Key in a search term below to search our website.

Key in a search term below to search our website.

James Clerk Maxwell used these disks during his research into colour vision, to establish how people see mixtures of colours.

Date

1855

Made from

Metal, paper

Made by

James Mackay Bryson of Edinburgh (1824-94)

Museum reference

On display

Enquire, Level 5, National Museum of Scotland

James Clerk Maxwell’s interest in colour vision started when he was a young man. He was introduced to the topic when he was 18, by one of his professors at the University of Edinburgh, James Forbes. Maxwell went on to study at the University of Cambridge, and while there carried out research into colour vision, and specifically into how people see mixtures of colours. If two colours are mixed, do we all see the same result?

Above: James Clerk Maxwell with his first design of colour top, 1850s. Original at Trinity College, Cambridge.

The apparatus which he used at first for this research was a colour top. He had been introduced to these by Forbes and was photographed holding this first top as a young man, which shows the importance he attached to it. This top itself survives in the collections of the Cavendish Laboratory in Cambridge.

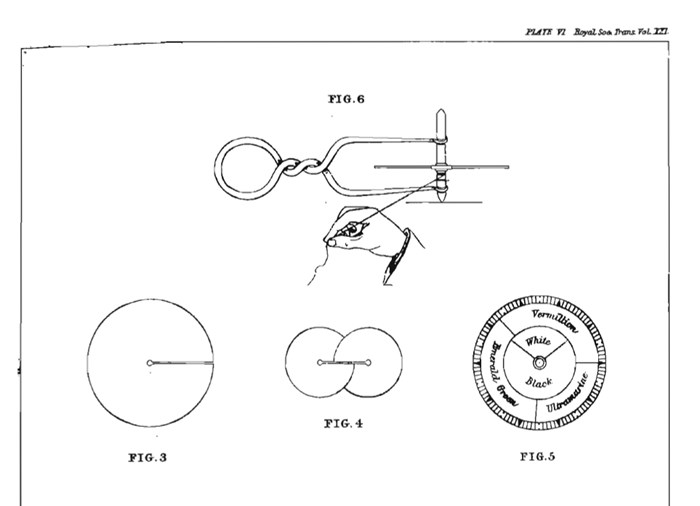

Maxwell soon invented a smaller top (which was probably easier to spin fast) and was made for him by the optical instrument maker Bryson of Edinburgh. This consisted of a metal disk with a scale around its edge which was divided into 100, paper disks of two sizes painted with artists pigments (named on their backs) and an axle which held the whole together and allowed it to spin.

Above: Maxwell’s diagram of the spinning top and disks. Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, 1855.

To use a colour top, two or three of the larger disks are selected and slotted together so that part of each shows. These are placed on the top and the percentage of each colour visible was read off the outer scale. The disks aren’t perfectly round; each one has a small tab sticking out to help read the scale. Two or three of the smaller disks were slotted together and placed on top, leaving the larger disks visible as a ring.

When the top is rapidly spun, faster than the eye can follow, the colours seem to blur together. Two colours are seen, one in the outer ring, and one in the centre. If the disks have been correctly chosen, and the proportions of different colours carefully adjusted, both the outer ring and the inner circle can appear the same colour when the top is spun.

This is what Maxwell did, carefully recording the different colours and proportions necessary to get the inner and outer colours to match. He found that the proportions of colours which were seen as the best match depended slightly on the observer, and a few people who were colour blind gave very different answers. The results also changed according to the light source; most of his readings were taken in sunlight, but some different results were obtained looking at the top under (Edinburgh) gaslight. The exact colour of gaslight varied because of differences in local supply and contaminants in the gas, and also would have depended on burner design.

Above: Professor Forbes’ set of Maxwell’s disks. He would have had more colours which do not survive.

Being one of Maxwell’s observers must have been a fairly long and likely tedious task. It required staring repeatedly at the spinning top (or at the light box Maxwell also used) and describing the difference between the two colours. In 1859 he wrote to his childhood friend, the physicist Peter Guthrie Tait:

“I have got a good specimen of colour blindness in my class. I experimented on him yesterday. He is absent today I hope not in fear of the top.- James Clerk Maxwell, 1859

Maxwell’s 1860 paper on colour vision featured two main observers ‘J’ and ‘K’. ‘J’ was James Clerk Maxwell himself, and it is clear from contemporary letters that the anonymous ‘K’ was his wife Katherine, who collaborated with him on experiments both before and after their marriage.

Three examples of this top are in the National Museums collection, without their axles. One had belonged to James Forbes, who started Maxwell’s interest in colour vision, another to Edinburgh University and the coloured disks of the third were discovered tucked into the drawers of an earlier piece of apparatus, a predecessor of Maxwell’s top made in about 1830.

Above: Optical photometer for the measurement of the intensity of light and colour, to the design of the photographic pioneer William Henry Fox Talbot, constructed by W. & S. Jones, London, c. 1830 with Maxwell’s disks shown to the back right.

Another Edinburgh academic very interested in colour blindness was George Wilson, the founding Director of the Industrial Museum of Scotland, now the National Museum of Scotland. He published in 1855 what is acknowledged as the first book on colour blindness, including concern for the safety of coloured signals. (Why, he asks, are signal lights red and green, when those are the colours confused in the most common form of colour blindness?) He also corresponded with Maxwell, and reprinted Maxwell’s research as an appendix to this book.

In 1855 Maxwell’s research into colour vision led him to suggest how to take a photograph that would appear to be fully coloured, using three black and white slides and three coloured filters. In 1861 he commissioned Thomas Sutton to take a demonstration photograph of a tartan ribbon which he showed projected onto a screen at King’s College London. This image shouldn’t have worked as well as it did, because the photographic chemicals did not respond to red light. Serendipitously, unseen ultraviolet light also reflected off the red portions of the ribbon and provided the third colour.

Above: Demonstration peacock feather, Sangar Shepherd & Co, c1905.

The first colour photographs used a technique suggested in 1855 by James Clerk Maxwell. Three separate images were taken in three different colours and projected onto the same surface, or, as here, viewed stacked up.

A few of these disks are on display in the Enquire gallery, and also a larger working version of the apparatus showing the colour mixing in action.