Key in a search term below to search our website.

Key in a search term below to search our website.

Robert I, also known as Robert the Bruce, was king of Scots from 1306 to 1329. Bruce is often portrayed as a national hero, the defender of the Scottish kingdom against the English during the turbulent Wars of Independence. His gifted leadership and sense of military strategy are clear, but the reality is more complex than this.

Robert I was the first in a new royal line and had gained the throne by controversial and violent means. He needed to quickly and effectively establish his legitimacy as king and Scotland’s independent authority as a kingdom. As well as a significant programme of written propaganda, some of the ways he achieved this can be seen in surviving objects from the period. His descendants built on this foundation, adding to the myth and gaining from their dynastic connection. Over the centuries, many stories and objects were drawn into the Bruce legend – testament to the continuing relevance and reimagining of this king of Scots.

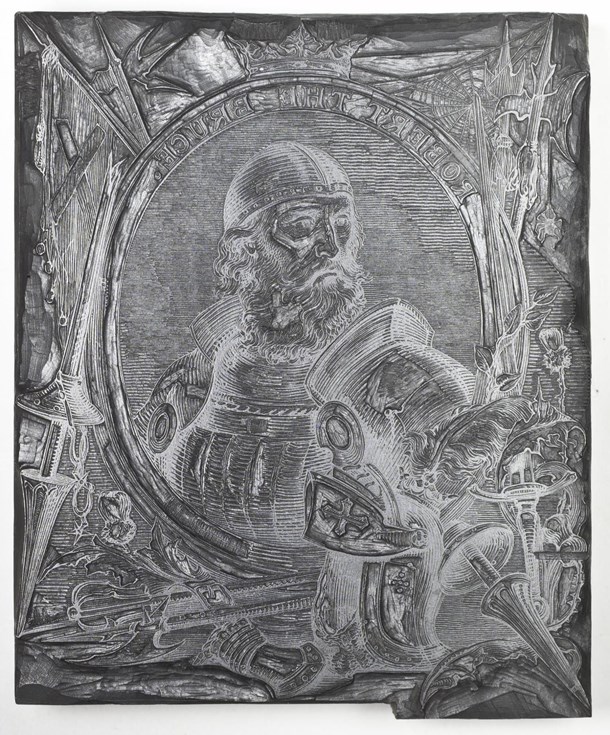

Woodblock depicting Robert the Bruce, wood, one of a collection of woodblocks of illustrations used by W. & R. Chambers Ltd, 1840s - early 20th century

On a stormy night in 1286 Alexander III, king of Scotland, set out from Edinburgh to visit his new wife. He never arrived, and after the death of his appointed heir – seven-year-old Margaret Maid of Norway – in 1290, Scotland was left without a clear heir to the throne. Thirteen rival claimants sought the Crown in what became known as the Great Cause. From among them, two main competitors emerged: Robert Bruce’s grandfather, the fifth lord of Annandale, and John Balliol, lord of Galloway.

Above: Brown sulphur cast of the reverse of the 1st Great Seal of John I (Balliol).

Above: Brown sulphur cast of the observe of the 1st Great Seal of John I (Balliol), depicting the king on his throne.

In 1292, the Bruce claim was formally rejected in favour of John Balliol, who was duly crowned king of Scots. But Balliol’s reign was short-lived – in 1295 Scottish magnates transferred his power to a council of twelve guardians made up of earls, barons and bishops. Bruce refused to swear fealty to Balliol, and when Edward I invaded Scotland in 1296, Bruce joined the English forces against his king.

Balliol was forced to abdicate within a few months of this defeat. Bruce resumed his family’s claim to the throne, though he still faced opposition – Balliol had been crowned and many Scots held out for the king’s return from exile. In February 1306, Bruce lost his patience. At the altar of Greyfriars church in Dumfries Bruce killed John Comyn, a staunch supporter of the Balliol dynasty and head of the most powerful baronial families in Scotland. Six weeks later Bruce was crowned King Robert I at Scone, Perthshire. At the time, Bruce’s actions were controversial and many saw him as a violent usurper.

Following the murder of Comyn, Bruce needed to assert his authority and establish himself – not the Balliol dynasty – as the rightful head of the kingdom. The essential tool for medieval authority and governance was the seal. Wax seals bore symbols and words that proclaimed the authenticity of a document and the power of their owner.

