Key in a search term below to search our website.

Key in a search term below to search our website.

““Whence the broach of burning gold, That clasps the Chieftain's mantle fold, Wrought and chased with rare device, Studded fair with gems of price.”

The Brooch of Lorn, top view (diameter: 90mm) © National Museums Scotland, courtesy of MacDougall of Dunollie Preservation Trust (IL.2012.62).

Having not seen the brooch in person, we can forgive Scott for thinking that it was made of ‘burning gold’. The Brooch of Lorn is crafted from silver but Scott was right to imagine that it was heavily decorated. Almost every surface is ornamented in some way. In the middle, a large scalloped ‘tower’ holds a prominent rock crystal in a silver setting. Around it, eight turrets rise up from the base plate, each grasping a pearl. Originally owned by the MacDougalls of Lorn, the brooch is large and imposing - a real status item.

The Brooch of Lorn, side view (height: 58mm) © National Museums Scotland, courtesy of MacDougall of Dunollie Preservation Trust (IL.2012.62).

Take a closer look at the detail of the Brooch of Lorn in this 3D spin.

Hammer marks are visible on the reverse of the brooch from the hands that worked it. The pin is similar in form to those seen on brooches of the late 16th and early 17th centuries. However, traces of solder elsewhere on the back of the brooch suggest the brooch might have originally had a different pin.

The Brooch of Lorn, reverse © National Museums Scotland, courtesy of MacDougall of Dunollie Preservation Trust (IL.2012.62).

The brooch has no maker or date marks, but there are stylistic clues that can tell us about where and when it might have been made. It is one of three ‘turreted’ brooches, all with similar striking features. The closest parallel is the Lochbuy (Lochbuie) Brooch in the collection of the British Museum; a facsimile is on display at the National Museum of Scotland.

Facsimile of the Lochbury Brooch, on display at the National Museum of Scotland (H.NGD 12).

Although larger than the Brooch of Lorn, with ten turrets rather than eight, the design is so similar that the two brooches may have been made by the same hand or workshop. The Lochbuy Brooch bears a later, probably 18th century, inscription on the reverse, claiming that it was made on the estate of Lochbuy (Isle of Mull) about the year 1500 and has links to the Campbells and Macleans.

Facsimile of the Lochbury brooch, reverse.

A third brooch with stylistic similarities to the brooches of Lorn and Lochbuie is known as the Ugadale Brooch, which was originally owned by the Mackays of Ugadale (Kintyre). Like the other two brooches, it features a large central stone, in this case framed by eight turrets topped by coral beads as well as pearls.

Electrotype facsimile of the Ugadale, or Lossit, brooch, on display at the National Museum of Scotland (H.NGD 11).

All three brooches have a strong clan connection in the Argyll region and were clearly made as status items. Stylistic features of the turreted brooches suggest they date to around 1600, though they may draw on a slightly earlier tradition of smaller gem-set ring brooches.

Tradition tells of a much earlier history for the Brooch of Lorn, centred on an association with King Robert I of Scotland, popularly known as Robert the Bruce (reigned 1306–1329).

Thomas Pennant wrote about a ‘curious brotche [brooch]’ in his 1772 A Tour in Scotland, and Voyage to the Hebrides:

“On this spot [the plain of Dalrie] was the conflict between Robert Bruce, and the forces of Argyleshire, under Mac-dougal chieftain of Lorn, when the former was defeated. A servant of Lorn had seized on Bruce, but the prince escaped by killing the fellow with a blow of his battle-ax; but at the same time lost his mantle and brotche, which the assailant tore away in his dying agonies.”

Sir Walter Scott repeats this narrative in his poem The Lord of the Isles (1815):

Moulded thou for monarch's use,

By the over-weening Bruce,

When the royal robe he tied

O'er a heart of wrath, and pride;

Thence in triumph wert thou torn,

By the victor hand of Lorn!

Pennant and Scott were writing in the 18th and 19th centuries, long after the events they describe, and earlier accounts of the Battle of Dalrigh make no mention of a brooch being snatched from the breast of Bruce. In its current form, the brooch is two or three centuries later in date than Bruce, though it is possible, perhaps even likely, that the rock crystal had an older history. The Ugadale Brooch has also been linked in oral tradition to Robert the Bruce.

