Key in a search term below to search our website.

Key in a search term below to search our website.

Economic and industrial developments from the Transatlantic slave system

The Darien Scheme was set up by an overseas trading company, the Company of Scotland, created in 1695 to give Scottish merchants and investors the opportunities that their English counterparts had in the East India Company. Look closely at the coat of arms inscribed on this medal, which includes the figures of an Indigenous American and an African man. The Latin motto translates to ‘Where the world expands, its united strength is stronger’, suggesting the economic benefits that would accrue to Scotland through trade on a global scale.

Although individual Scots had taken advantage of opportunities in English-held Virginia and Dutch-controlled Suriname decades earlier, the Scheme intended to license slaving voyages and members made attempts to formally establish themselves in the slave trade system.

Between 1698 and 1700, the Company undertook an expedition to establish a Scottish colonial trading centre at Darien in Panama. Its spectacular failure, due to a combination of ill health and English and Spanish interference, resulted in the deaths of two thousand men and the collapse of the Duke of Hamilton’s plan to traffic enslaved Africans to labour in the gold mines of Panama.

Crucially, the failure led to the loss of a quarter of Scotland’s liquid capital, which hit its landed and merchant elites. This formed the background to the negotiation of the Act of Union 1707, in which Article 15 offered Scotland compensation for the Darien failure, and Article 4, the right to trade in any British port. The latter was to enable Scottish people to benefit from the spoils of colonial trade and the Transatlantic slave system.

Consider again the meaning of the motto from the perspective of the people represented on the medal. The ‘world’ certainly did not include the kind of people who would suffer the devastating loss of their land, resources, freedom and lives in a scheme intended to bring great wealth to Scotland.

Silver-gilt medal showing the Company of Scotland's coat of arms, 1700.

Silver communion cups commissioned for Kilmadock Parish Church, Doune by sugar plantation owner William Mitchell, possibly by Robert Clelland of Edinburgh, 1794.

William ‘King’ Mitchell, one of the biggest plantation owners in Jamaica, donated these cups to the church in his village of Doune in central Scotland, helping to cement a reputation of moral respectability at home.

Missionary activity was widespread across the Caribbean, aiming to replace Islam and other religions practiced there with Christianity. Closer to emancipation, many missions aimed to inculcate the ideals of what they considered to be a superior European morality and civilization. But the Christian ideals of equality and freedom at times challenged the plantation system, directly encouraging the strength and unity needed for powerful resistance or providing a cover for traditional spiritual practices.

A clear example of the outright rejection of Christianity is the famous prayer recited at the Bois Caiman ceremony that kickstarted the Haitian Revolution (1791-1804). Two of the central figures of the revolution, Dutty Boukman and Cecile Fatiman used the prayer to galvanize enslaved people in Haiti to fight for their ultimate liberation in an epic battle of good against evil.

The substantial profits made from the unpaid, forced labour of African people is said by many to have kickstarted Britain’s industrial revolution. Linen was one such industry that developed out of the Transatlantic slave system, creating thousands of new jobs and opportunities for other supporting industries across the nation. Rough, coarse linen, known as Osnaburg, was exported in huge quantities to clothe enslaved people on plantations. This heavy demand encouraged the British government to subsidise the linen industry in the mid-18th century

Attempts by the enslaved to personalise their drab outfits even in small ways were often punished by enslavers stripping the person naked and destroying the clothing in front of them. White servants were given superior quality clothing to distinguish them from the enslaved, and plantation owners and their families wore the very best quality fabrics they could afford.

Pirn winding wheel of the type used in the linen industry in Scotland in the 18th century.

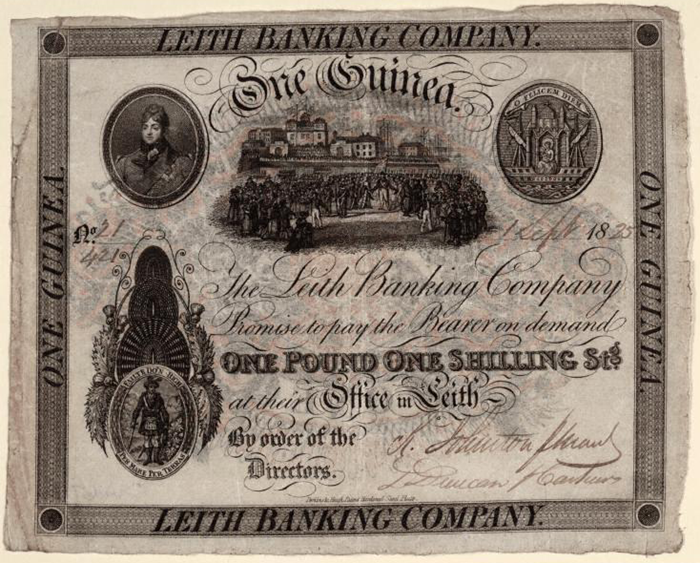

One-guinea banknote, Leith Banking Company, 1 September 1825.

