Key in a search term below to search our website.

Key in a search term below to search our website.

“The first time I saw them was completely surreal. Holding an exact replica of your brain sounds like something from a science fiction novel but it was an incredible experience.- John Scott, Lothian Birth Cohort participant

What is it?

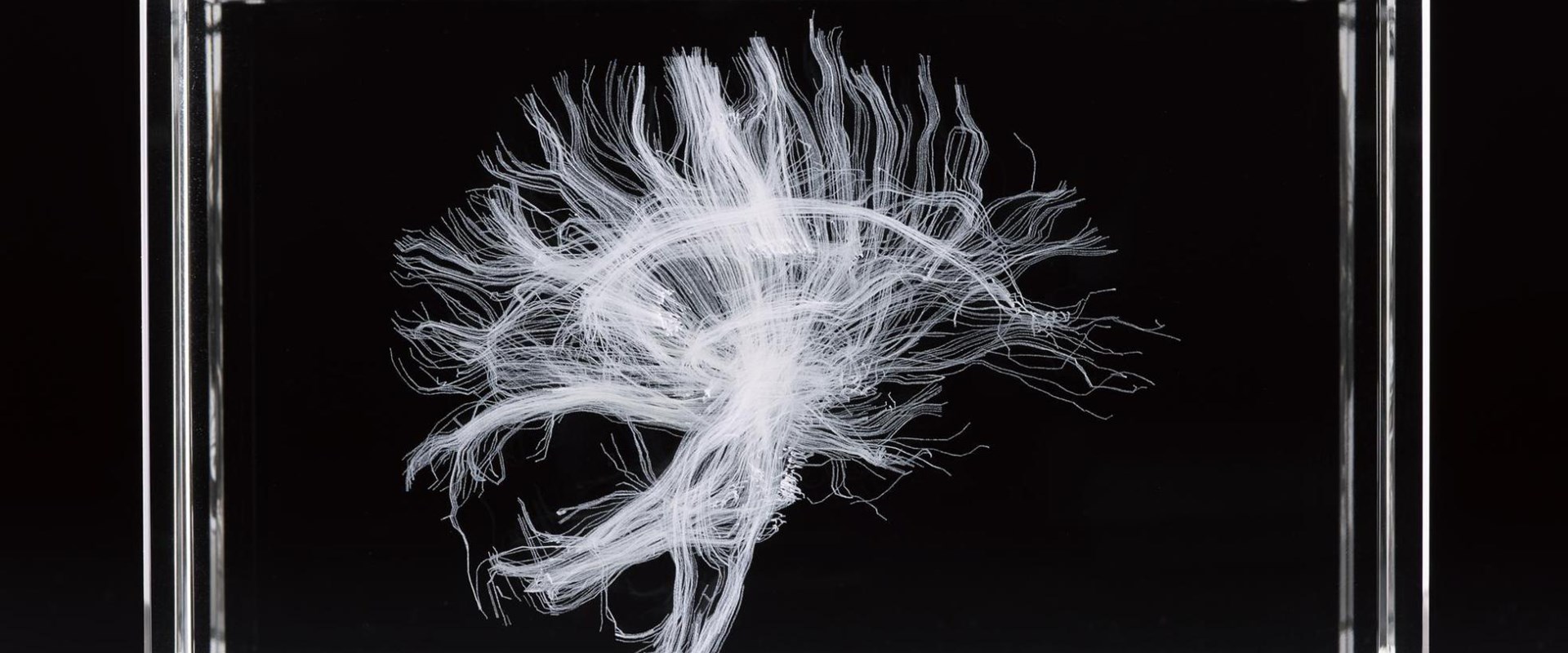

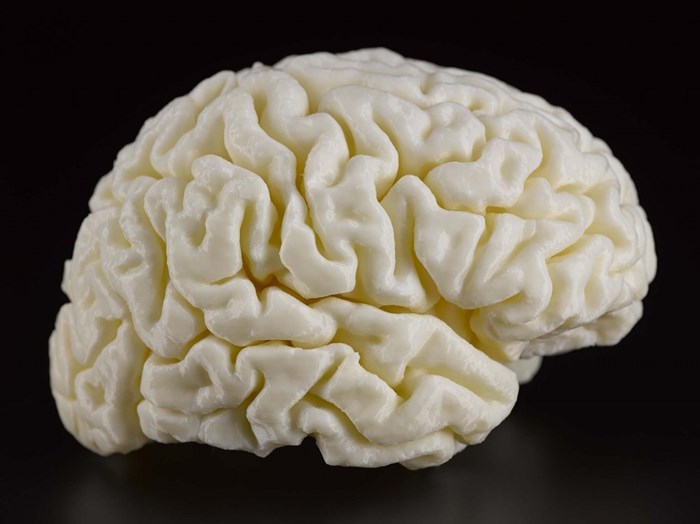

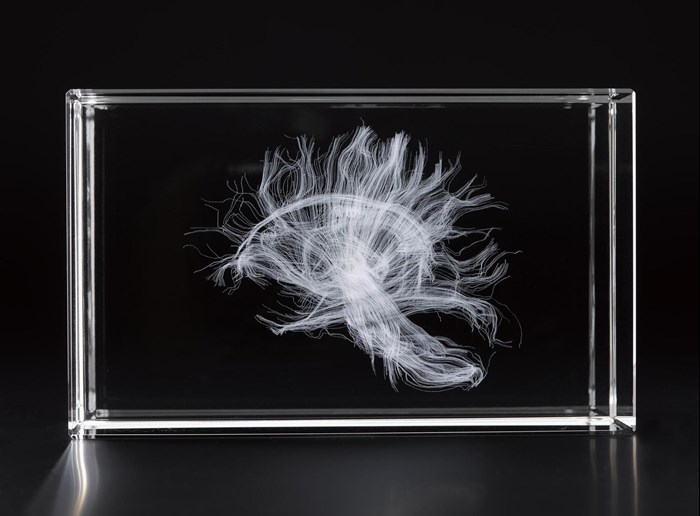

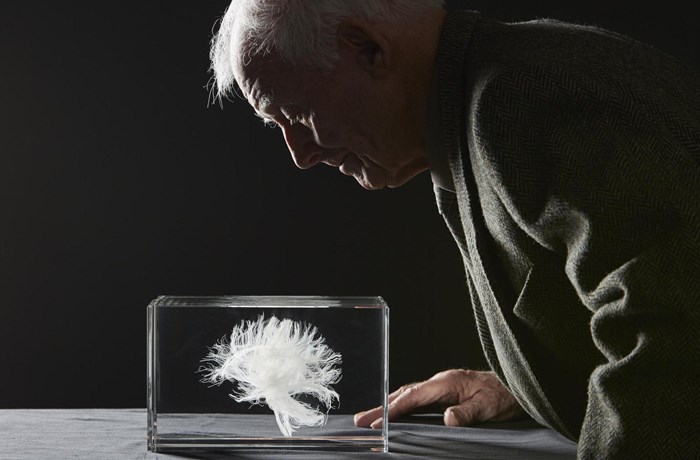

There are three objects representing the Lothian Birth Cohort on display. The first is a laser-etched crystal of the neural connections in John Scott’s brain. Extensive MRI scans also helped us to create a 3D-printed model of John's brain, which he was then photographed with.

Date

2016

Made by

Edinburgh Imaging, the University of Edinburgh and National Museums Scotland

Museum Reference

On display

Enquire, Level 5, National Museum of Scotland

Did you know?

These unique models revealing the inner workings of John’s brain follow almost seven decades of research.

Scotland is home to the longest study of human cognition in the world. Known as the Lothian Birth Cohort, the story of this ongoing study at the University of Edinburgh is told with medical imaging in our new Enquire gallery.

Over the last year we have worked with the University to identify a participant who would be happy to go ‘on display’. John Scott, a retired miner from Tranent, gamely volunteered and extensive scans of his brain were used to produce three objects for display.

All children in Scotland who were born in 1921 or 1936, and attending school in the June of 1932 or 1947, took an intelligence test called the Scottish Mental Survey. The Survey was originally given to find out the average intelligence of all children in Scotland. From records, the results of these tests and their participants have been traced and retested: they are the Lothian Birth Cohort.

A group of 11-year-old schoolchildren on the first year they took the test. Our participant, John Scott, is in the centre of the front row.

The original tests have provided a baseline which researchers have used to study ageing and the brain. These further studies have yielded a fantastic amount of research and have been widely covered in the media, producing headlines such as ‘Bilingualism has a positive effect on cognition in later life’ and ‘Cigarette smoking and thinning of the brain’s cortex’.