Robert’s great seal deliberately drew connections with the past to underline his legitimacy: like monarchs before him, Robert I is shown mounted on a horse and bearing arms. Unlike previous kings, Robert is turned to face the viewer in a combative, aggressive posture that has been read as a challenge to England’s Edward I. During the English administration of Scotland, Edward I’s seal for Scotland had depicted him enthroned, emphasising his removal of the tangible symbols of Scottish royal power – including the Stone of Scone – to England. The great seal of Robert I emphasises his military might in the face of English claims over the Scottish kingdom.

Above: Cast of the Great Seal of Robert I.

Above: The Bute mazer, on loan from the Bute Collection at Mount Stuart.

The cup known as the Bute mazer (or the Bannatyne mazer) is one of the best surviving evocations of the richness of medieval visual symbolism. This fascinating object, on loan to National Museums Scotland from The Bute Collection at Mount Stuart, also shows how this symbolism could be reworked and redeployed hundreds of years later.

The mazer is a large drinking cup. The lid, the bowl and most of the silver fittings were made in the early 16th century, probably for Ninian Bannatyne of Kames, who is named on the inscription that runs around the rim. The mount inside the bowl is two hundred years older, and was made during the lifetime of Robert I.

Above: The 14th-century mount inside the Bute mazer, on loan from the Bute Collection at Mount Stuart.

This 14th-century mount is dominated by a substantial lion, thought to symbolise Robert I. Ranged around it are enamelled shields bearing the heraldic arms of powerful figures from south-west Scotland – supporters of Robert from the region of his own lordship. The arms include those of Bruce’s close ally Sir James Douglas. After Bruce’s death in 1329, Douglas pledged to take Robert I’s heart on pilgrimage to the Holy Land. In recognition of this deed, the Douglas arms after 1329 gained a heart and its absence here confirms the mount was made during Bruce’s lifetime.

Above: A 14th- or 15th-century wooden platter from Threave Castle, Dumfries and Galloway, bearing the heart of the Douglas family arms.

The Stewart arms are placed between the lion’s paws in testament to the status and wealth of Bruce’s son-in-law but also perhaps a hint that this family had commissioned the making of this sumptuous and highly symbolic object. This mount, perhaps originally the lid for another cup, was a powerful and symbolic statement by the supporters of Robert I.

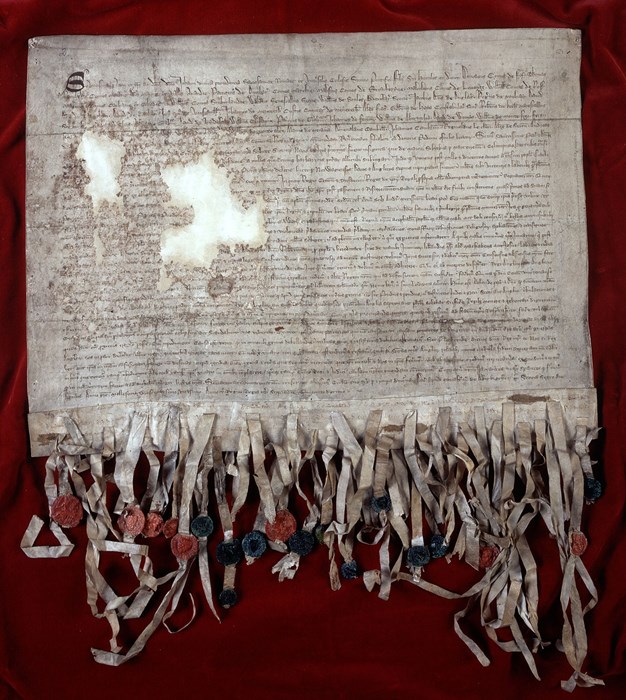

In later years, Bruce’s chancery sought to justify his violent actions in 1306, and written sources from the period have left an enduring legacy. Most familiar today is a letter to the Pope written in 1320, known since the 20th century as the Declaration of Arbroath.

