Key in a search term below to search our website.

Key in a search term below to search our website.

The Roman invasions of Scotland left behind many extraordinary archaeological finds now on display in the National Museum of Scotland. Whether due to their craftsmanship, insights into life on the frontier, or potential to evoke awe, these five objects are a dramatic starting point for understanding the Romans in Scotland.

This magnificent sheet bronze mask was once attached to the parade helmet of a Roman cavalry trooper. Helmets like this were worn for dramatic effect during exercises rather than on the battlefield, as the mask would restrict the wearer's vision too much for effective combat use.

In these shows, which were part of a soldier’s training, troopers took on the roles of mythical figures. This mask shows a youthful female face with an elaborate hairstyle and probably represented an Amazon, a warrior woman mentioned in Greek myths. Only the most skillful soldiers had helmets like this.

This helmet comes from Trimontium, the Roman fort near Newstead in the Scottish Borders. It is one of three which were found at the site, which together form one of the finest groups of such helmets from anywhere in the Roman world.

Bronze face mask, from the Roman site at Newstead, late 1st century AD (X.FRA 123).

Bronze face mask, from the Roman site at Newstead, late 1st century AD (X.FRA 123).

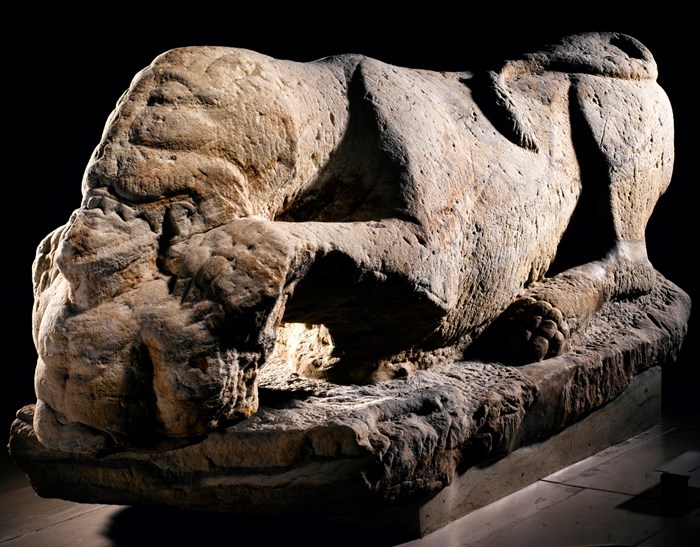

The sandstone lioness from Cramond, just west of Edinburgh, is a rather terrifying piece of Roman sculpture. This near-life-sized big cat has pounced on her prey, a naked, bearded man. The body of the lioness shows great attention to detail but the head end is exaggerated, with her mouth distorted to fit even more teeth in. The lioness turns into a monster.

This macabre sculpture is a version of a typical Roman motif: the idea of a dangerous beast and its prey. It symbolised the power of death, and would originally have stood on a grand tomb, guarding the inhabitant and reminding the onlooker of the inevitability of death.

The roughly life-sized Cramond lioness in full (X.1997.6).

The roughly life-sized Cramond lioness in full (X.1997.6).

However, the message was not entirely morbid. To either side of the plinth, snakes are carved. In Roman beliefs these symbolised the survival of the soul, suggesting that the dead person was now in a happier afterlife.

The man trapped by the lioness is a key part of the story. The angle of his arms shows that his hands were tied behind his back. He was a captive and he represents a local opponent of Rome: a barbarian in Roman eyes, similar to the ones shown on the Bridgeness slab. This sculpture was a victory monument as well as a tomb guardian.

The lioness was found in the river Almond, just below the Roman fort of Cramond. Originally, she must have been placed on a grand tomb facing the unconquered lands to the north. The men who built this tomb thought Rome was here to stay and built a monument for eternity. However, just a few short years later, the fort was abandoned and the tomb was carefully dismantled, with the lioness consigned to a watery grave.

After the better part of 2,000 years, the Cramond lioness was found in the mud at the mouth of the river in 1997 by ferryman Robert Graham. It was excavated and lifted by a team from City of Edinburgh Archaeology and National Museums Scotland. After a lengthy conservation process to remove damaging salts from its long immersion in seawater, it was acquired jointly by National Museums Scotland and Museums & Galleries Edinburgh.

In nearby Cramond Kirkyard are the remains of the Roman fort. A Roman shrine with a carving of a standing god in a niche (often, but incorrectly, known as ‘Eagle Rock’) can be found along the shoreline on the other side of the river.

