Key in a search term below to search our website.

Key in a search term below to search our website.

Enslavement, resistance and emancipation

British ships transported over 3 million African people between 1662 and 1807, with up to 25 % of all captive people dying on the journey. The first captive might have had to wait as long as seven months for a boat to be filled, before the two-month journey across the Atlantic Ocean.

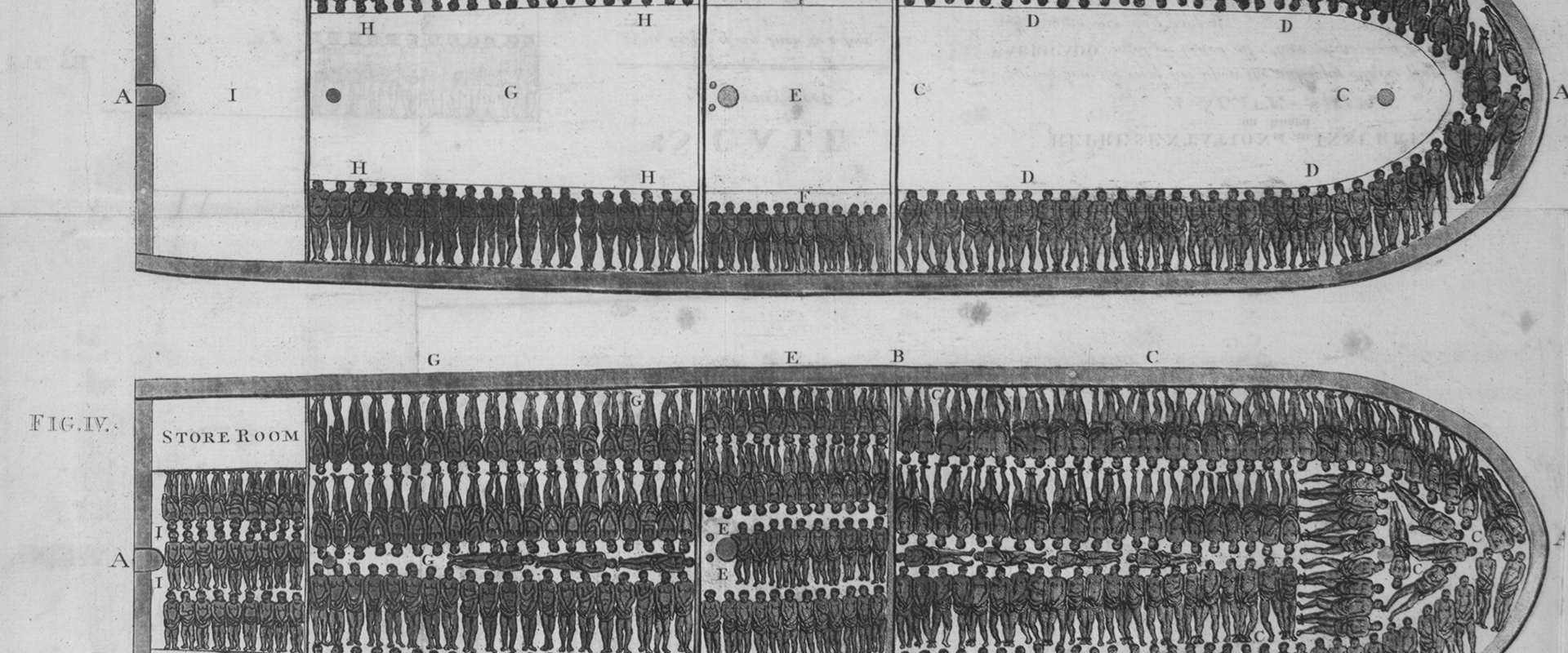

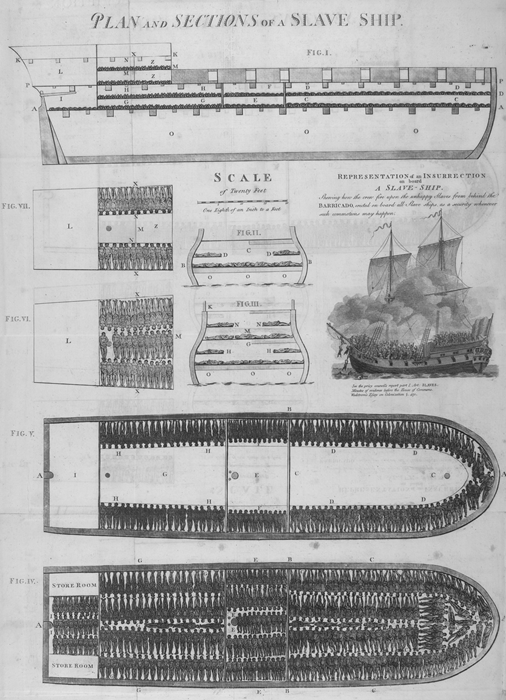

One of the most powerful images of the inhumanity of the Transatlantic slave trade, this diagram of people in the hold of a slave ship appeared on 7000 posters, distributed in 1788 as an effective propaganda tool for the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade. As the Regulated Slave Trade Act of 1788 (also known as the Dolben Act) had reduced the number of captives trafficked on a ship, the print itself shows over 100 fewer people than the Brookes would have previously carried.

The story of George Dale, enslaved in Jamaica and brought to Scotland, gives us a glimpse of the horrific experience of the Middle Passage.

Due to fear of mutiny, men were shackled, but the extra physical freedom women were given exposed them to torture, rape and unwanted pregnancy. African women and men took every opportunity to resist; from hunger strikes, suicide and infanticide to murder of the crew.

Over thirty confirmed slaving voyages left from Scottish ports, while many more Scottish ship owners, captains and surgeons took advantage of the established trade in ports such as Liverpool. The last ship to make a voyage, before the Slave Trade Act of 1807 made slave trading on British ships illegal, was the Kitty Amelia, owned by Scottish brothers George and Robert Tod from Moffat.

Plan and Sections of a Slave Ship. National Library of Scotland. CC BY 4.0