The stones on the Brooch of Lorn are not there by chance, chosen for what were believed to be their protective, curative or transformative powers. Since pre-history, rock crystal and quartz have long been sought for these beneficial properties. They were often bound or mounted in silver and used as charms to protect against sickness or the effects of magic, often in animals. This typically involved dipping them into water whilst saying a charm or prayer. The pearls on the Brooch of Lorn, coming from a watery context, might have enhanced the significance of the rock crystal. A fragment of red textile, probably silk, under the rock crystal gives the stone a red-pink lustre in certain light.

The Ballochyle Brooch, silver gilt and set with a central crystal. Previously owned by the MacIver Campbells of Ballochyle (H.NGB 177).

These large rock crystals were often said to be connected with high-profile people or historic events such as the Crusades. Whether these associations are accurate or not, their perceived status as ‘relics’ of the past enhanced their significance and probably explains their inclusion in status jewellery like the Brooch of Lorn.

A crystal charmstone, previously owned by the Campbells of Glenorchy and said to have been worn by Sir Colin Campbell when fighting the Turks in Rhodes in the 15th century (H.NO 118).

Together, the combination of the rock crystals’ potential history, the talismanic attributes of the stones, and the intricate ornamentation of their setting make such brooches very powerful objects.

Rock crystal charmstone of the Stewarts of Ardsheal, with a silver frame and chain for dipping in water (H.NO 72).

The Brooch of Lorn is often described as a ‘reliquary brooch’. Reliquaries are objects used to house special relics, usually in a Christian context, although here the term appears to be used more broadly to describe an object with a hidden chamber.

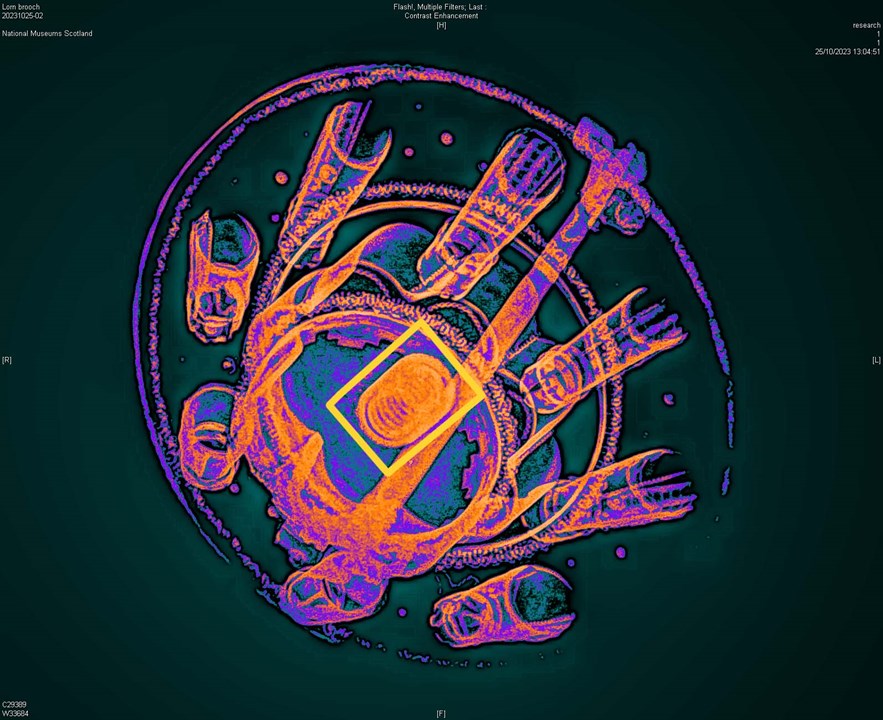

X-ray image of the Brooch of Lorn, showing a central screw within the central eight-lobed tower and situated beneath the rock crystal. © National Museums Scotland, courtesy of MacDougall of Dunollie Preservation Trust.