Front view of the ferocious lioness, spotlighting the captive being devoured.

Front view of the ferocious lioness, spotlighting the captive being devoured.

The rocky outcrop popularly known as 'Eagle Rock' along the Cramond shoreline. © David C. Weinczok

The rocky outcrop popularly known as 'Eagle Rock' along the Cramond shoreline. © David C. Weinczok

This leather chamfron is a horse’s headdress. It would decorate and protect the animal in parades, training and battle. The thick, decorated outer layer of cow skin is lined with supple, soft goat skin. Small holes along the edge held a cloth or leather binding and fastening straps.

The chamfron was highly decorated, although only traces survive. Between the two eye holes, small brass studs mark out a circle and a line of arcades. Originally this circle would have held a decorative brass figure or ornament. The rest of the surface is covered in vine-leaf decoration. Again, only the studs on the edges remain, but originally there would have been decorative brass sheets. A single circular one survives near the top left edge. Below the eyes, a rectangular tablet with triangular lugs originally held an inscribed plaque with the owner’s name or unit.

Replica of leather chamfron, horse's headpiece with globular bronze eye-guards, from the Roman site at Newstead, late 1st century (X.1997.272).

The original chamfron (X.FRA 74).

Replica chamfron based on the original from Newstead (X.1997.272).

Chamfrons are rare and would have been worn only by the horses of high-ranking cavalrymen. The narrow gap between the eyes suggests this one was intended for a slender, graceful beast.

Leather rarely survives after two thousand years of burial, but our example had been dumped in an old well at the Roman fort of Trimontium (Newstead) around AD 100. The waterlogged conditions preserved the leather perfectly, and the remaining brass fittings were still as shiny as the day it was buried, though most of the brass had been stripped off it before it was discarded.

This spectacular mass of silver, weighing over 23kg, is the biggest hoard of Roman hacksilver (crushed and chopped-up silver) from anywhere in the Roman world. Hacksilver seems a strange idea: why would you deliberately damage beautiful and expensive vessels?

This hoard was found on a hillfort at Traprain Law, which lay beyond the edge of the Roman Empire when the silver was buried in the early fifth century AD. When it was discovered, archaeologists thought it was loot from raids on the Roman world, with the raiders dividing the spoils.

However, recent research suggests a different story. Evidence shows that the silver was originally cut up quite carefully to standard sizes and weights. It represents bullion, which is a way of trading in precious metals using set weights. This silver came north from the Romans to their allies, either as a diplomatic gift or as payment for military service. The powerful people on Traprain Law had long been friends of the Roman world.

Most of the silver originally came from fine dining services which would have graced the tables of the Roman elite. There are remains of huge platters for serving food, and smaller bowls and plates for individual portions. Other silver items were used for bathing and personal hygiene. Fluted basins once held water for washing, while well-polished mirrors helped to fashion your appearance. They are reminders of the luxurious lifestyle of high-status Romans.

When the silver came to Traprain it served a very different elite lifestyle. No longer gracing fine feasts, it was valued as raw material. This silver was a treasury, a source of wealth that could be given to other tribes to build alliances or melted down and used to make local power symbols. One of these, a magnificent silver chain, was found on Traprain Law itself. It seems some of the Roman silver had already been consigned to the melting pot.

Silver wine strainer with 'Chi Rho' and ‘Iesus Christvs' perforated on the bowl, from Traprain Law, AD 410 - 425 (X.GVA 111).

Belt fittings with surviving leather; brooch; and twisted pin, from Traprain Law, East Lothian, AD 410 - 425 (X.GVA 145-151).

