Key in a search term below to search our website.

Key in a search term below to search our website.

The unicorn is first mentioned in a long lost book about India about 400 BC and eventually is adopted as Scotland's national animal in the 15th century and can now be seen everywhere.

Unicorns did once roam the earth

Elasmotherium Sibericum, a distant relative of the modern rhinoceros, disappeared less than 40,000 years ago.

A strange creature indeed

In 1901, Sir Harry Johnston went to Congo looking for a unicorn and instead found the Okapi.

Prickly French emblem

In the 15th century, most of the European nobility adopted animal emblems such as the unicorn, and for the French king it was the porcupine.

Lots of unicorns in Scotland

You will find lots of unicorns in Scotland on historical buildings, on gold coins and on the top of some Mercat crosses.

Left or right?

In Scotland, the Unicorn stands on the left of the Royal coat of arms, whilst in England, this is where the Lion is found.

Although the origins of the unicorns are subject to debate, the first known mention of a quadruped with cloven hooves and a single horn sprouting from the middle of its forehead could be found in a long-lost book about India, Indika, written in Greek by Ctesias. Ctesias was physician to Artaxerxes II Mnemon, King of Kings of Persia from 404 to his death in 358 BC.

Hearsay would become a common theme in the legend of the Unicorn. Ctesias never set foot in India, nor saw a unicorn, but he’d been shown a horn, a hoof and a gall bladder by merchants, on the testimony of which he made his description.

From then on, the characteristics of the unicorn were fixed. It had a single horn (although, in Ctesias’ description, it is white, red and black) and it was extremely fast, making it near-impossible to capture, and became known on a global scale. Belief in the unicorn spread with cultural exchanges between civilisations, often with Persia at its centre.

For Europeans, the existence of the unicorn was backed up by mentions in the Bible. Somewhere between the middle of the 3rd and the middle of the 2nd century BC, the Old Testament had been translated in Greek.

Amongst the words upon which the translators stumbled was רְאֵם , re’em, a word we now know designates aurochs, an animal which had disappeared from the Greek-speaking world before the 5th century BC. At loss for a name, they chose μονοκέρως (Monoceros), the Greek for Unicorn. And voilà, the unicorn was now a biblical creature.

A few centuries later (somewhere between the 2nd and 4th century AD), another Greek author, known only by the name they gave to their book, Physiologus, a compendium on animals and their Christian symbolism, added a new layer to the myth of the unicorn: they related the single horn of the animal to the mystery of the Trinity. As such, only a virgin could capture it (in the 12th century, Hildegard von Bingen added a precision: it had to be a young virgin, still in her teens, not an old maid).

Later on, in the 10th century, Persian medical texts start to relate that both the Chinese and the Egyptian Fatimids were using a material called khūtū to make (mostly) knives, as it is able to detect (and cure) poison. Although descriptions of khūtū vary, it was, mostly, of two sorts, one shorter and curved, the other longer and spiralled one: walrus and narwhal tusks, harvested by the Norse in Greenland and traded to Persia by the Bulgars.

Above: Male narwhal cast at the National Museum of Scotland.

The belief that the unicorn was such a pure animal and that its horn protects from poison spread throughout Europe, Northern Africa and China, through the boost in the Greenlandic trade, thanks to the good climatic conditions of the 12th and 13th century.

In the 15th century, most of the European nobility are adopting animal emblems, often wild and uncommon ones (the lion for the kings of England, the porcupine for the kings of France, the eagle in Spain, etc.). In Scotland, James I went for the unicorn. We don’t really know why.

Some have said because the unicorn was the mortal enemy of the lion, but this idea doesn’t really develop until the 17th century when the Lion and the Unicorn had to live together after the union of the crowns. It could have been because, in medieval novels, Bucephalus, the horse of Alexander the Great, was often depicted as a unicorn. Some other medieval legends said only kings could hold a unicorn captive, and the choice of the animal could have been urged by the memory of James I’s captivity. More research needs to be done to find the reason behind the Scottish unicorn.

