most famous and controversial figure in Scottish history, Mary Stewart has become something of an enigma. Intrigue and romance have often obscured the hard facts of her life and reign. - Discover

Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots is one of the most famous yet enigmatic figures in Scottish history. Our collection contains a rich selection of objects associated with Mary. Explore her dramatic story and separate out the facts from the myths that… - Discover

The controversial letters associated with the Mary, Queen of Scots Casket

The Mary, Queen of Scots Casket is one of Scotland’s most cherished treasures, thanks to its long-standing association with the controversial queen. - Discover

Mary, Queen of Scots and the silver casket

The Mary, Queen of Scots Casket is one of Scotland’s most cherished treasures, thanks to its long-standing association with the controversial queen. Take a closer look at this extremely rare work of early French silver and its associations… - Discover

A brief history of James VI and I

James VI and I was a hugely significant Stewart king. But he has been overshadowed by his notorious relations. His predecessor in Scotland was his mother, Mary, Queen of Scots. In England, his cousin, Elizabeth I, and finally his successor… - Discover

True or False: Objects associated with Mary, Queen of Scots

The life and death of Mary, Queen of Scots has given rise to countless legends over the years. Many places and objects acquire a new glamour through their association with her - genuine or otherwise. In our collection we have many items…

Exhibition deep dive: Cold War Scotland

How Scotland became a Cold War battleground

Drawing on never-before-seen archives, object collections, footage, and interviews with experts, this film explores Scotland's critical position on the frontline of the Cold War.

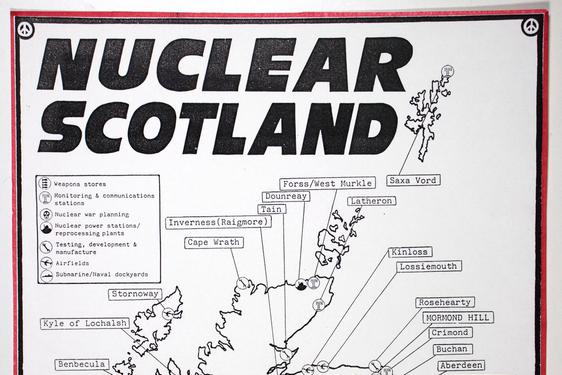

Nuclear Scotland during the Cold War

Discover the history and impact of nuclear power in Scotland during this period.

The Cold War and Scottish society

Scotland was the site for cultural and political exchange from both sides of the Cold War across the 20th century. This film delves into the stories of the Cold War and Scottish society.

Ever wonder how minerals are named?

Latest stories

- Discover

Reviving Mayan ceramics: the Smoking Monkey Vase

This lively ceramic vessel by Mayan artist Patricia Martín Morales shows a procession of animals and spiritual beings enjoying the intoxicating effects of cacao and tobacco. - Discover

A medieval masterpiece: The Monymusk reliquary

The Monymusk reliquary is arguably the most important piece of early Christian metalwork to survive in Scotland. - Discover

9 summer customs in rural Scotland

Explore stories of spring in rural Scotland through tools, machinery and photographs from the rural history collections. - Discover

A unique 3000-year-old hat made of horse hair

In 1953, when Donald John Mackay was out peat-cutting near Kirtomy in the old county of Sutherland with his 10-year-old daughter Babette, his spade brought up a curious mass of hair, bound into coils. Little did he know that he had just… - Discover

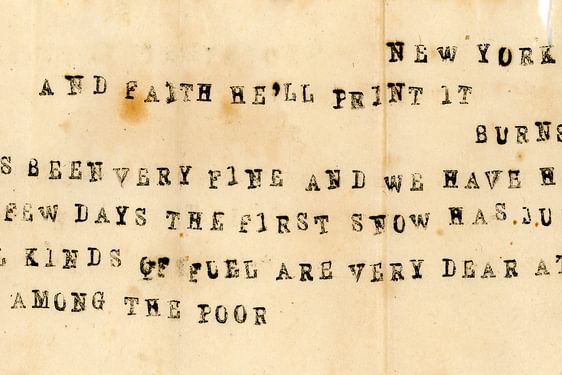

Type-writing ahead of time: John Galloway’s inventions

In the early 1800s, Paisley-born John Galloway immigrated to America. Through his letter home in 1868, we can see the progress of his type-writing inventions, years before the typewriter as we know it. - Discover

Women of Cold War Scotland

Scotland played a unique role during the Cold War, a 40-year nuclear stand-off between the USA and the Soviet Union. Despite looming conflict, people in Scotland mobilised in a variety of ways in reaction to this changing world. Thousands…

Header image: The runic inscription on an arm band found in the lower deposit of the Galloway Hoard. Museum reference X.2018.12.54. Read A runic revelation: who owned the Galloway Hoard to learn more about the Galloway Hoard, and the research behind this inscription.