Key in a search term below to search our website.

Key in a search term below to search our website.

© Mike Brooks © King’s Printer for Scotland, National Records of Scotland

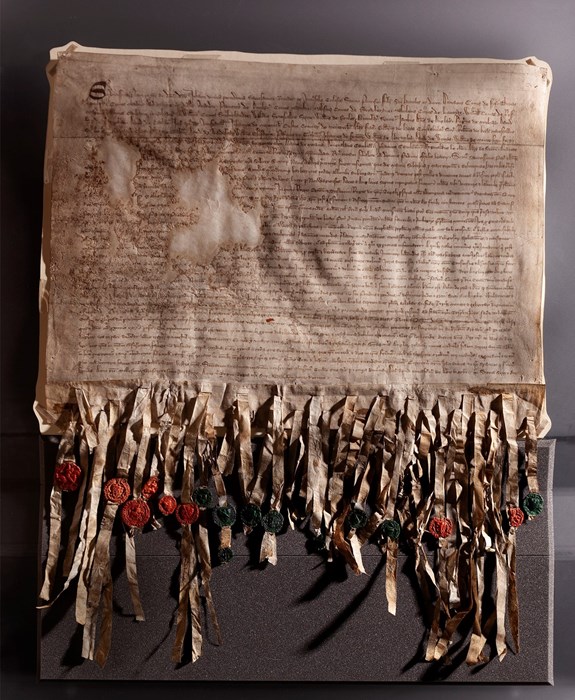

The Declaration of Arbroath prepared to go on display at the National Museum of Scotland from 3 June to 2 July 2023. Image: Mike Brooks © King’s Printer for Scotland, National Records of Scotland

While the Declaration of Arbroath was sent in the name of important Scottish noblemen, it was a government initiative of King Robert I, who is often referred to as Robert the Bruce. The 1320 letters were written because Robert was facing mounting international pressure and because of growing domestic concerns in Scotland.

In April 1318 Robert had recaptured the town of Berwick, a prosperous trading centre which was once part of Scotland and is now known as Berwick-upon-Tweed. This action broke a papal truce and triggered a barrage of papal communications to Scotland. Bruce had already been excommunicated for the murder of his rival, John Comyn, in Greyfriars Church in Dumfries in 1306, but the excommunication was reaffirmed after 1318. Worse still, the Pope released Robert’s subjects from loyalty to him. Robert had, in effect, the full weight of international papal sanctions thrown at him, a situation he urgently needed to address.

A nineteenth-century imagining of the murder of John Comyn at Greyfriars Church, featuring very anachronistic clothing and weapons, by Henri Félix Emmanuel Philippoteaux c.1856-7. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Robert also faced growing domestic problems. In October 1318, Robert’s last remaining adult heir, his brother Edward, was killed in battle in Ireland. In December 1318 a parliament at Scone was called to sort out his succession, naming Robert's infant grandson, Robert Stewart, as his heir. However, a credible rival king was available in Edward Balliol, son and heir of the inaugurated King John Balliol (r.1292 – 1296).

There are also indications of growing opposition amongst some of Scotland’s barons. Many of those named in the Declaration of Arbroath were Robert’s supporters, but four of the individuals were implicated in a conspiracy against Robert a few months after it was dispatched. It seems likely that Declaration of Arbroath also represented a test of loyalty for some.

Many people feel a connection to the Declaration of Arbroath because they share a family name or connection with those individuals named in the document. As was the norm for medieval documents, the Declaration was not signed. Instead, wax seals were attached to show that the individuals in whose name the letter was sent authorised its contents. The seals are attached to the bottom of the document by parchment tags. Red wax was used for the most important earls, and green for lesser earls and barons. Nineteen seals survive today, though as many as 50 may originally have been attached.

Not signed, but sealed. Wax seals affixed to the Declaration of Arbroath confirm that those named in the Declaration's preamble authorised its message. Image: Mike Brooks © King’s Printer for Scotland, National Records of Scotland

The letter opens with a list of 8 earls and 31 Scottish barons in whose name it was sent. Not all of these people attached their seals to the document, and some of the seals that survive belonged to people who do not appear in the list. This mismatch might be down to practical factors and the haste in which the letters were drawn up. The letters were planned in March, and the fair copy dated only a month later.

People needed to be contacted, support garnered and their seals gathered together. Some were too far away, or could not supply a seal in time. Some of those named may not have seen the document themselves, but would have sent a clerk with a seal matrix to add the seal on their behalf.

