Key in a search term below to search our website.

Key in a search term below to search our website.

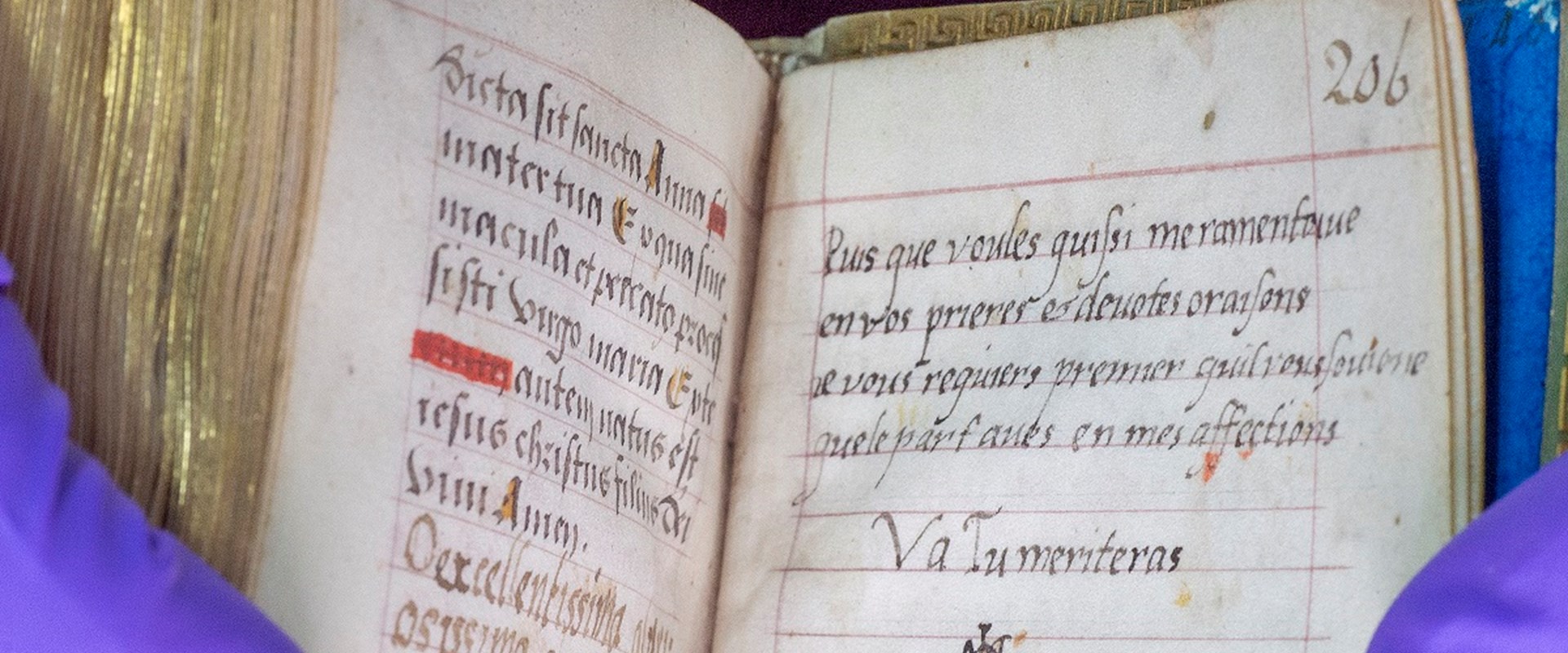

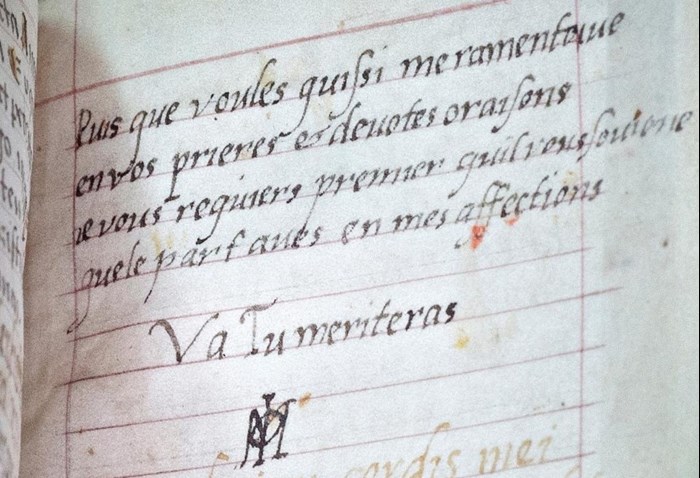

Written in the late 1550s in the teenage Mary’s finest script, the inscription is a witness to a conversation between the young queen and her great-aunt, Louise de Bourbon, Abbess of the royal abbey of Fontevraud. In it, she asks the Abbess to remember the love that Mary has for her, when in turn the Abbess remembers Mary in her prayers.