The document above shows a list of people who were sold during the sale of Huntly Estate, Demerara, previously owned by Robert Gordon of Drakies, near Inverness. Gordon had also owned Borlum estate in neighbouring Berbice, which is mentioned in the document. If you take a careful look at the list, you will notice several types of names. There are many Scottish surnames, such as Cameron and McKinnon, amongst the enslavers, but you’ll also see enslaved people listed, some with given Roman names like Scipio and Caesar and others with west African names such as Quashy and Amba.

Being sold in an auction would undoubtedly have been a highly degrading and traumatic experience; being stripped naked and intimately inspected in a public place. During auctions like these, families were often broken up and sold separately to different plantations a long distance away from each other. Songs about these heart-wrenching events are remembered today in the Caribbean. This one, lamenting parents being separated from their beloved children, is from the tiny island of Carriacou, which was heavily populated by Scottish people: listen to Maiwaz-O.

Image above: detail of a List of Enslaved Persons from Record of a Sale by Auction of Huntly Estate, Demerara, formerly belonging to Robert Gordon. National Library of Scotland.

The initials on this silver branding iron are ‘IS’ linked by a heart symbol. Perhaps they represented the name of a Scotsman, as this brand is linked to the location of St. George’s, West Indies, the capital of the island of Grenada, and it came into the Museum’s collection in 1882, via an Edinburgh auctioneer. A high percentage of Grenadian plantations were owned and run by Scottish people after the British takeover of the island in 1763 led to a frenzy of investment in highly lucrative sugar plantations.

Skin branding with a hot iron was a violent and painful experience inflicted on enslaved men, women and children on a slave ship or when they were sold in the Americas. Just as scarification would have been a way of marking belonging to a culture and community, branding did the opposite. As part of the dehumanising process, losing your individual identity marked the transition from being considered a human being to a commodity that could be traded in the chattel slavery system and who had no right to life.

Silver brand said to have been a brand for marking enslaved people, from St George, West Indies.