Robert I’s victory over the English at the battle of Bannockburn in 1314 had not brought the expected rewards and recognition: Bruce still had opponents in Scotland, and neither the Pope nor England’s Edward II recognised him as king. The Pope called for a truce to enable both kingdoms to devote more money and energy to a crusade in the Holy Land. The fear in Scotland was that the Pope would acknowledge England’s sovereignty over the Scottish kingdom as the basis for this peace settlement.

Bruce summoned a council to Newbattle Abbey to discuss a response: three letters were written and sent to the Pope in Avignon – one from the king, one from the church and one from the barons of the realm. The barons’ letter was written up at Arbroath Abbey, and the surviving document is a copy that was kept in Scotland for the chancery’s records (the original having been dispatched to the Pope).

Above: The Declaration of Arbroath. © National Records of Scotland.

The letter sought to justify continuation of the war with England by setting out the legal and philosophical case for Scottish independence. It opens with a retelling of Scotland’s ancient past, framed to show the kingdom’s long pedigree as a free and autonomous entity. The Declaration was not the first letter proclaiming Scotland’s independence, nor the first attempt by Bruce to garner the acceptance as king of Scotland at home and abroad, but it was the most eloquent, concise and effective articulation of this argument that had yet been produced.

Through carefully constructed arguments, deliberately framed to appeal to legal and theological sentiments popular at the papal court, the letter sought to demonstrate that it was not Robert I’s stubbornness that prevented a truce: the letter states that should the king submit to England, the barons of Scotland would replace him with another. Kings of England and France had previously adopted similar tactics to deflect papal pressure, producing letters evoking the communal opinion of the elite nobility to back up their cause.

The seals of nineteen Scottish magnates survive attached to the document, of the fifty or so that were originally affixed. The names of those who put their names to the letter suggests it was produced as a matter of urgency – magnates based in the south-east of Scotland or within easy reach of Newbattle are overrepresented. Though many powerful figures are named in the 1320 letter, an attempted coup shortly after it was written underlines that support for Robert I was not as strong as the document suggests.

Though peace between the kingdoms was some time in coming, papal replies sent to Scotland in summer 1320 show that one of Robert’s aims had been achieved – they addressed him as ‘illustrious king of Scotland’.

““Our most valiant prince and lord, the lord Robert, who, that his people and his heritage might be delivered out of the hands of the enemies, bore cheerfully toil and fatigue, hunger and danger, like another Maccabeus or Joshua”- Declaration of Arbroath, 1320

Robert I died at the age of 55 on June 7th 1329 at his house in Cardross. Robert had been seriously ill for several years – some medieval accounts suggested he had contracted leprosy although the cause of his death is uncertain.

On his deathbed, Robert had asked that his heart be removed and taken to the Holy Land by Sir James Douglas. After the failure of this task, the heart was returned to Scotland and buried at Melrose Abbey. In 1996, excavations at the abbey found a lead container, housing a further small container and a plaque recording that it had been discovered in 1921 to contain a heart. The casket was reburied in 1998.

Above: The casket at Melrose Abbey believed to hold the heart of Robert the Bruce. The inscription reads ‘A noble hart may have nane ease gif freedom failye’. Photo by Jelle Druyt CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