The seal of Malcolm, Earl of Lennox, affixed to the Declaration of Arbroath. The writing reads, "[S’] MALCOLMI COMITIS DE L[EVENAX]". S' is short for 'sigillum' (seal). COMITIS means 'earl'. L[EVENAX] is 'Lennox'. Mike Brooks © King’s Printer for Scotland, National Records of Scotland, SP13-7

The content of the letter was probably drafted in March 1320 at a King’s Council at Newbattle Abbey, about 7 miles south-east of Edinburgh. The fair copy was later drawn up at Arbroath Abbey in Angus, at that time the location of the King’s writing office. Like other documents of the time, the letter carries a place-date: Arbroath 6 April 1320.

Ruins of Arbroath Abbey, cared for by Historic Environment Scotland. Image © David C. Weinczok

It is not clear exactly who authored the text. The Abbot Bernard has long been a strong candidate: at the time, Bernard was the royal chancellor and Abbot of Arbroath. Other candidates include Alexander Kinninmonth who was one of the emissaries who carried the letters to the Pope in Avignon. Both of these figures would have known the contents of the letter intimately.

A booklet produced by National Records of Scotland available in English and Gaelic includes a full translation of the text, including the names of those in whose name the letter was sent.

The Declaration of Arbroath. Image: Mike Brooks © King's Printer for Scotland, National Records of Scotland.

Use the controls within the image above to zoom or view it in full screen. Press "Escape" to exit full screen mode.

The text of the Declaration is around 1,000 words and written in a special kind of Latin prose style popular at the medieval Papal court. The letter opens simply with a list of the earls and barons in whose name it is sent. Following that it lays out the pedigree of the kingdom of Scotland, effectively making the case that Scotland was and had always been an independent entity. This passage is not grounded in historical reality but is a fascinating window on the medieval understanding of their ancient history. It has the Scots journeying from ‘Greater Scythia by way of the Tyrrhenian Sea and the Pillars of Hercules’ and dwelling for a long time in Spain, before travelling west to Scotland.

The letter then seeks to get the Pope on side by setting out Scotland’s close relationship with the Church through the claim that Scotland had been made Christian by St Andrew himself. Next, the Scot’s grievances against English king Edward I are laid out in vivid language, including ‘deeds of cruelty, massacre, violence, pillage and arson…’.

Following this, the letter sets out Robert Bruce’s case as Scotland’s legitimate king based on ‘divine providence’, on ‘succession to his right according to our laws and customs’ and on ‘the due consent and assent of us all’, that is the community of the realm. There is an assertion of loyalty ‘we are bound both by his right and by his merits that our freedom may be still maintained, and by him, come what may, we mean to stand’. That is followed by a famous passage asserting that, should Robert yield, should he seek to make Scotland subject to England, the community of the realm should drive him out and replace him with another.

“Yet if he should give up what he has begun, seeking to make us or our kingdom subject to the King of England or the English, we should exert ourselves at once to drive him out as our enemy and a subverter of his own right and ours, and make some other man who was well able to defend us our King . . .- The Declaration of Arbroath

These passages also include the well-known phrase: ‘It is in truth not for glory, nor riches, nor honours that we are fighting, but for freedom alone, which no honest man gives up but with life itself’. Interestingly this famous passage quotes a Roman text that was itself almost 1400 years old in 1320, by the politician and historian Sallust who was born around 86 BC. Its inclusion was presumably intended to trigger associations with that much older text and demonstrate the knowledgeability and sound underpinnings of the case set out by the letter.

A woodcut by Edmund Leighton (1852 - 1922) imagining King Robert I readying his soldiers before the Battle of Bannockburn, fought over two days on 23 and 24 June 1314. While the Scottish victory at Bannockburn did not end the war between Scotland and England, it did grant leverage and caused many within Scotland to more firmly support Robert I. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

The letter shows Scotland’s understanding of the Pope’s own priorities, pledging that Scotland would like to help him in his crusading aspirations, should they be free to. And it ends with a warning, that if the Pope ‘puts too much faith in the tales of the English’ then it is he, Pope John XXII, that would be judged by God for the ensuing ‘slaughter of bodies and perdition of souls and all other misfortunes that will follow’. The Declaration of Arbroath was not the first time these sentiments had been articulated to the Pope, but it was a very eloquent and powerful expression.

No, the title ‘Declaration of Arbroath’ is modern. In the centuries since it was composed, the meaning, significance and context of the document has itself has continued to evolve, as has its name. Other names by which it’s been known include the ‘Scottish declaration of independence’, as well as more descriptive titles such as the ‘letter of the barons of Scotland’. Only in the last fifty years or so has the 'Declaration of Arbroath' title eclipsed the other names by which it has been known.