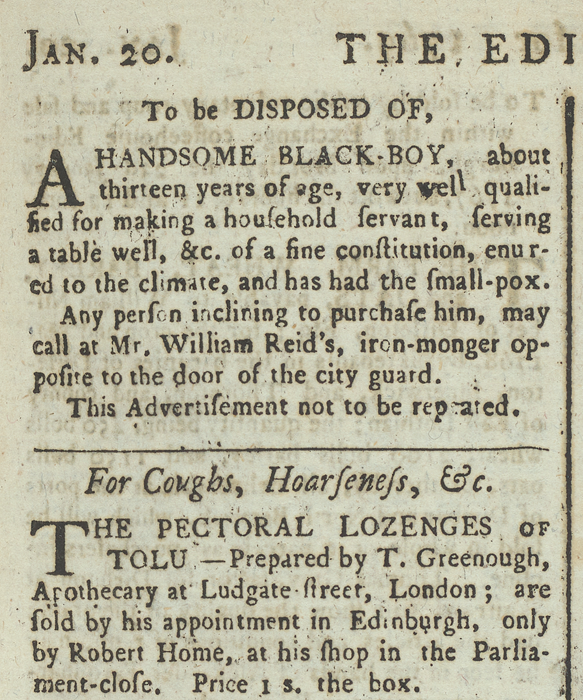

Edinburgh Advertiser 20 January 1769. National Library of Scotland. CC BY 4.0

Advertisements like this often appeared in Scottish newspapers for both the sale of enslaved people, generally children, and for the return of so-called ‘runaway slaves’, often young men in their teens and early twenties. Note the casual cruelty of the phrase ‘To be disposed of’, referring to the fate of a thirteen-year-old house servant assumed to be someone’s property. The word ‘Handsome’ alerts us to the fact that children who were trafficked to Scotland from the colonies were often dressed elaborately and used as exotic status symbols.

After arrival in Scotland, several brave men, who had been formerly enslaved in the colonies, challenged the legality of slavery in the Scottish courts. Famously, in 1778, after his legal marriage to a white Scottish woman, Jamaican servant Joseph Knight won his case against enslaver John Wedderburn, and as a result, those once considered to be enslaved in Scotland were finally and unambiguously protected as free people under Scottish law. Henry Dundas was one of Knight’s legal advocates, yet this ruling did nothing to change the situation of enslaved people in the Caribbean.

During centuries of enslavement, an ongoing war of resistance erupted almost every year across the Caribbean and South America, from Jamaica to Guyana, increasing in urgency in the years leading up to emancipation. Mountainous and deeply forested areas provided safe cover for maroons (formerly enslaved people who liberated themselves from plantations) and a base for guerrilla warfare, which struck fear into those upholding the slave labour system.

Scottish enslavers, governors and military leaders retaliated in the worst of ways: mass starvation of the Garifuna people in St Vincent; the release of murderous bloodhounds onto the resisting maroons of Jamaica; and the slow public torture and execution of leaders and suspects.

In Haiti, building on these earlier resistance movements, substantial maroon communities and the unifying effect of African spiritual ceremonies, Toussaint L’Ouverture led a full-scale revolution, which by 1803 had overthrown slavery and defeated British, French and Spanish armies. This sent shockwaves throughout Europe and inspired wider resistance for decades to come.

The Haitian constitution of 1806 went further than any other in the world, ensuring that human rights and equality for all were inscribed in law, and Haiti became the first free Black republic in the world. Liberation movements and heroes such as Queen Nanny of Jamaica, Joseph Chatoyer of St Vincent and Quamina Gladstone are commemorated and celebrated across the Caribbean to this day.

Toussaint L’Ouverture © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Header image: Plan and Sections of a Slave Ship. National Library of Scotland. CC BY 4.0

Lisa Williams is the founder of the Edinburgh Caribbean Association, promoting the shared heritage between Scotland and the Caribbean. She is a Research Associate at the Royal Botanic Gardens Edinburgh and an Honorary Fellow in the School of History, Classics and Archaeology at the University of Edinburgh.