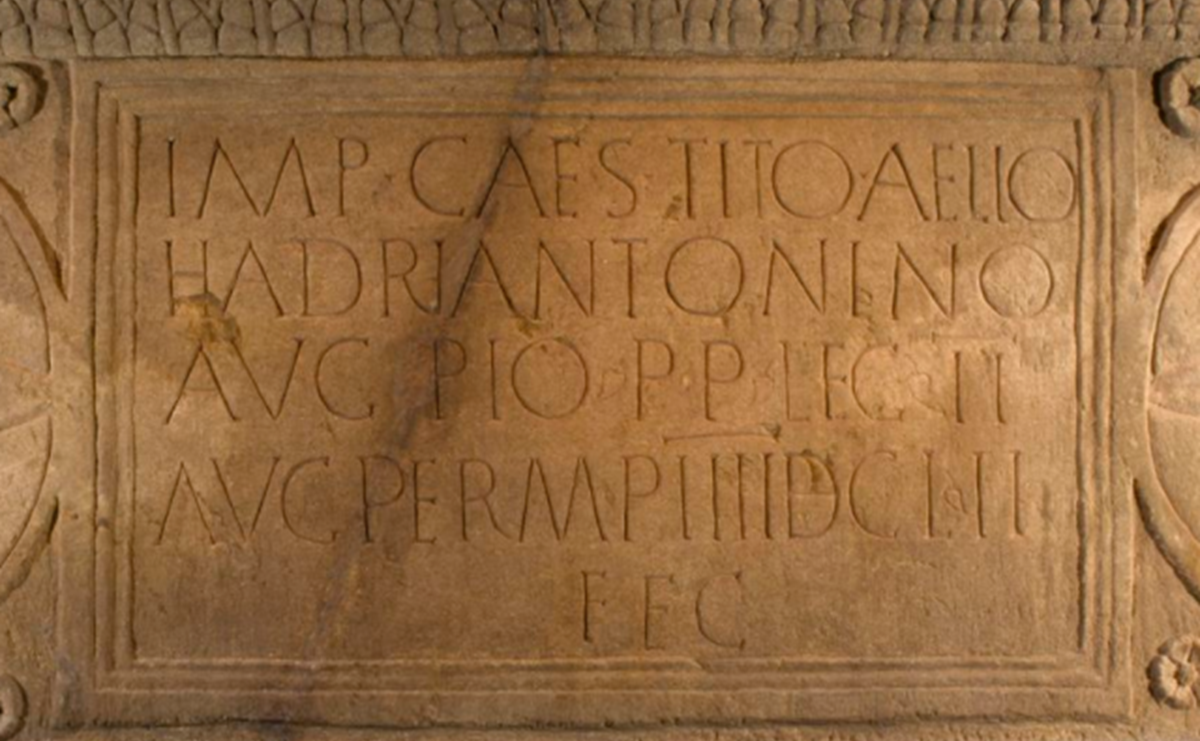

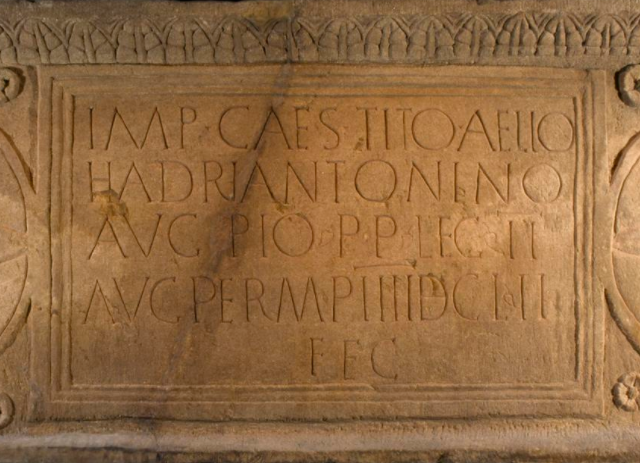

When the Romans reoccupied southern Scotland in the mid-second century AD, they built the Antonine Wall across the narrowest bit of country, from Forth to Clyde. The working parties commemorated this monumental effort by erecting stone slabs at the end of the stretches they built. To mark the eastern end of the wall, in the area of Bridgeness (part of modern Bo’ness), the most spectacular slab was erected.

The Bridgeness slab was a sculpture on a grand scale. The carefully carved inscription, originally picked out in red paint, dedicated the building of this stretch of the Antonine Wall by the Second Legion Augusta to the emperor. On the right is a religious scene, with the legion’s commander pouring an offering on an altar. Three animals are about to be sacrificed to the war-god Mars.

The inscription names the emperor, Antoninus Pius, with his full official titles and honours. The remainder commemorated the legion that built this part of the wall, the Second Legion Augusta (X.FV 27).

The left-hand scene is pure propaganda. It shows a Roman cavalryman riding down his enemies. They are depicted as naked, defeated, captured and executed. It is, of course, a very one-sided view, created by the victors. Archaeological evidence allows us to tell a more complex story of this relationship.

The left-hand picture propagandises the Roman conquest. A Roman officer on horseback is riding down four local warriors depicted as nude and fleeing, reinforcing the contrast between 'civilised' Romans and their 'savage' foes.

The right-hand panel shows a religious ceremony. Three animals (a pig, a ram and a bull) were sacrificed to the war-god Mars to purify and prepare the army for the task of conquest and construction.