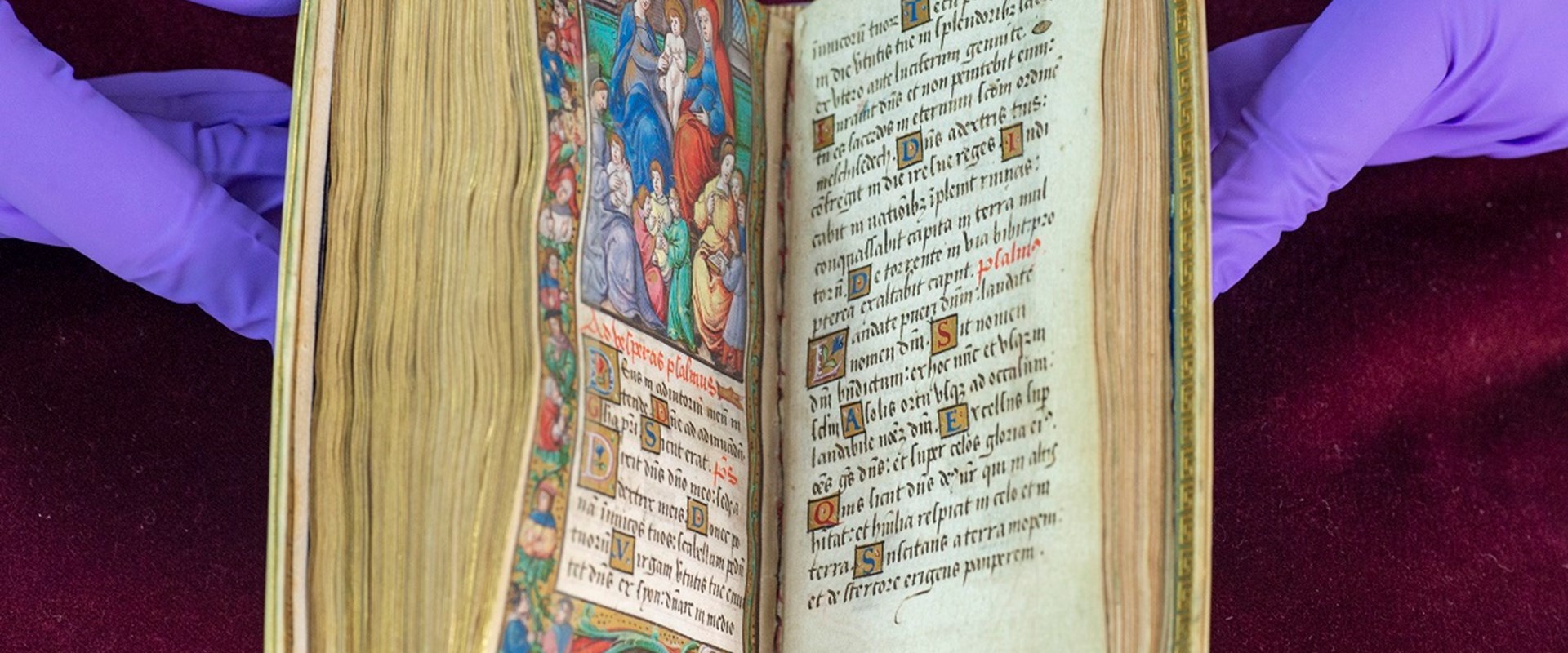

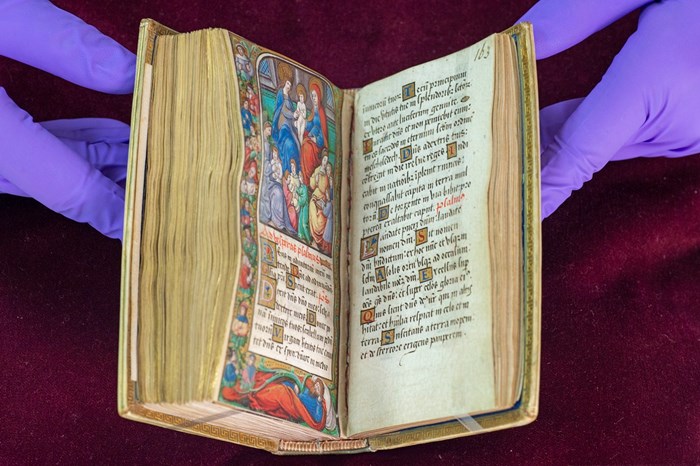

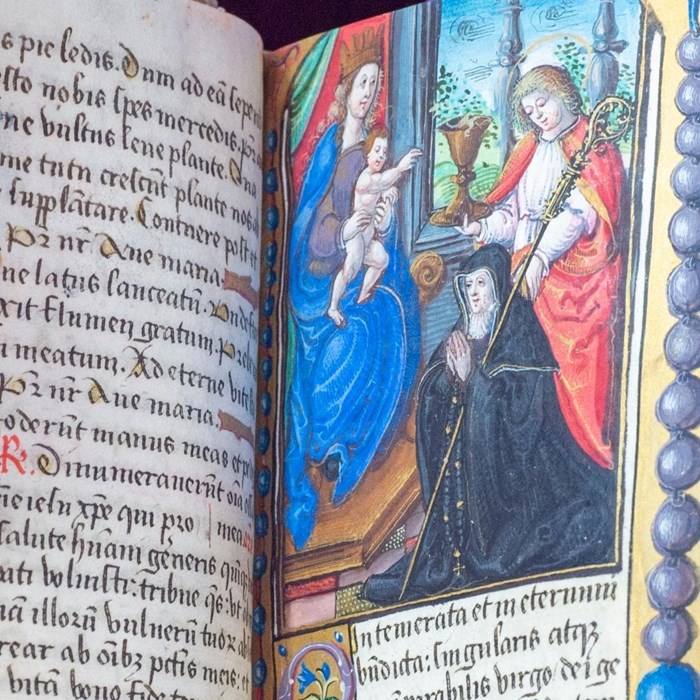

The verse sits within a manuscript 'Book of Hours', a collection of prayers and psalms written in Latin. Probably made in the 1530s, it contains forty exquisite illuminations on 200 leaves of vellum. It is believed that the Abbess gave this precious volume to Mary around the time of the Scottish queen’s marriage in 1558 to the heir to the French throne, the Dauphin François.

One of the 40 illuminated pages of the Book of Hours. © Neil Hanna

Mary had been brought up at the French court since 1548 when, aged six, she was removed from Scotland amid fears for her safety during the Anglo-Scottish wars of the Rough Wooing. Her mother, Marie de Guise, remained behind in Scotland, so Mary was particularly dependent in France on her powerful French relations, like the Abbess Louise. The verse is a touching tribute to that relationship.

Mary was a devout Catholic during a period of Protestant Reformations throughout northern Europe. The Book of Hours would have been used for private prayer, containing religious texts for certain times in the day – Matins, Vespers and so on - and in the ecclesiastical calendar.

See the inscription and other highlights from the Book of Hours in our video presented by Dr Anna Groundwater, Principal Curator of Renaissance and Early Modern History.

The very fine illuminations were created by a ‘Master’ artist, with connections to the royal court, who worked for the Archbishop of Lyon, François de Rohan. This artistry makes the prayerbook a valuable object, and as such, it was not simply a tool for prayer, but a sign of exclusivity, of status for the person who commissioned it, the Abbess, and those that then owned it.