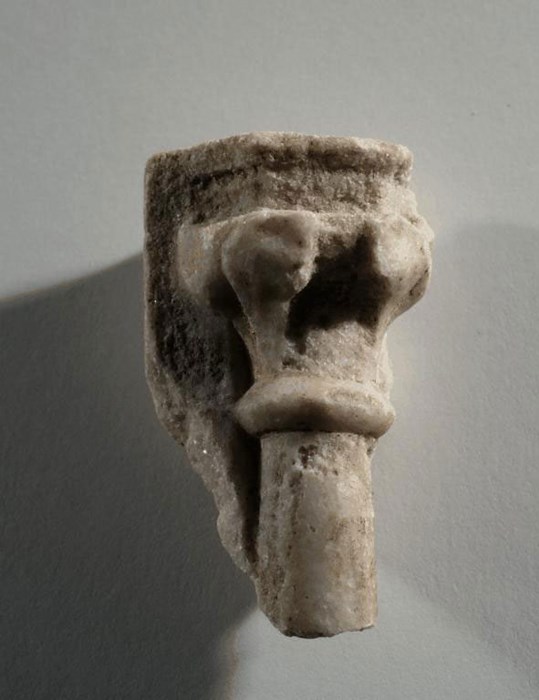

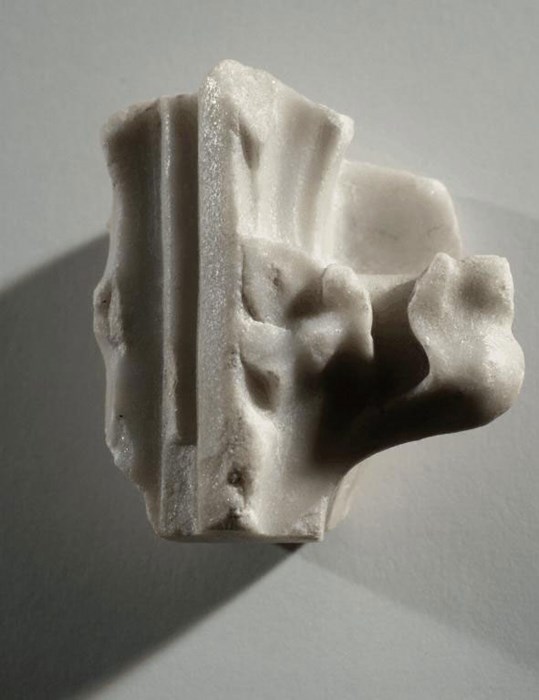

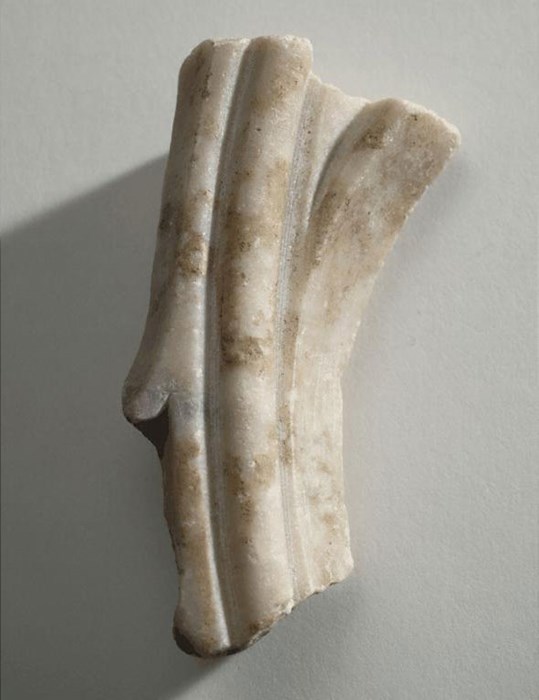

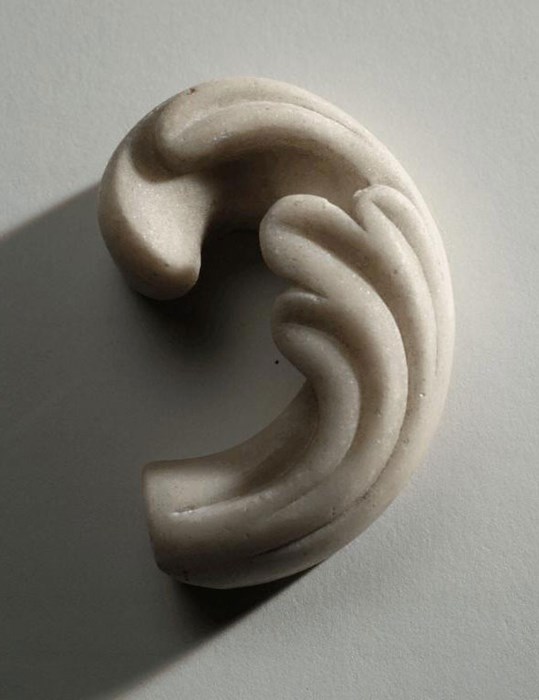

The rest of Robert’s body had been buried within Dunfermline Abbey, the resting place of Scottish rulers since the early 12th century. An elaborate gilded marble tomb carved in France marked his resting place in the abbey’s choir. This tomb was destroyed during the Reformation, though fragments of alabaster found at Dunfermline may have once belonged to it.

Above: Fragments from the tomb of Robert the Bruce.

The film below shows a 3D reconstruction of the tomb.