In 18th-century Edinburgh, banks developed rapidly. This was aided by a strong credit system, which resulted from Leith’s position as a trading port. Scotland’s import and export trade as well as much of its industrial development had many links to the Transatlantic slave system. The Leith Banking Company was established in 1793 by 18 partners, many of whom were colonial merchants. The British Linen Bank grew out of the Edinburgh Linen Co-Partnery, an association of linen traders, to become the biggest single firm in the entire Scottish economy.

Scottish banks financed plantation owners or held mortgages for plantation properties, with enslaved men, women and children used as collateral. Often the directors of banks were enslavers themselves.

Henry Dundas was the most powerful Scottish person in the British government at the end of the 18th century. In 1792, using his influence as Home Secretary, he introduced an amendment of William Wilberforce’s bill for the immediate abolition of the slave trade, to a gradual one, to the great relief of the many plantation owners in Parliament. In 1796, the agreed compromise date for abolition, Dundas, now in the role of Secretary of State for War and the Colonies, and Prime Minister Pitt were engaged in a huge military mission to secure Jamaica and the Ceded Islands from the French, and to attempt to reinstate chattel slavery in Haiti after the formerly enslaved there had struggled to successfully emancipate themselves.

Dundas continued to oppose abolition in his later position in the House of Lords until his impeachment for embezzlement of funds in 1806. The slave trade eventually ended in 1807 with a change of government.

Portrait medallion of Henry Dundas, 1st Viscount Melville, by Tassie.

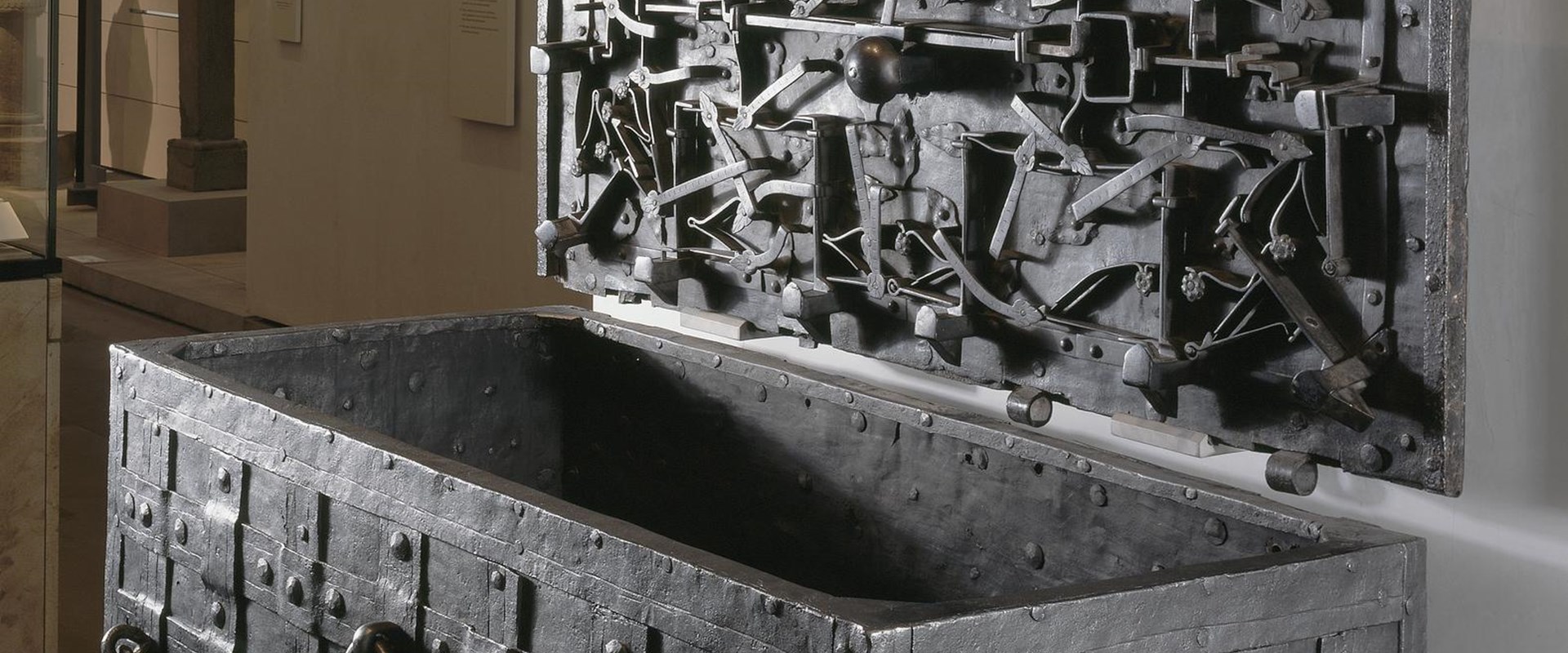

Header image: The Company of Scotland money chest, 1695.

Lisa Williams is the founder of the Edinburgh Caribbean Association, promoting the shared heritage between Scotland and the Caribbean. She is a Research Associate at the Royal Botanic Gardens Edinburgh and an Honorary Fellow in the School of History, Classics and Archaeology at the University of Edinburgh.