Whatever the reason for its adoption, the unicorn then starts to become a frequent sight in Scotland. It bore the arms of Scotland on the seals, and James III chose it as the emblem adorning the gold coins he, his son James IV and his grandson James V issued. More widely, it could be seen on monuments, like the panels from the Franciscan Nunnery Chapel in the Overgate, Dundee. Today, one can still find them on top of Mercat crosses in Edinburgh or Prestonpans, on the façade of Craigmillar castle and in many other places.

Kim Traynor [CC BY-SA 3.0] from Wikimedia Commons

After the union of the crowns under James VI, the unicorn started to share its space with the Lion, giving their name to many a public-house, and also serving as substitutes in art and literature to describe the troubled union between England and Scotland. In fact, in Lewis Carroll’s fantasy story, Through the Looking Glass, the White King is quoted as saying “They’re at it again”.

Royal coat of arms of the United Kingdom. By Sodacan - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, Link

Scottish version of the Royal coat of arms. By Sodacan - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, Link

If you observe carefully, you’ll notice that, in Scotland, the Unicorn stands on the left of the royal coat of arms, whilst in England, this is where the Lion is found: each animal is at the place of honour when in his own country.

For centuries, people have tried to find unicorns, but they remained elusive. All the stories about finding unicorns do have one thing in common: no matter how far the adventurer goes, they live three days march away.

Except for two of them: Marco Polo, traveller extraordinaire, who, after seeing rhinos in India, went to Sumatra, where he actually saw unicorns, of which he gives a very precise description, not hiding his disappointment (“it’s a very ugly beast”). In fact, what he saw were Javan Rhinoceroses, a species that has since then been hunted to near extinction.

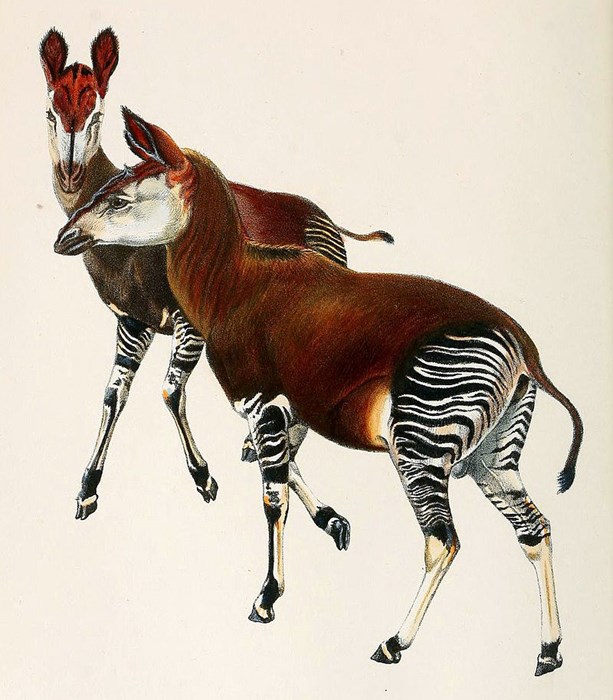

Above: Okapi painting by Sir Harry Johnston (1858-1927), lithograph by P. J. Smit, via Wikimedia Commons.

Centuries later, in 1900, the British governor of Uganda, Sir Harry Johnston, rescued some pygmies from Congo abducted by a German merchant. He took advantage of his trip to bring them back home to assert the truth of Henry Morton’s Stanley accounts of the Atti, an ass assimilated to an African Unicorn. Although what he found was not a unicorn, he “discovered” (from a European point of view, that is), another strange animal, the Okapi.

More surprisingly is the fact that unicorns did actually roam the earth not that long ago. A recent study led by Professor Adrian Lister, Merit Researcher at the Natural History Museum, has shown that Elasmotherium Sibericum was a distant relative of the modern rhinoceros. It had a horn which sprouted from the middle of its forehead and had survived far longer than initially thought, disappearing only 40,000 years ago.