Above: The Lost Tomb of Robert the Bruce. This project was a collaboration between The Royal Commission for Ancient and Historic Monuments of Scotland (RCAHMS), Historic Scotland, The Hunterian (University of Glasgow), National Museums Scotland, Fife Cultural Trust, the Abbotsford Trust, the National Records of Scotland, the Digital Design Studio (Glasgow School of Art) and received research grant funding from the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. The visualisation below is © Centre for Digital Documentation and Visualisation LLP (a partnership between the School of Simulation and Visualisation at the Glasgow School of Art and Historic Environment Scotland).

During alterations to the church in 1818 a burial was unearthed – the skeleton was encased in lead and buried in a decayed wooden coffin with remains of gold cloth. The skeleton bore indications that the chest had been opened to remove the heart, suggesting it may indeed have been the remains of Robert I. After a cast of the skull was made, the remains were reburied in the church.

Above: Fragments of gold cloth, possibly from the tomb of Robert I. NMS: H.KJ 149

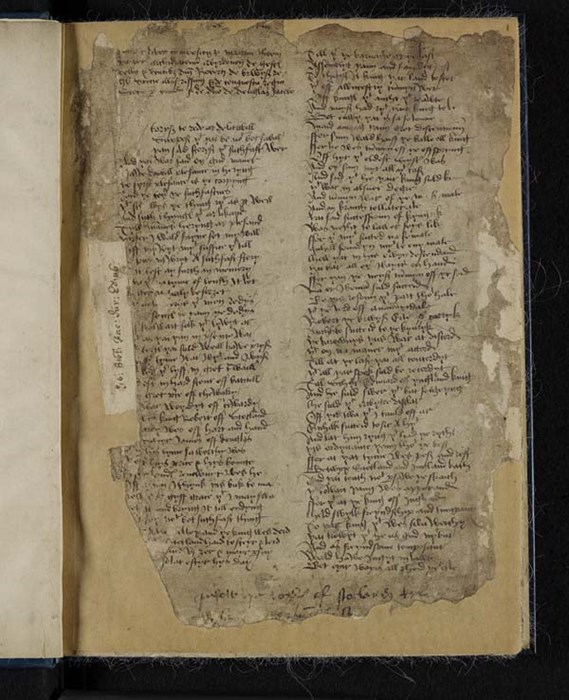

Bruce’s descendants built on Robert I’s reputation, gaining from their association with his heroic exploits. Robert’s grandson Robert II commissioned an epic narrative poem ‘The Brus’, written by John Barbour. The poem centres around an extensive account of Bannockburn, and casts Bruce as a chivalric hero. This masterpiece of propaganda has coloured perceptions of Robert I ever since it was written.

Above: Page from a 1489 copy of 'The Brus' by John Barbour, held in the collection of the National Library of Scotland. Image CC BY 4.0.

In the centuries that followed the death of Bruce, objects and stories were attracted to his legend. The Brooch of Lorn, on loan to National Museums Scotland from the MacDougall of Dunollie Preservation Trust, was said to have been taken from Bruce in 1306 as he fled retribution for the murder of Comyn. Though the brooch has assumed an important place in the legends associated with the MacDougall clan, its style suggests it was made at least a hundred years after Bruce died. It is possible that, like the Bute mazer, a 14th-century brooch was refashioned in subsequent centuries. But the desire to link 15th or 16th-century objects like the Brooch with stories about the 14th-century Robert I shows the strength and development of Bruce’s legend as a heroic and patriotic king well beyond his own times.

Above: The Brooch of Lorn, on loan from the MacDougall of Dunollie Preservation Trust.

Objects much older than Bruce have also been drawn into his story. When the 8th-century Monymusk reliquary was discovered in the 19th century, a legend quickly grew up around it that linked it to Robert Bruce. Medieval written sources referred to a battle standard that had been carried by Bruce’s forces at the Battle of Bannockburn and was associated with St Columba. In the 19th century, scholars suggested that this battle standard was not a flag or banner but the early medieval Monymusk reliquary. Only recently have historians revisited this story and found no evidence to connect Robert Bruce or Bannockburn to the early medieval reliquary, an object that would have been 500 years old in 1314.

Yet with Bruce's story regularly revived in film and literature, the fascination with this complex king is still strong in the 21st century.