In October 2023, with the kind permission of the MacDougall of Dunollie Preservation Trust, the brooch was assessed using X-radiography (X-ray). Excitingly the results showed a hollow central chamber with what appears to be a screw mechanism beneath the crystal, suggesting the brooch opens. It is possible that the central chamber originally housed a written charm, worn close to the body and intended to work in partnership with the precious stones on the outside of the brooch, or a relic of a particular individual.

X-ray image of the Brooch of Lorn with colours inverted to better detail the screw mechanism (highlighted yellow) inside the central tower © National Museums Scotland, courtesy of MacDougall of Dunollie Preservation Trust.

View the Brooch of Lorn from all sides in this 3D image.

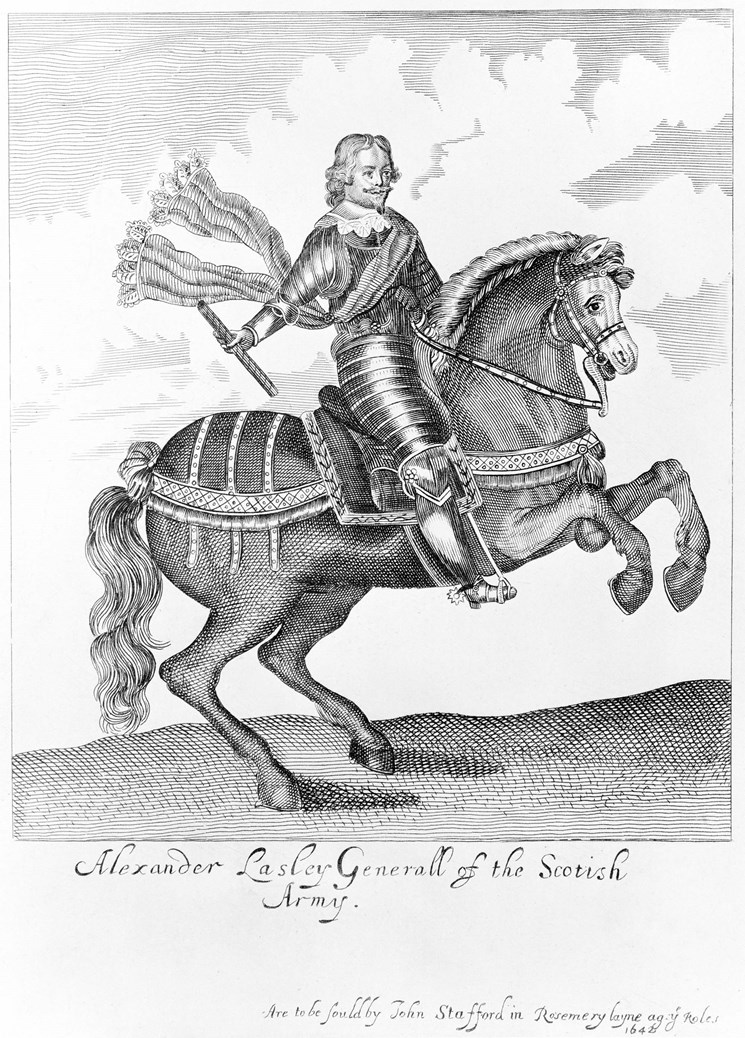

The Brooch of Lorn can claim a dramatic history. Both Pennant and Scott believed that the brooch had been lost in a fire at one of the MacDougall residences. In 1647, during the period of civil strife known as the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, Gylen Castle – a MacDougall stronghold on Kerrera – was sacked and burned by Covenanting forces fighting on the side of parliament, under the command of General Leslie.

An engraving of General Alexander Leslie, c. 1642 (M.1955.484).

It is said the brooch was seized by Campbell of Inverawe at this time and passed down through the family, all the while believed lost by the MacDougalls. It resurfaced at a public sale just a few years after Scott published The Lord of the Isles, and was eventually gifted back to Clan MacDougall by General Campbell of Lochnell in 1824, more than 170 years after it had been taken.

The Brooch of Lorn has since been cared for by the MacDougalls of Dunollie and admired by many over the years, including Queen Victoria in 1842. Since 2012 it has kindly been on loan to National Museums Scotland from the MacDougall of Dunollie Preservation Trust and is on display in the Kingdom of the Scots gallery.