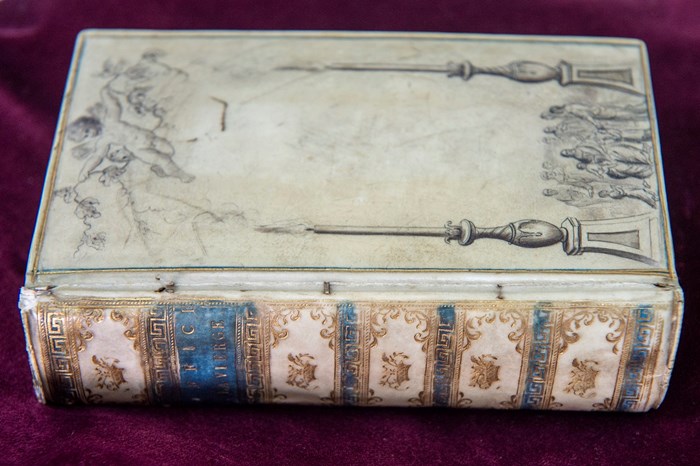

But more than this, the survival of this particular Book of Hours for nearly 500 years, and in such remarkably good condition, is compelling evidence of the reverence in which its subsequent owners have held it, thanks to the words of the young Queen of Scots. Mary’s verse has kept this precious book treasured, protected and preserved, as a relic of Scotland’s most famous queen.

Spine and cover of the Book of Hours. © Neil Hanna

Use the viewing tool below to get up close to every detail in a selection of six illuminated pages in the Book of Hours.

Want more detail?

Explore the full 400 page with our interactive viewer (link opens in new window)

We can imagine the painstaking care with which the teenage Mary will have inscribed her words in such a valuable work of art, keeping to the ruled lines.

Following the Latin quatrain, Mary adds a motto, ‘Va tu meriteras’, translated as ‘Go, thou shalt merit’. She then signs it with a monogram combining her ‘M’, and the Greek letter Φ, the phonetic representation of ‘F’ for François.

Combined, the inscription and signature communicate her affection for two of the people closest to her in France, her new young husband François, and her great-aunt Louise.

Transcribed into English, Mary's verse reads:

Since you wish to remember me here

in your prayers and devout orations,

I ask you first that you remember

what part you have in my affections.

Mary, Queen of Scots' four-line verse in Latin. © Neil Hanna

Mary, Queen of Scots by François Clouet. Royal Collection of the United Kingdom, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Louise de Bourbon was one of a number of Mary’s powerful de Bourbon and de Guise relations, which included several prominent women like Louise’s sister, and Mary’s grandmother, the formidable Antoinette de Bourbon, Duchesse de Guise. The composition by Mary in French to her beloved great-aunt in the late 1550s is testament to the young queen’s position within that influential circle.

In 1559, Mary, Queen of Scots, became Queen of France too on the death of her father-in-law Henri II, and the accession of François as François II. This was Mary at the peak of her powers, the young, beautiful queen of one of the most sophisticated European courts, her monarchical skills refined in the forge of its political chicanery. She was multi-lingual, and educated in the arts of rhetoric and diplomacy, as well as the more feminine pursuits of song, dance and embroidery.

But this deceptively simply verse, composed by the teenage queen, suggests something more: this was Mary the accomplished poet, packing more meaning into its four lines than is perhaps immediately apparent.

At the same time, the endearing combination of her initial M with that of François, suggests a youthful expression of the unusually affectionate relationship between this royal couple.

The Book of Hours was on display at the National Museum of Scotland thanks to a generous loan by its new owner, Count Peter Pininski.

For several hundred years the book was in the hands of the Hale family of Alderley, Gloucestershire. This family was in possession of papers relating to Mary, Queen of Scots, which had come to them via the antiquary John Selden in the 17th century. Selden had acquired them from the family of Henry Grey, 6th Earl of Kent, an official present at Mary’s execution at Fotheringhay Castle, Northamptonshire, in 1587.

Louise de Bourbon, Abbess of Fontevraud, being presented by St John to the Virgin Mary and child. St John holds a chalice from which a tiny demon is emerging (f.18). © Neil Hanna