The Declaration of Arbroath is a letter written to Pope John XXII in 1320 in the name of the nobility of Scotland. The letter was not written as a formal set of principles, a manifesto or as a constitutional document, though it has been seen as some of these things in the years since it was written.

A monument in Arbroath celebrates the Declaration of Arbroath. The figure on the left is Bernard, Abbot of Arbroath, with King Robert I (commonly known as Robert the Bruce) on the right. The box that Bernard wears around his neck is likely meant to be the Monymusk Reliquary, which is on display at the National Museum of Scotland. Image © David C. Weinczok

In the medieval period, the Pope was a powerful international political figure capable of arbitrating conflict and imposing sanctions. The Pope refused to recognise or address Robert I as King of Scotland, and though he urged for peace and an end to the long-running warfare between Scotland and England, he also appeared to be firmly supporting Edward II’s claim of English overlordship.

The letter set out the case for medieval Scotland to be considered as a sovereign kingdom led by Robert I drawing on historical precedent and moral arguments, and by offering the Pope both incentives and threats in an attempt to get him on side.

We know from the Pope’s reply that three letters were sent from Scotland: one from the barons, one from the King, and one from the Bishop of St Andrews. None of the letters dispatched to the Pope in Avignon survive today. The Declaration of Arbroath is a reference copy of the barons’ letter made in 1320 and kept in Scotland.

“Thus our people under their protection did indeed live in freedom and peace up to the time when that mighty prince the King of the English, Edward, the father of the one who reigns today [Edward II], when our kingdom had no head and our people harboured no malice or treachery and were then unused to wars or invasions, came in a guise of a friend and ally to harass them as an enemy.- The Declaration of Arbroath

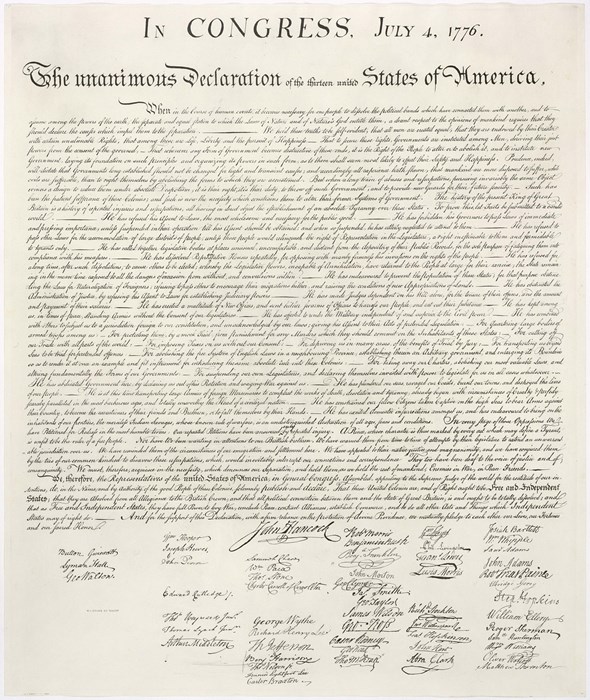

The United States Declaration of Independence, which is often and erroneously compared with the Declaration of Arbroath. Image: original: Second Continental Congress; reproduction: William Stone, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Though historians continue to research the impact of the Declaration of Arbroath on the United States’ Declaration of Independence, at present there is no evidence of a direct connection between the two documents. Indeed, the influence may run in the opposite direction, with the US Declaration perhaps influencing the popularity of the name the ‘Declaration of Arbroath’.

Regardless, the Declaration of Arbroath’s stirring language and evocative sentiments of medieval sovereign independence have given it a special distinction not just in Scotland but around the world. Many people in North America feel a particular connection to the Declaration of Arbroath and to Scotland. These sentiments are celebrated on Tartan Day, which has been held on the 6 April in recognition of the document since 1991 in Canada and 1997 in America.

To mark its 700th anniversary in 2020, we spoke to two experts to understand more about how the Declaration of Arbroath was created, and why it still resonates today.

In this podcast we are joined by National Museums Scotland's Dr Alice Blackwell, Senior Curator of Medieval Archaeology & History, and Professor Dauvit Broun, Professor of Scottish History at the University of Glasgow.

Listen to the podcast now on anchor.fm or Spotify, or in the player below:

The Declaration of Arbroath is on display at the National Museum of Scotland from 3 June – 2 July 2023. Don’t miss this rare chance to see it in person.

Find out more