John doesn’t remember taking the initial test as a child. But he and the rest of the 1936 Cohort turn 80 this year, and with each passing year of study we learn more and more about ageing and the brain.

As a part of the research undertaken for the Cohort, participants have been scanned extensively. It's these scans that we've used to create three new objects for display.

The first is a 3D-printed model of John’s brain.

The second is a laser-etched model in crystal of the white matter, or neural connections, in John’s brain. This has been printed in two halves and is very interesting because his brain stem is off-centre!

The third object is a photograph of John holding his brain and white matter, taken earlier this year at our Collections Centre in Edinburgh. John hadn’t seen either of the models before his visit to the Centre and he “hadn’t realised all that was going on up here.”

I was one of 70,805 children given the Scottish Mental Survey, which analysed the average intelligence of schoolchildren born in 1936.

As my 70th birthday approached, myself and 1,000 others from the initial tests were recruited by the Centre for Cognitive Ageing and Cognitive Epidemiology at the University of Edinburgh to take part in a follow-up study, the Lothian Birth Cohort 1936.

The physical health and cognitive skills of each participant were tested every three years over a decade. The results formed the foundations of the world’s largest study into how childhood mental capacity affects health and cognitive function in later life.

I can’t quite remember taking the survey all those years ago but when the University of Edinburgh got in touch, I was more than happy to get involved.

I went through health examinations and MRI scans, and sat a test similar to the one from my school days. As a miner born and raised in Tranent, East Lothian, I was used to lying in confined spaces, so the lengthy scans never bothered me.

Data from the scans was used to create a 3D replica of my brain and a laser-etched model in crystal of my white matter.

The first time I saw them was completely surreal. Holding an exact replica of your brain sounds like something from a science fiction novel but it was an incredible experience. The crystal model is printed in two halves and if you look closely enough, you can see my brainstem is off-centre.

When my youngest grandchild saw me on the telly she said, “Granda, I saw your brain on the television. Was it sore getting it out?” I told her it wasn’t too bad. I’m proud to have taken part in a project that will help others.